The Nez Perce Tribe is on a path to reintroduce what Lewis and Clark called “Vultures of the Columbia”

Widespread: Condors were once common throughout North America. Photo: Ken Bohn/San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

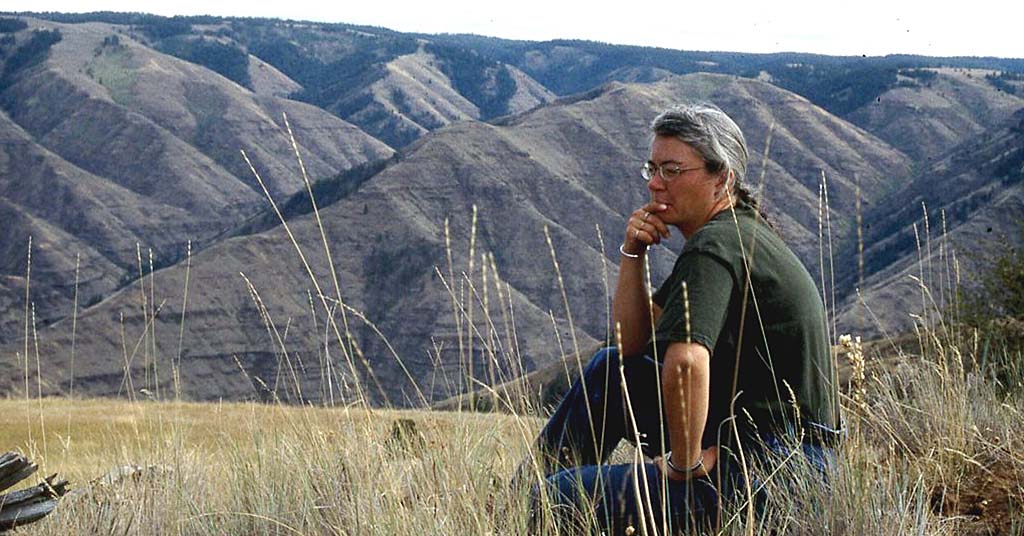

By K.C. Mehaffey. February 8, 2024. Angela Sondenaa was jet-boating up the Snake River through Hells Canyon. Looking at the steep cliffs and rocky crags, an idea struck her: “Man, there needs to be condors here,” she recalls thinking.

It was 2015 and Sondenaa—the Nez Perce Tribe’s Precious Lands Wildlife Area project leader—was surveying for bighorn sheep.

She’d never considered the idea of bringing condors back to the Columbia River Basin, but once it hit her, she says, “This idea would not leave me.”

Sondenaa pitched her idea to the tribe’s wildlife director, and they submitted a grant proposal to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to conduct a condor viability assessment in the Snake River Basin.

Winning the grant in 2016 put the Nez Perce Tribe—or Nimíipuu—on a path that could lead to the first reintroduction of condors north of California since they disappeared from this region about 160 years ago.

If all continues to go well, the tribe will release their first group of captive-raised birds in a yet-to-be-determined location within five to seven years.

History in Columbia River Basin

While there’s no living memory of condors among the Nimíipuu people, this largest land bird of North American—which are called qú?nes in the Nimíipuu language—appears in tribal origin stories, languages and cultural histories throughout the region.

The Nimíipuu’s Ananasocum—also known as Joseph Canyon—roughly translates as “the canyon where condors nested,” says Sondenaa.

There are also early trapper reports of condors, and a record of a military officer who reportedly saw one near the Boise area.

Lewis and Clark were the first Europeans to document their presence in the Columbia River Basin. According to an excerpt from their expedition journals, Clark wrote on Feb. 16, 1806, that two members of the expedition “brought in to us today a Buzzard or Vulture of the Columbia which they wounded and taken alive. I believe this to be the largest Bird of North America.”

Clark went on to describe the condor, weighing 25 pounds with a 9-foot, 2-inch wingspan.

