Tribes Speak up for Ecosystem Needs During Columbia River Treaty Negotiations

This is part two of a series of articles about the Columbia River Treaty. For more background on the Treaty, read A New Columbia River Treaty: A balancing act spanning two countries and a diversity of interests

By Dac Collins. May 9, 2019. The federal government of Canada announced on April 26 that it is inviting three First Nations to participate as observers in the ongoing Columbia River Treaty negotiations between Canada and the United States. And while 15 tribes in the U.S. are still feeling excluded from the negotiating table, they see this development as a step in the right direction.

That’s because tribes on both sides of the border share a common goal: to integrate ecosystem-based function into the modernized treaty. This would require a more holistic approach to managing the four Treaty dams, which means taking into account fish, wildlife, habitat, water quality and the overall health of the river while still meeting the needs of hydropower and flood control.

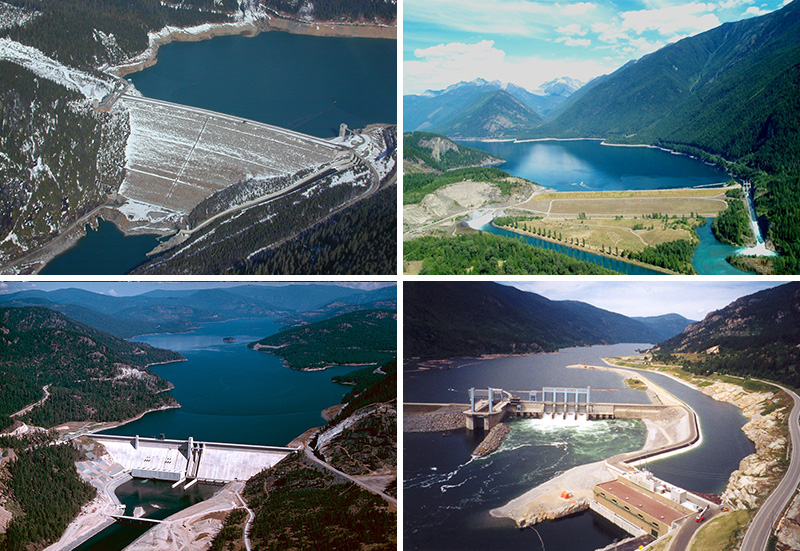

Arranged sequentially (clockwise from top-left), the four Treaty dams — the Mica, Duncan and Keenleyside Dams on the Canadian side and the Libby Dam on the U.S. side — are located in the upper reaches of the Columbia River Basin. Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The inclusion of the Ktunaxa, Okanagan and Secwepemc Nations comes nearly a year after the Treaty negotiations began last May. Indigenous leaders and representatives say they look forward to working with U.S. and Canadian Entities to modernize the transboundary agreement before it expires in 2024…but they say the invitation is long overdue.

“The original Columbia River Treaty in 1964 excluded our Nations, and wreaked decades of havoc on our communities and the Basin,” said Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Okanagan Nation Alliance.

“Canada’s unprecedented decision to include us directly in the U.S.-Canada CRT negotiations is courageous but overdue, and necessary to overcome the decades of denial and disregard. We welcome the government’s bold decision here and look forward to helping to ensure any new Treaty addresses the mistakes of the past.”

Phillip’s welcoming of the government’s decision is a step toward reconciliation, as he and other First Nations leaders were outraged when they learned that Indigenous peoples were not invited to participate when the negotiations first began. He called the exclusion of those voices a “total slap in the face”, while Chief Wayne Christian, representing the Secwepemc Nation, referred to the snub as “business as usual”.

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Okanagan (Syilx) Nation is the current President of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. Photo by Josh Berson, Protect the Inlet

But Phillip and Christian aren’t the only ones who have felt slighted during the negotiation process. There are 15 tribes scattered throughout the Columbia Basin on the U.S. side of the border — none of which have been offered a seat at the negotiating table.

The State Department, which is heading up the U.S. negotiating team, says it “values the Tribes’ expertise and experience, and is consulting with the Tribes throughout the negotiating process.”

And responding to the news from our northerly neighbors, a State Dept. spokesperson for Western Hemisphere Affairs says: “We will continue to engage the Tribes on a regular basis as negotiations proceed,” but “we have no plans to change the general composition of the team.”

As the Director of Government Affairs and Planning for the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Louie Pitt says this is disheartening.

“We Warm Springers gave 10 million acres to the United States. We gave real land, real water, real resources…a lot of real things,” Pitt says. “Shouldn’t that count for something?”

Like Christian, Pitt sees the disconnect between federal and tribal governments as a systemic problem — one that dates back to long before the Columbia River Treaty was ratified in 1964. At the root of this problem, Pitt says, is the fact that when it comes to managing the Columbia, U.S. interests have never aligned with those of the tribes.

