Photo by Jurgen Hess

“One generation plants the trees, another gets the shade.” – ancient Chinese proverb

By Dac Collins. Oct. 31, 2019. And if there’s one thing our planet could use more of right now, it’s shade. This past July was — globally speaking — the hottest month on record since record-keeping began in 1880.

Global problems

The effects of a rapidly changing climate were perhaps the starkest in Alaska, where the amount of Arctic sea ice had melted to a record low of 2.9 million square miles by the beginning of July. On Independence Day, temperatures reached 90 degrees in Anchorage, beating the previous all-time temperature record by five degrees. And by July 9th, the Hess Creek fire burning northwest of Fairbanks had grown to over 145,000 acres, making it the nation’s biggest wildfire.

Kenai, Palmer and King Salmon also experienced record high temperatures over the course of the month. But the most astonishing (and troubling) fact about July, 2019 being Alaska’s hottest month on record only becomes apparent when you look at the state’s second hottest month on record: June, 2019.

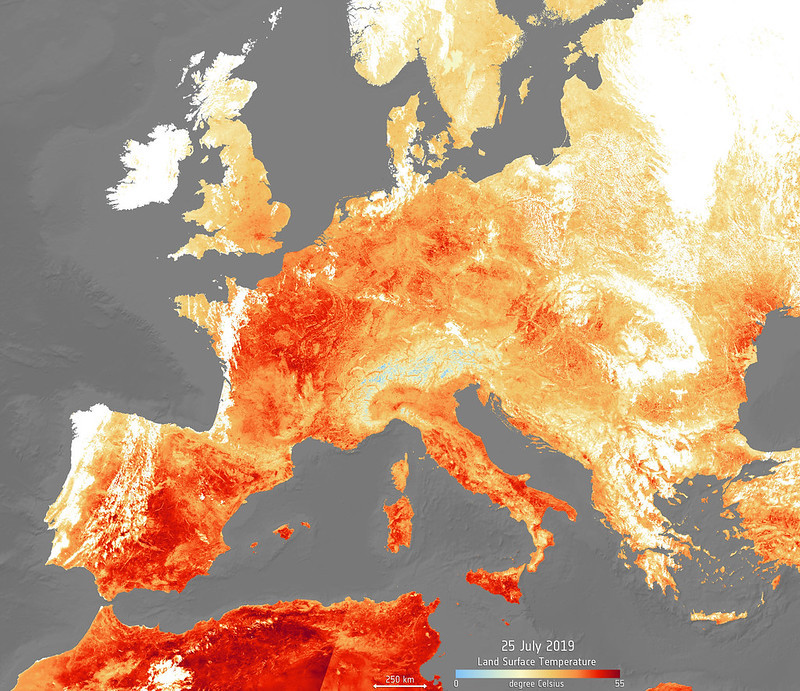

And while thousands of heat-stressed chum salmon were washing up dead on the banks of the Koyukuk, hordes of Parisians swam and splashed in the Trocadero fountains, seeking whatever relief they could find from the back-to-back, record-setting heat waves that hit Europe in June and July.

(It can be difficult to quantify the immediate effects of the climate crisis we’re currently witnessing, but the French Ministry of Health estimated that this summer’s heatwaves caused the deaths of more than 1,400 people across the country.)

Infrared imagery shows the land surface temperature across Europe on July 25. Photo courtesy of the European Space Agency

Signs of the problem are everywhere we look.

The trouble with the solutions, though, is not that they are far-fetched or unattainable — but that they are inconvenient. Ditching fossil fuels, re-designing our electrical grid, changing our eating habits, buying and using less stuff, having less children. These are all worthy, and perhaps necessary, strategies if we are to avoid surpassing the 1.5 degree C threshold of warming that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has cautioned against. They also run counter to our society’s preeminent values of comfort, convenience and consumerism.

And while reducing the overall amount of carbon we release into the atmosphere is paramount, there is another approach to staving off climate change: capturing that carbon before it enters our atmosphere.

We could achieve this by investing in Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) technologies, which are extremely costly and even more controversial. Or we could look to the trees.

And according to a study that was published this summer in Science, planting roughly a trillion more of them around the world might be our most effective strategy.

In the study, researchers with the Crowther Lab in Switzerland pointed to forest restoration “as our most effective climate change solution to date.” They found that the six countries with the most potential for reforestation are (in this order): Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia, Brazil and China. They excluded the land being used for cities and agriculture in these countries and pointed to 0.9 billion hectares (or roughly 2.2 billion acres) of land that would be suitable for reforestation — enough room for an estimated trillion or more new trees.

Birch trees are a key part of Russia’s economy and culture, and they can play a critical role in mitigating the effects of climate change. Photo courtesy of Pixabay

“Once mature,” the study found, “these new forests could store 205 billion tonnes of carbon: about two thirds of the 300 billion tonnes of carbon that has been released into the atmosphere as a result of human activity since the Industrial Revolution.”

