Burning trees to make electricity is a thing. No wonder international markets are eying forests across the Pacific Northwest

Burn notice: If plans are approved, new wood pellet plants, like this one in North Carolina, will turn Northwest trees into electricity for Europeans. Photograph: Southern Environmental Law Center

By Nick Engelfried. April 4, 2024. Hints of a southern accent come through in Rita Vaughan Frost’s voice when she talks about the woods in Texas where she spent much of her childhood.

“Ever since I was a little girl, I loved playing in forests,” says Vaughan Frost, who works for the Natural Resources Defense Council as a forest advocate based in Oregon. “They were where I went camping with my family and learned to fish with my dad. They have a lot of importance for me and other southerners.”

Southern forests have been extensively logged for over a century. However, beginning about a decade ago, Vaughan Frost watched a new industry with a massive appetite for wood begin meteoric growth in the region.

Companies that turn wood into pellets for use as biomass energy are accused of causing a surge in deforestation in the South, all in the name of producing renewable energy for international markets.

Now, that industry has its sights on the Pacific Northwest.

At least four large wood biomass processing plants are proposed for construction on the West Coast, three of which are likely to source fiber from Northwest forests.

In Washington, British company Drax wants to process up to 450,000 metric tons of wood annually at a Longview facility, while Pacific Northwest Renewable Energy seeks to build a similarly sized project in Hoquiam.

Both would manufacture pellets for export.

In California, Golden State Natural Resources, which ratified a memorandum of understanding with Drax in February, has proposed building two biomass pellet export plants.

Located in Tuolumne and Lassen Counties, their combined capacity adds up to 1 million tons of wood per year.

A map of the company’s projected “working area” shows the Lassen County plant sourcing wood from Oregon timberlands east of Grants Pass.

The industry claims wood to feed these plants would come mainly from forest residues such as sawdust or leftover logging slash.

However, multiple investigations published in the last few years appear to show biomass companies in other parts of North America turning whole trees, including some from old growth forests in British Columbia, into pellets.

“The sheer size of these projects in the Northwest will absolutely require inputs that are more than forest thinning or mill residues,” says Vaughan Frost. “I’m worried the volume of demand for wood needed to keep them operating will push them far outside the realm of activity that has any ecological benefits.”

Green energy narrative

Undergirding the logic of West Coast biomass export plants is a narrative that they will produce green, renewable energy for international markets while contributing to sustainable forestry at home.

“Of course they’re sustainable,” says Cindy Mitchell of the Washington Forest Protection Association, an industry group. “You have trees that are growing every year. And the trees in our state, especially on the west side of the mountains, have the fastest growth rate of any in the country. Why would a company put money into a plant if they don’t have a sustainable source of harvest?”

At the heart of the controversy over forest biomass are fundamental disagreements about what words like “sustainable” mean.

Industry tends to define sustainable forestry as management that allows wood to be harvested indefinitely, year after year.

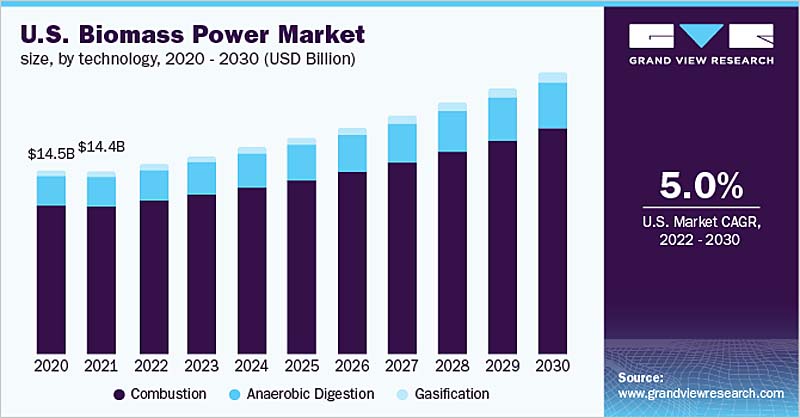

Chart: Grand View Research

Environmental groups see the term as involving a more holistic approach that maximizes biodiversity protection and carbon storage. This may mean leaving in place wood residues the biomass industry regards as waste.