“Skin of the beak and head to the joining of the neck is of a pale yellow, the other part uncovered with feathers is of a light flesh Colour,” he wrote. He included a sketch in his journal entry.

In her element: Nez Perce Precious Lands Wildlife Area project leader Angela Sondenaa. Photo: Nez Perce Tribe

Condors were once fairly common in the Columbia River Basin.

Scientists believe “predator wars” were the main cause of their demise here.

“Folks would take a carcass and lace it with strychnine, attempting to kill cougars, bears and wolves” says Sondenaa.

Since condors only eat meat that’s already been killed, the campaign to rid the countryside of predators had an even greater impact on scavengers, like the condor.

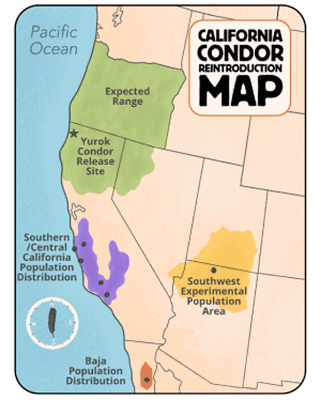

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s most recent five-year review of California condors, the birds were once widely distributed across North America. By the time European explorers arrived, however, they mostly occurred only in the West, from Mexico to British Columbia, and inland to the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Range.

By 1950, they remained in only six counties of California.

“Though no definitive causes of the condors’ decline during the early 1900s have been established, it was likely the result of high mortality rates due to direct persecution, collection of specimens, and secondary poisoning from varmint control efforts” along with DDT poisoning, the status review says.

Numbered species: Condor #480 is a male hatched at the Los Angeles Zoo. He was released as a one-year-old at Bitter Creek National Wildlife Refuge near Ventura. Photo: Timothy Ludwick/USFWS

The agency reports that by 1982, there were only 23 condors left worldwide, and in 1987, the remaining condors were captured for a breeding program in hopes of saving the birds from extinction.

Since then, the population has been rebuilt to more than 500 individuals, more than half of them living in the wild.

Currently, there are six active release sites—four in California, one in Arizona, one in Baja, Mexico.

The most recent reintroduction effort was spearheaded by northern California’s Yurok Tribe, in partnership with the National Park Service.

In 2022—after assessing habitat and working on a plan for 14 years—the tribe released eight birds on ancestral lands in a partnership with Redwood National and State Parks. Three more condors were released there last fall.

Sondenaa says the Nez Perce Tribe has been following the Yurok’s model.

“They’ve done wonderful things, and it’s very exciting to see the successes,” she says.

Favorable habitat

The Hells Canyon Condor Project has been underway for eight years.