Prof. Thomas Crowther, who co-authored the study, emphasized that reforestation is only one part of a larger strategy that hinges on reducing global emissions and protecting our existing forests. And he said that when it comes to planting more trees, we can’t act fast enough.

“Our study shows that tree restoration can be a powerful tool for drawing carbon from the atmosphere. But we must act quickly, as new forests will take decades to mature and achieve their full potential as a source of natural carbon storage.”

Local solutions

Fortunately, some residents of the Columbia River Gorge have already gotten started.

A career wildlife biologist, Bill Weiler lives in Lyle, Wash. and works as the education coordinator for the Sandy River Watershed Council. Collaborating with the Forest Service and the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership, he has helped plant around 1.5 million trees throughout the Sandy River Delta over the last decade.

And just last year, Weiler says, “I’m seeing all this stuff internationally with the UN, and everyone saying, ‘You know, one of the ways we might be able to help with climate change is to plant a billion trees.’ And I thought, ‘Okay. So let’s plant a million here and see if that helps.’”

He says that was around the same time his daughter Chelan and son-in-law Noah Harkin first approached him about starting Trees of the Gorge. They got the (root) ball rolling earlier this year, and the project’s sponsors include Peace Village, Columbia Gorge Ecology Institute, the US Forest Service and the Columbia Gorge Climate Action Network.

The focus of the project is planting native trees and shrubs on public and private land in the middle and eastern parts of the Gorge. Weiler says they chose native plants in particular because they are more adaptable, better for wildlife, and relatively inexpensive.

“White oaks are definitely the best for wildlife,” he says, “because of the acorns. And because when there’s windstorms, frost and ice storms — which are frequent in the Gorge — the branches fall off and rot sets in. And it creates these cavities that are perfect habitat for a number of species.”

“We have a huge oak where we live that has bees, squirrels, and a raccoon all in the same tree. I don’t know how they coexist…but they do,” he laughs.

With an average lifespan of 300 years, native white oaks (Quercus garryana) provide excellent wildlife habitat. Photo by Jurgen Hess

The first Trees of the Gorge planting was on private land in Dallesport, Wash., where a couple who had recently purchased a home was looking to restore a buffer zone around a nearby wetland. And two weeks ago, the group linked up with elementary students from the Trout Lake School to plant pines, maples, spirea and oceanspray on public land in that part of the valley.

So far, they’ve planted around 500 trees and shrubs, and Weiler says they should have closer to 1,500 in the ground by the end of the season.

“There’s a really narrow window for planting here,” he says, explaining that October and November are really the best months to plant trees in the Gorge.

“You want to have a time where it’s either rained or about to rain, but not about to frost. And in Trout Lake, that could happen all in one day. Luckily we’re having this spate of good weather, and the day after we planted up there it rained an inch, which was perfect.”

Weiler says the next plantings are scheduled for Nov. 5 and Nov. 9. The planting on the 5th will take place at the Gorge Discovery Center, and they will be working with high school students from The Dalles to seed balsamroot and plant around 250 white oaks there.

The event on the 9th is open to the public, and it will involve planting a remembrance grove at the Great River Cemetery in honor of women who have had miscarriages. (Located on an 80 acre site near Mosier, Great River will open in 2020 as the first “green cemetery” in the state of Oregon.)

Another important location for the project is Balfour Park in Lyle.

“That’s gonna be the spot where we can plant most of our trees,” Weiler explains. “It’s really fragmented, really weedy, so we can only do good we think.”

“The real question is: when we do plant a million trees, how long will it take before they actually have a positive effect on the climate?”

It’s a good question, and one the next generation might be able to answer.

A crew of school age children plant trees in the Sandy River Delta. Photo courtesy of Trees of the Gorge

Learn More

-

To learn more about Trees of the Gorge, or to volunteer for one of the upcoming plantings, visit the group’s Facebook page.

-

Check out some of the other reforestation projects currently taking place around the world.

-

Request or purchase digital access to the Crowther Lab’s full report, entitled “The global tree restoration potential”.

Excellent article! Timely and there is no more important subject to cover than our climate emergency!

I always feel guilty digging up the myriad acorns the squirrels plant in my yard! Not to mention the maples that get away from me and are 2 – 3 years old.

Is there a possibility that I can transplant them someplace?

Found a species new to me behind the HRFD, a sycamore maple!

I still would love to see a community recognition of the largest of the various species of trees

that we have. Just about the time I think I’ve spotted the largest oak or maple or walnut, I see

another even larger one in someone’s yard!

Wonderful article: so well written and pithy.

I believe the city of Hood River Tree Committee is working to raise awareness of the importance of maintaining urban trees as our city develops so rapidly. Too many trees are being sacrificed to build close-packed town houses that provide no open ground around them for new trees to grow. If this is not your preference, pay attention to the city’s meeting agendas in the coming months. The problem is only worsening.