Biophilia explains our love of nature. Paying attention to it is an overlooked part of conservation

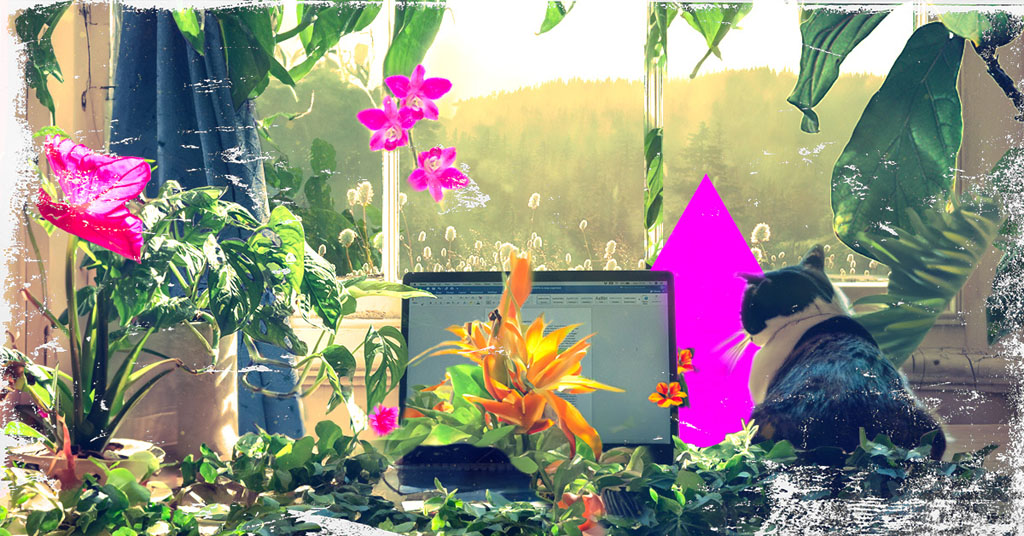

Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

By Aaron Gilbreath. August 24. 2023. Climate news this month has been cataclysmic.

Wildfire haze hanging over the Pacific Northwest. Mounting casualties from the tragic fire in Maui. More fires causing the evacuation of all 20,000 residents of Yellowknife in Canada. Record high temperatures set from Florida to Portland to Japan to Iraq as the planet heads toward its hottest year on record. Trees moving into the warming north in what’s called “arctic greening.”

So when our family took a vacation to Sunriver in central Oregon, I designated a week to ignore environmental apocalypse.

I’d spent the last month telling friends how America’s plastic recycling system is flawed and why I was quitting beef. This week I just wanted to dance to the Grateful Dead in the rental cabin kitchen without discussing current events.

Was I conflicted or escaping? Irresponsible or exhausted?

Instead of focusing so much on our warming planet’s destruction, the trip presented an opportunity to reconnect with the natural world that had made me an environmentalist in the first place, and to continue showing nature’s wonders to our daughter: wildlife, aimless bike rides, radiant sunsets.

Something deeper than neurobiology was at play here.

My soul’s tank felt empty. How do you recharge something you can’t even see?

Science couldn’t measure, let alone name, the soul, but something like it was there, some key element of our humanity that encompassed the parts of our body that profoundly affected our health, mood, our sense of cosmic connection and purpose.

I’d started buying books that explained this.

At the root is something called biophilia.

Translating to “a love of life,” social psychologist Erich Fromm first defined the hypothesis in 1973.

Harvard sociobiologist E.O. Wilson refined the concept and took it to the masses, defining biophilia as “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms.”

Not only does that affiliation help our species survive, argued Wilson, it helps us find tranquility and satisfaction in our surroundings.

The idea is that we’re inherently drawn to the natural world because we, as animals, evolved in the natural world, and our health is directly impacted by how much time we spend in nature versus what we spend in modern, built environments.

According to Wilson, human beings’ nervous systems evolved in nature, so we’re more used to—and more comfortable in—natural, non-human environments than we are in the urban environments we increasingly occupy.

“In short,” Wilson said, “the brain evolved in a biocentric world.”

In a real sense, nature is our nature.

Dueling tendencies

In 2008, more people lived in cities than outside of them for the first time in history, officially making homo sapiens an urban species.

Despite this—maybe because of it—biophilia is everywhere.

You see it in kids at petting zoos.

You see it when you fill your house with potted plants and water your garden.

When you hang a hummingbird feeder, feed ducks at the park, choose to drive down a wooded street instead of a treeless street, biophilia drives your behavior.

Biophilia is why kids love stuffed animals and why adults put up with torn couches and soiled rugs to keep pets.

Balancing the need to stay informed with the need to stay sane is an inaccurate science.

Our physiology is still that of a non-urban species.

Economics, class, fate, habit, choice—so many factors prevent access to nature and keep us indoors.

The trend is accelerating.

“By 2050, 66% of the world’s population is projected to live in cities,” Time reported.

The average American spends 93% of their time indoors.

And indoors, we’re glued to devices.

“American and British children today spend half as much time outdoors as their parents did,” writes Florence Williams in The Nature Fix: Why Nature Makes Us Happier, Healthier, and More Creative.

Proving biophilia

When I first encountered the term biophilia in my twenties, it explained a lot: why I’d always loved animals, why I always had pets, why I was increasingly drawn to the natural world as a college kid and why so many of us feel so comfortable camping and so alive in wilderness.