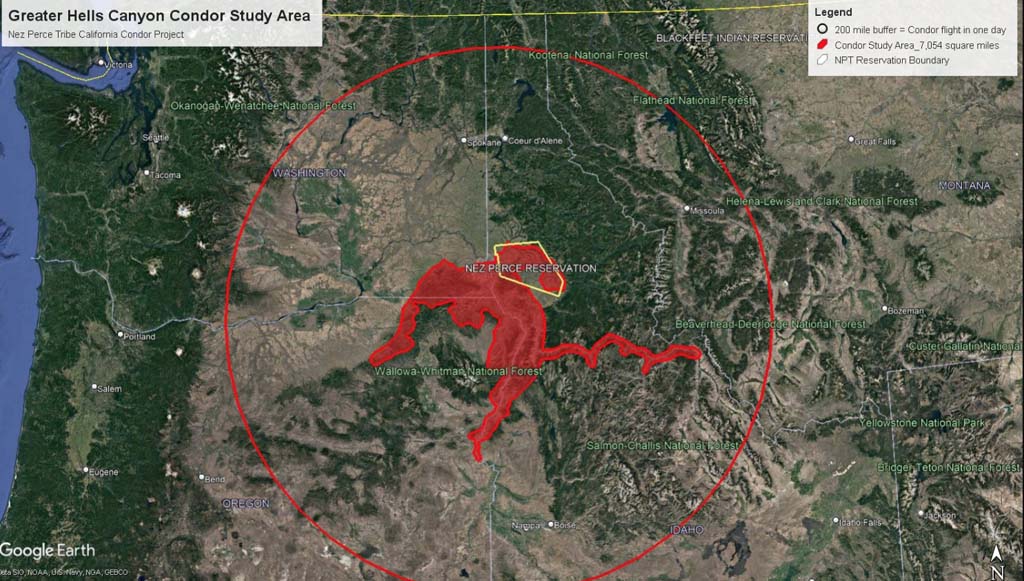

It began with the three-year viability assessment, which included surveying hundreds of miles of shoreline habitat in the Snake River Basin, including parts of northeast Oregon, southeast Washington and western Idaho.

The survey identified condor nesting and roosting sites, foraging habitat and availability of carrion.

Map: Nez Perce Tribe/Hells Canyon Condor Project

Condors are cavity nesters, so they need caves or crevasses in the rock cliffs, along with tall, broken-off trees for roosting. They also feed only on dead animals—usually medium to large mammals.

The tribe surveyed the canyons of the Snake River and its tributaries—the Salmon, Imnaha, lower Clearwater and Grand Ronde rivers, including Joseph Canyon.

They found suitable habitat “in abundance,” says Sondenaa.

Since condors won’t kill for food, they need to have enough carcasses left by hunters or other predators in order to have a self-sustaining population.

Sondenaa says that compared to the habitat and food availability in Arizona, where condors have already been reintroduced, the Nez Perce assessment found just as many—and in some cases, more—of the predators and prey that are needed.

Due to the presence of wolves in the region, condors on Nez Perce ancestral lands would have access to year-round healthy carrion.

“That’s a big advantage that we have here that some other existing populations don’t have,” she says. “Overall, the assessment concluded that condor habitat was really good in our area.”

Map: Oregon Wild

Over 50% of the land is in public ownership, so it’s not likely to be developed. Wind farm development is a potential concern, but that would mostly occur on the periphery of the condors’ range.

As in other areas where condors are now living in the wild, the biggest threat would come from potential poisoning from spent lead ammunition.

“We have a lot of hunters in the area, including tribal members. It’s a cultural endeavor that’s widely practiced among the membership,” she says.

The tribe secured additional funding to conduct an outreach program and is working with tribal hunters and others to convince them to switch to non-leaded bullets, such as copper. The tribe gave away free boxes of ammunition.

“We’ve had really good response from our tribal hunters,” she says.

Cultural legacy

Recently, the tribe won a three-year America the Beautiful planning grant for its project titled, Camas to Condors: Biocultural Restoration Planning for Ananascum.

While restoring condors to the Joseph Canyon area is at the center of the effort, the grant also focuses on other ways to create and maintain a critical wildlife corridor from the Blue Mountains to the Bitterroot Mountains.

The project involves getting the location designated as a new National Heritage Area, and an economic analysis of the impacts of reintroducing condors—which could boost tourism.

“We’ve come a long way, and we’ve gotten very good feedback,” says Sondenaa. “But it’s going to take a coalition to get this to work. We need the support and partnership with states, federal agencies and tribes, along with local landowners and the hunting community.”

Some people have asked why the Tribe is engaged in such a gargantuan effort. Why it’s interested in an obscure bird that’s been gone for such a long time.

“For the Nez Perce Tribe, it’s important spiritually as well as ecologically,” says Sondenaa. “It shows a commitment to the homeland, and to the ecology of this special place.”

Columbia Insight’s reporting on biodiversity in Oregon is supported by the Autzen Foundation.

Columbia Insight’s reporting on biodiversity in Oregon is supported by the Autzen Foundation.