“I was broken-hearted when I grew up and found out that Grand Coulee Dam just said ‘hell no’ to fish passage,” Pitt says. “All that beautiful habitat up there, and these great scientists and engineers couldn’t think of a way to get fish past that? Give me a break. It just wasn’t important to them.”

Fortunately for Pitt and the other tribal leaders in the Basin, they have staff working for them on this issue. Intergovernmental organizations such as the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC), the Upper Columbia United Tribes (UCUT) and the Upper Snake River Tribes Foundation (USRT) are helping ensure that the tribes’ concerns are heard and acknowledged.

Jim Heffernan works for CRITFC as a policy analyst for the Columbia River Treaty. Providing policy support for the Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla and Nez Perce, he explains that the four tribes initiated a process to create a larger Tribal Coalition, which serves to consolidate the concerns of the 15 sovereign nations into one united and cogent voice.

This map shows the 15 tribes on the U.S. side of the border that are affected by the Columbia River Treaty. Click here for a more detailed map of the Columbia River Basin that shows the location of tribal lands on both sides of the border. Maps created and provided by CRITFC

“The thing that the tribes are pushing for hardest is integrating ecosystem-based function in a modernized treaty,” Heffernan says, emphasizing that there are a number of ways that Canada and the U.S. could accomplish this goal. One example would be “changing the operations of the reservoirs so we can get more water into the system in low to moderate water years.”

More specifically, he explains, this would mean restoring at least 3-5 million acre feet of flow in the spring and early summer in those low to moderate water years, when juvenile salmon (headed downriver) are most vulnerable to the impacts of dams.

Adjusting the flow regime of the Treaty dams to restore this “spring freshet” would be a major change to the current Treaty provisions, which were implemented in ’64 to serve two explicit purposes: to coordinate flood risk management to protect downriver communities, and to operate the reservoirs in a way that optimizes hydropower production. And for some utility companies, dam operators and ratepayers along the Columbia River, sacrificing this much water (and potential electricity) to benefit migrating fish is a hard sell. Mainly because they’ve grown accustomed to the idea that the water is theirs to manage.

But from the perspective of the tribes, who honored and relied on the Columbia’s natural resources for thousands of years before the United States and Canada came into existence, this way of thinking is not only insulting and narrow-minded…it speaks to the greatest injustice in their history of the River.

So when stakeholders tell them that integrating ecosystem-based function is going to “cost them too much” in lost hydropower potential, Heffernan says, all tribal leaders can do is “look at them stone-faced and tell them: ‘You’re using our shared resource, and in a manner that is impacting our other resources. You didn’t consult with us when you implemented the original Treaty, and the way you’re managing it now detrimentally impacts our resources to the point that there are now several listed stocks.’

‘You’ve over-utilized the water and you’re assuming that you own it. But you don’t own the river.’”

Members of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation are reminded of this inequity by the presence of Grand Coulee Dam. One of the largest concrete structures in the world, it inundated Kettle Falls. And along with Chief Joseph Dam, which also lacks fish ladders, it represents the end of the road for migratory fish in the Columbia.

Completed in 1942, Grand Coulee Dam became a permanent barrier to salmon, steelhead and other migratory species such as sturgeon and lamprey. It cut off some of the best spawning habitat in the Basin, effectively stripping the upriver tribes of their primary food source and their identity.

Forming Lake Roosevelt in Central Washington, the Grand Coulee Dam produces more hydroelectric power than any other dam in the Columbia River Basin. Built in 1942 without fish ladders, it is also the most significant barrier to migrating fish in the Basin.

“We were all salmon people,” says Rodney Cawston, Chairman of the Colville Tribal Business Council. “Our culture, our religion, our way of life. Everything revolved around having salmon come up the river.”

So when Cawston talks about the changes he would like to see in a modernized version of the Columbia River Treaty, restoring fish passage over Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee Dams tops the list.

“If there’s one thing that could have a huge impact on the tribes — the Colville Confederated Tribes and all the tribes that are north of us on the Columbia — it would be to see fish passage,” Cawston says.

And according to Heffernan, this is something that both countries should at least be thinking about. He explains that “both the U.S. and Canada agreed to block passage above Grand Coulee. And through the Treaty, they collaborated in turning the river into an organic machine that mainly runs for the sake of power production and the consequential benefits of coordinated flood risk management.”

All the tribes are asking for in the current treaty negotiations, Heffernan says, is for the two governments to “redial the system so that ecosystem function is built in.”

“And fish passage above Chief Joe and Grand Coulee is something the parties should be studying,” he says.