It’s why I prefer to work on my laptop beside the bamboo in our backyard rather than the basement.

Williams’ book explains the physiological dynamics behind our connection.

Yoshifumi Miyazaki, the vice director of the Center for Environment, Health and Field Sciences at Japan’s Chiba University told Williams, “Throughout our evolution, we’ve spent 99.9% of our time in nature. Our physiology is still adapted to it. During everyday life, a feeling of comfort can be achieved if our rhythms are synchronized with those of the environment.”

Guided by the biophilia hypothesis, Miyazaki’s research proves that human physiology benefits from particular kinds of habits.

“He and his colleague Juyoung Lee,” writes Williams, “found that leisurely forest walks, compared to urban walks, deliver a 12% decrease in cortisol levels. But that wasn’t all; they recorded a 7% decrease in sympathetic nerve activity, a 1.4% decrease in blood pressure and a 6% decrease in heart rate.”

Through formal research, Japanese scientists are actively studying how and why the great outdoors rejuvenates us, reduces stress, improves creativity, enhances our immune systems and improves our moods.

In his essay “Walking,” Henry David Thoreau wrote, “I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least—and it is commonly more than that—sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.”

“The Japanese work is essential in my mind,” Harvard Lecturer Alan Longan told Williams. “We have to validate the ideas scientifically through stress physiology or we’re still at Walden Pond.”

Peaceful warrior

Sunriver time passes slowly.

Deer nibble outside your front window in the morning. After breakfast, you go rafting, horseback or bike riding after lunch.

Eating dinner on the back patio, the setting sun streaks the hazy sky in neon pink, and you catch tiny frogs on the riverbank after dark.

We took our daughter to the High Desert Museum in Bend for a raptor show, where a rehabilitated peregrine falcon, Swainson’s Hawk and a barn owl swooped over the audiences’ head, occasionally smacking their wings into our arms while traveling tree to tree.

We took her floating six miles down the swollen Deschutes River, where ducks followed our boat and osprey circled overhead.

Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

Here, I found myself at peace with nature, not obligated to be a nonstop eco-warrior.

I relearned to shift my focus from climate news, and I planned to spend more time outdoors after this vacation ended.

But could I integrate those two parts of my life better back in the city?

No matter how unhealthy the practice, I’d become psychologically dependent on keeping up-to-date with environmental news.

Balancing the need to stay informed with the need to stay sane is an inaccurate science.

I’m sure there’s science about the effect information overload has on a person, but I haven’t searched for it because I already have too much to read in my pile.

It’s not just depressing environmental news.

I don’t like staring at phones. I especially hate scrolling through them. Scrolling feels poisonous.

To protect my health and model behavior for my daughter, I created rules: never look at phones while eating at the table, never before bed and never on walks.

Despite combating it, modern life has still left me feeling so nervous, just nervous.

I didn’t used to be this way, but my stomach is filled with too much bile, my chest electrified with more cortisol than it should have, leaving me uneasy day and night.

But away from endless news of environmental disaster, my stomach unclenched, my jaws quit grinding at night and I slept more deeply.

Remembering why we fight

Of course, in the connected age, the world wouldn’t entirely let me forget.

Going from a news buffet to a news famine left me feeling dangerously malnourished, so I snuck some news one night.

A “hurriquake” in Southern California? What the hell was that?

I put the phone down. But that didn’t stop the worries.

For how clean as it is, reminders littered Sunriver: beer cans in the river, trash on the side of the road, never mind all the waste generated from us visitors. The pool cafe poured smoothies into plastic cups with plastic straws and used compostable bowls whose surface treatments probably made them non-compostable.

Like treating environmental news as something to turn on and off, by ignoring the news you ignore its connection to you.

I pondered a healthier perspective.

Being an environmentalist isn’t solely about being active and enraged and debating solutions to our civilization’s challenges.

It also involves loving the thing you’re devoted to saving: nature, open space, living things, empathy, cooperation, inner peace.

Contrary to my initial fears, by devoting the bulk of our vacation to biophilia I wasn’t ignoring reality or indulging ignorance on vacation.

I was retraining myself to include more nature in my environmentally minded life.

Hike, camp, float a river.

As an environmentalist, time in nature reminds me why I care so deeply in the first place.

I did not like the form and structure of so many sentences. Confused me reading this report.

Yep. (Meaning, I can relate to this story and appreciate it).

Thank you for this reminder! Of course, all of us who care deeply about our living planet are biophilists (sp?) and feel the stress mother nature is under every day. Reading your story, I found myself saying, to myself, “I can’t unplug that way….. I would feel too guilty” as if reading, and bearing witness to the unraveling of our world is a job that cannot be shirked. But I know you are right. We are useless in this battle if we don’t take time to appreciate why we are in it to begin with….. so in several weeks I will head up north, Vancouver Island, to camp and hang out with my spouse, my dogs, and whatever wildlife we can photograph from a distance, while reveling in the emerging signs of autumn that we hope brings some respite from heat and wildfires for our suffering planet.

Aaron, well written. The message is clear. We need to get into nature, let in fill our soul, recharge our batteries. Then get back into the fight. We did that at Mt Adam’s Bird Creek Meadows last Sunday. Nature replenished us and now back into the battles.