“Logging for timber already removes significant forest biomass in the form of trees,” says Janet Strong, President of the Grays Harbor Audubon Society. “However, they often leave behind some slash, which feeds nutrients back into the soil.

“Now the biomass industry wants to take out whatever logging companies leave behind. Well, that removes even more nutrients and wildlife habitat.”

Grays Harbor Audubon is one of over 60 environmental and community groups that signed a letter urging the Olympic Region Clean Air Agency to reject a key permit for the Hoquiam biomass plant.

Concerns raised in the letter include the biomass industry’s potential impact on forests and the global climate, as well as localized air and noise pollution.

Environmental groups have similar fears about the other West Coast pellet plants.

“Here in Washington, there’s a growing movement to protect older forests so they can become old-growth and repair habitat that’s been lost,” says Strong. “But biomass is an industry with the political muscle to override concerns about long-term forest health. It’s very troubling to me.”

Just how renewable?

Drax, which is involved with three of the four West Coast biomass projects, claims it doesn’t contribute to deforestation or harming older forests.

“[The] Longview [plant] will receive its fiber in the form of sawmill residuals from established and well-respected companies with strong sustainability practices,” a Drax spokesperon told Columbia Insight in an email. “Our review noted that the area’s forest industry businesses have robust sustainability platforms which provide a high level of confidence that the fiber sourced from their woodlands will continue to support nature, people and climate positive outcomes.”

According to Mitchell, state regulations prohibit trees in Washington from being harvested solely for biomass.

“There is a collaborative definition of what biomass is in our state,” says Mitchell. “It’s not old-growth or older growth. It’s leftover residues from timber harvesting, and forest health treatments.”

Rules related to biomass harvest vary depending on whether a forest is on state, federal or private land.

On state trust lands, Washington’s Department of Natural Resources “defines biomass as the byproduct of harvesting activities and we interpret that to mean tops, branches, some stumps, basically logging slash,” Duane Emmons, DNR’s assistant deputy supervisor for state uplands, told Columbia Insight in an email. “We have specific biomass contracts that we use when selling just biomass (selling slash piles), and that doesn’t involve the harvesting of any trees.”

Emmons said another rule applying to state and private lands in Washington defines forest biomass as “material from trees and woody plants that are by-products of forest management, ecosystem restoration or hazardous fuel reduction treatments on forest land.”

Logging away forest fires?

DNR rules are superseded by federal law in national forests, but projects with stated goals to combat wildfires represent a possible source for biomass harvested from these lands, too.

In the wake of recent large wildfires, the forest industry and some policymakers have called for more logging in both state and federally managed forests.

“Renewable fuels should be something we all celebrate as another market for biomass that will otherwise create dead and dying overgrowth until we get into a forest fire situation,” says Mitchell. “It’s going to burn one way or the other. So, do we turn it into a product or let nature take its course of devastation and destruction?”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Biomass is an industry with the political muscle to override concerns about long-term forest health.” —Janet Strong, Grays Harbor Audubon Society[/perfectpullquote]

There’s widespread agreement among scientists that decades of fire suppression in the West made large, destructive wildfires more likely, and that climate change multiplies the risk.

However, the effectiveness of logging as a solution is far less clear.

A 2022 paper in the peer-reviewed journal Biological Conservation stated that “industrial logging and thinning may reduce [forest] resilience” compared to prescribed burns and cultural burning practiced by Indigenous nations, while arguing against “pre- and post-fire logging that may destroy natural forest regeneration and increase fire hazards.”

“Biomass companies want to profit by positioning themselves as agents of forest wildfire resiliency,” says Vaughan Frost. “I think they’re playing on people’s very justified fears of fire in order to profit from thinning projects that have not been shown to have any real benefit.”

