Despite accusations, the Lower Snake River dams plan isn’t a done deal. Only Congress can authorize breaching the dams

Into the breach: Tribes and conservation groups are cheering a plan to make four dams on the Snake River obsolete, including Ice Harbor Dam (pictured). Photo: Wikimedia Commons

By Kendra Chamberlain. December 20, 2023. On November 29, a “leaked” document outlined a Biden administration agreement with states, Tribes and conservation groups to breach four controversial dams located in Washington along the Snake River.

The news sent opponents of breaching the dams into a tizzy of ginned-up outrage.

“The Biden administration has been secretly conspiring with tribal nations and environmental groups,” wrote the conservative think tank American Experiment.

If anything about the Biden administration’s position on the dams was unknown, it’s been the worst kept secret in Washington. The president has been facing pressure to declare his support of the move for more than two years and very clearly tipped his hand back in September.

Last week, the White House released the highly anticipated settlement agreement that aims to boost salmon recovery in the Lower Snake River while developing more renewable energy in the Columbia River Basin.

The agreement doesn’t call for breaching the four dams on the Lower Snake River—only Congress can authorize the breaching of those dams, which are operated by the federal Bonneville Power Administration (BPA).

But it does allocate federal funding and Department of Energy support for the development of tribally owned renewable energy sources.

The settlement is the culmination of 22 years of conflict across four different lawsuits between tribal nations and environmental groups and five federal agencies over the dams and their impacts on salmon.

The resulting Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), between the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon and the Nez Perce Tribe, along with the states of Oregon and Washington and several nonprofits, calls for up to $1 billion in investments along the Lower Snake River over the next decade for salmon recovery and renewable energy build-outs.

Replacing power

Energy generation has been at the center of the litigation and settlement negotiations, which were held in private, a fact that concerned some BPA customers who say they’ve been left out of the negotiations.

The hand-wringing reached a fever pitch when that now infamous draft version of the agreement became public last month and Ore. Rep. Cliff Bentz (R) held a House Committee on Natural Resources oversight hearing on the issue.

Miles Johnson, legal director at Columbia RiverKeeper, which was party to the litigation, said concerns over replacing the hydroelectric energy are overblown.

“Replacing the services of the Snake River dams, from an electrical perspective, it’s just not that big of a lift,” Johnson said. “The Snake River dams don’t produce that much power. Most of the power that they produce is in the spring and summer when the region has way more power than it actually needs.”

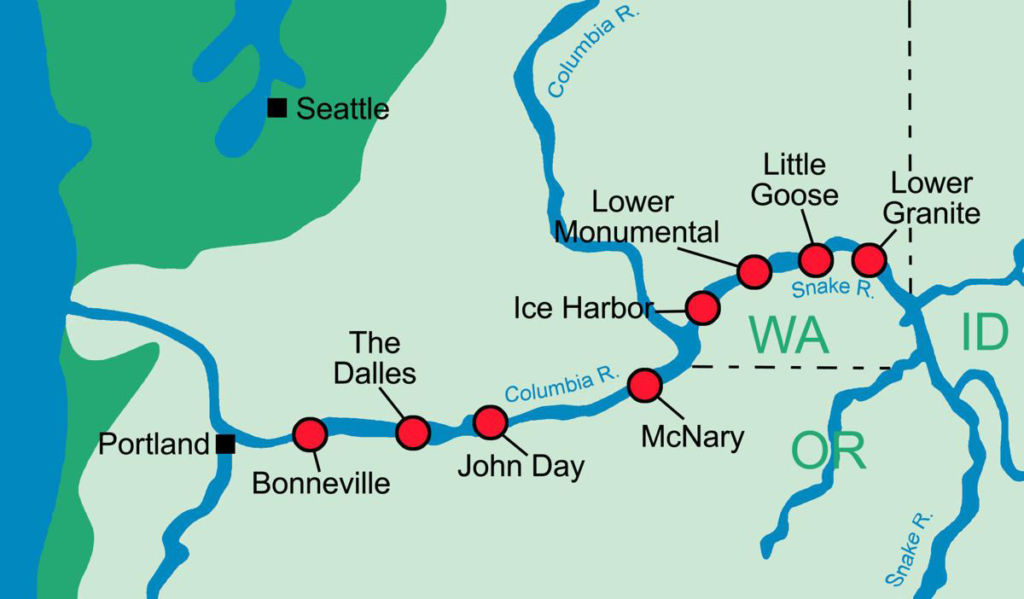

Electric issue: Starting with Ice Harbor Dam and moving east (red dots indicate dams), four Snake River dams have been a bone of contention for decades. Map: USACE

The U.S. Department of Energy will facilitate the build-out of one to three gigawatts of tribally sponsored renewable energy production under the MOU, which may help replace the hydropower with more clean energy resources. But the agreement doesn’t commit BPA to buying that power.

The settlement includes federal promises to fund studies on how removing the dams will impact irrigation and recreation, which environmental groups say will “pave the way” for Congress to authorize breaching the dams in the future.

“Congresspeople in the Pacific Northwest—from both sides of the aisle—understand that the Snake River dams need to be removed if we want to see abundant salmon and steelhead, [and] if we want to honor Tribal treaty rights,” Johnson said. “But at the same time, there are things that need to be done before we can just yank out those dams. And this agreement is designed to deal with a lot of those things.”