Heffernan points to the U.S. Entity’s Regional Recommendation for the Future of the Columbia River Treaty after 2024. The product of a multi-year collaborative effort between federal agencies, state governments, tribes and additional stakeholders, it recommends that: “The United States should pursue a joint program with Canada, with shared costs, to investigate and, if warranted, implement restored fish passage and reintroduction of anadromous fish on the main stem Columbia River to Canadian spawning grounds.”

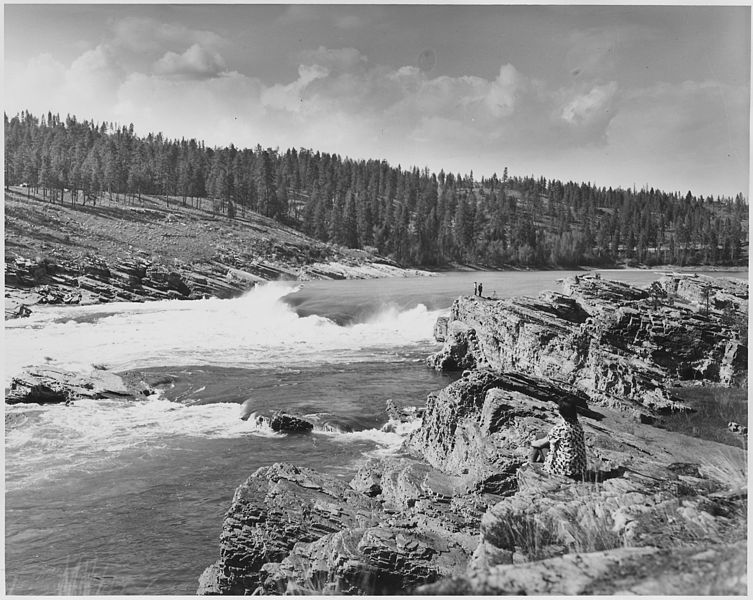

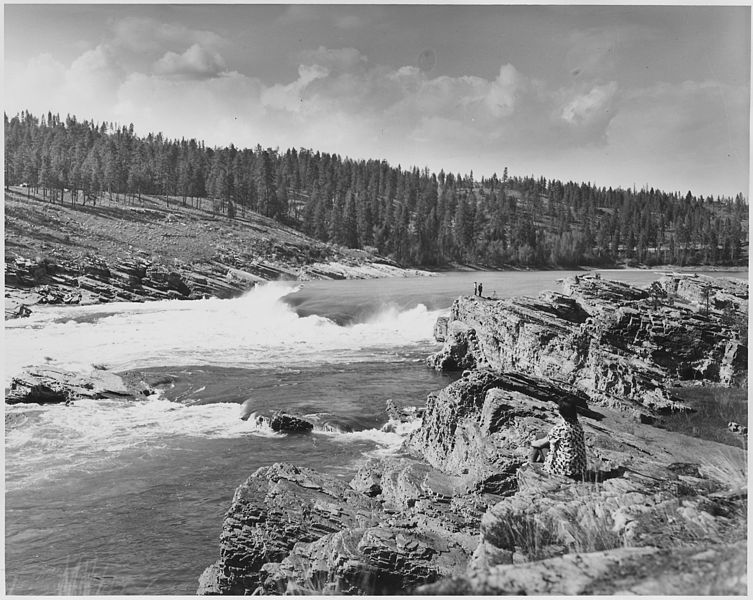

Now buried beneath Roosevelt Lake, Kettle Falls (pictured here in 1939) was once one of the most important fishing and gathering places for Native Americans in the Northwest. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Restoring a population that has been absent for over 80 years is an ambitious goal, however, and the inclusion of the Ktunaxa, Okanagan and Secwepemc Nations in the current Treaty negotiations does not guarantee that it will happen. But it does mean that the ecosystem of the Columbia River will have a stronger voice at the negotiating table. And for Pitt, Cawston, Phillip, Christian and the other tribal leaders of the Basin, being heard is half the battle.

“Everything that we have as a native people is entwined with that resource. And any consideration that we’ve gotten today, we had to fight for it in court,” Cawston says.

“And we will continue to fight for it if we have to.”

So far, six rounds of negotiations have taken place between the U.S. and Canada. According to the State Dept. website, the next round of negotiations will take place in Washington D.C. on June 19 and 20.

The negotiations will continue for the foreseeable future. Town hall meetings soliciting input are expected to continue, and these meetings are open to the public.

To receive regular updates regarding the Columbia River Treaty and upcoming town hall meetings, email: ColumbiaRiverTreaty@state.gov

Good article, cogently written, informative links, and timely subject matter. It seems that the “past” really is “prologue” for the dismal treatment of the tribes on both sides of the border. Hopefully this will change.

Thank you for the excellent article. As a volunteer researcher, I plan to place this article in the archives of the History Museum of Hood River County.