Thought wolverines were “endangered”? Officially, they aren’t. That status may change

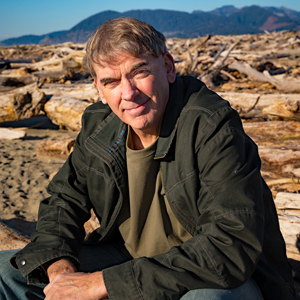

Waiting on a friend: This juvenile male wolverine in Washington’s South Cascades could use some protection. Photo: Kayla Shively

By Jordan Rane, June 13, 2022. So sparse these days they’re about as mythical as the Marvel Comics creature, American wolverines received rare federal support with a recent court order telling the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service it must reevaluate the animal’s status for inclusion under the Endangered Species Act.

It’s not the first time ESA protection has been considered for the elusive, weasel-related mustelid—a snow-dependent species with legendary grit that once thrived across the Columbia River Basin before being nearly wiped out by pelt hunters and residual habitat loss.

A decade ago, Fish and Wildlife planned to list wolverines as “threatened.” It reversed that decision in 2020.

The reversal led to a lawsuit from the Center for Biological Diversity, Idaho Conservation League and other conservation groups. Late last month, Montana U.S. District Court Judge Donald W. Molloy ordered the agency to submit a new final decision regarding wolverine protection within 18 months.

“We’re very happy about this decision—and hopeful,” says Jocelyn Akins, founder of the Cascades Carnivore Project, who has written about her extensive fieldwork with wolverines in a previous Columbia Insight article. “The science is about as strong as it gets that they’re in need of listing and protection.”

MORE: Wolverines break through … finally!

What’s kept wolverines off the ESA list to date—and, instead, on what conservationists have described as a “roller coaster of litigation” with federal wildlife authorities?

“I don’t know how to answer that because it really has nothing to do with the actual findings of scientists and wolverine experts—and everything to do with strange politics and lobbying groups that know nothing about wolverine conservation but have weighed in heavily on these decisions nonetheless,” says Akins. “At this point, it’s really a matter of the high-ups at the Fish and Wildlife Service doing the right thing.”

“Farm bureaus, snowmobile associations and the American Petroleum Institute, the main oil industry lobbying group, have … argued against listing wolverines as threatened or endangered,” according to a 2020 New York Times article.

How many wolverines?

“Wolverines are clearly threatened,” says Akins. “We’re talking incredibly low numbers here.”

An estimated 300 wolverines remain in the Pacific Northwestern states outside of Alaska—most of them in the mountains of northern Idaho and Montana.

There are currently about 50 wolverines in Washington.

Maybe closer to 40, says Akins.

Or 39.

“A wolverine was shot in Centerville, Wash., a couple weeks ago—in a chicken coop,” says Akins. “It was roaming into the shrub-steppe and got in trouble.”

MORE: Second family of wolverines documented at Mount Rainier National Park

Dependent on snow for reproduction and nesting, as well as physiologically (to prevent overheating), wolverines are facing additional stress and habitat loss due to lighter snowpacks and warmer climates.

While females have smaller territorial ranges, studies have shown that lone males can routinely cover 600 square miles or more—and provide states that once had healthy wolverine populations with just a single hardy resident with little hope of growth.

“There’s one wolverine in California, one in Oregon, one in Colorado and one in Utah,” says Akins, adding that each has a name.

Oregon’s lone wolverine resident is Stormy. He’s been in the state since 2011.

California is home to Buddy.

“Although the last time Buddy’s name came up was a couple of years ago,” says Akins.

Regarding the latest court decision, Akins says, “Another kick at the can gives us all renewed hope.”

For now, wolverines are listed as a candidate species—which receive no statutory protection under the ESA according to a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service explanation of this interim status.

“The FWS encourages cooperative conservation efforts for these species because they are, by definition, species that may warrant future protection under the ESA,” says the agency.

Columbia Insight contributing editor Jordan Rane is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in CNN.com, Outside, Men’s Journal and the Los Angeles Times.