“We take giant, whole trees”

A series of high-profile incidents in which biomass companies were accused of violating sustainability policies have cast a shadow over the industry as it seeks to establish itself in the Pacific Northwest.

In late 2022, the nonprofit news platform Mongabay published a whistleblower’s allegations that biomass company Enviva was logging large trees in North Carolina.

“We take giant, whole trees,” the whistleblower, who formerly worked at an Enviva plant, told Mongabay. “We don’t care where they come from. The notion of sustainably managed forests is nonsense. We can’t get wood into the mills fast enough.”

Enviva, which filed for bankruptcy in March, is not directly involved in the proposed West Coast biomass plants. However, its claims about sustainability resemble those of other industry players.

“We source from landowners who intend to return their land to forest and create a market for their low-value wood,” says Enviva’s sustainability webpage. “This augments the productivity of their working forests as we are purchasing the parts of the harvested wood that are generally not utilized in other higher-value markets.”

Drax has also faced accusations of logging sensitive forests.

In 2022, the BBC reported using satellite images, drones and logging licenses to trace logs processed in Canadian Drax mills back to British Columbian old growth forests.

A response from Drax released soon afterward said, “Canada has some of the most highly regulated forests in the world,” and that, “As anyone in the BC forestry industry knows, the forests there are not harvested for biomass, they are harvested for high value timber used in construction.”

However, Drax did not directly refute the BBC findings.

A follow-up BBC story published in February claimed BC Ministry of Forests documents showed Drax continuing to source wood from old growth forests.

The company’s response included the statement that, “We are confident our biomass is sustainable and legally harvested.”

In the U.S. Southeast, where Vaughan Frost watched the biomass industry take root, a study commissioned by the Southern Environmental Law Center found deforestation in Virginia and North Carolina increased significantly after biomass pellet plants began operating in the region.

“From the get-go, these companies have claimed to use sustainable practices,” says Vaughan Frost. “But it’s important to understand what that has actually looked like in places where they’ve operated for years.”

Rocky start in the Northwest

Earlier this year, Longview resident Ian Thompson heard from a friend about a large structure going up on the site of Drax’s proposed pellet plant.

“I went to investigate,” says Thompson. “Sure enough, there was this huge, white dome being built. I thought, that can’t be Drax, they haven’t got their permit yet. But it was. They were building a wood pellet holding tank.”

None of the proposed West Coast biomass export plants has received all the permits needed to begin operating, as of now.

This includes Drax’s Longview plant.

Biomass bubble: The Drax dome in Longview, Wash. Photo: Diane Dick

Burst: Shortly after it went up, the Drax dome was taken down. Photo: Diane Dick

On March 13, the Southwest Clean Air Agency (SWCAA) sent the company a notice of violation for beginning construction prematurely. SWCAA enforces the Clean Air Act and related laws in southwestern Washington.

Drax told Columbia Insight the company had believed its work at the Longview site constituted “permissible construction activity” to engage in while waiting for a permit, and that it has been halted. This hasn’t assuaged the concerns of some residents.

“They’ve already been caught building illegally and got called on it,” says Thompson. “We shouldn’t need any more examples of whether this company is a good player who can be trusted.”

Drax received another setback on March 21, when SWCAA withdrew a draft permit for the Longview plant, citing need for further review.

A public hearing on the permit was cancelled, though it will likely be rescheduled.

Of the four proposed West Coast biomass export plants, Drax’s Longview facility is arguably furthest along in the permitting process, and its rocky start illustrates some of the challenges the industry faces as it seeks to win favor from the public and policymakers.

“We’re not at the stage where any of these companies can begin logging Northwest forests yet,” says Vaughan Frost. “Their PR makes biomass look really good from the outside, and as they seek to establish themselves here it’s important people understand their true history and the scientific facts.

“This is a growing industry, and anything we see get a foothold now will likely spell even bigger expansion later.”

Thanks for this article. Good work, and takes me to a deeper understanding and definitely some new issues, I did not know about,.

More great reporting! We definitely need to learn about this threat to our ‘neighborhood’.