By Dac Collins. March 7, 2019. Over 1,800 cows died last month when a blizzard of unprecedented proportions hit the Yakima Valley. And with a number of local farmers claiming they’ve never experienced such a severe winter storm, some people are wondering if this was simply a freak occurrence or if it somehow correlates to the volatility of a changing climate.

The Lower Valley received the brunt of the storm, which struck on the evening of Feb. 8. Yakima Mayor Kathy Coffey declared a state of emergency the following afternoon, and by the end of the weekend 14 dairy farms had reported losses of cattle.

“In all my years, I’ve never been a part of a blizzard like this,” Jason Sheehan, owner of J and K Diary, told the Spokesman Review.

“If we would have gotten the snow without the wind, we would have been fine,” Sheehan continued. “Even if we got the wind without the snow, we could have figured something out. But when you put the two together, it was like nothing I have ever seen.”

Sheehan and other dairy operators were wholly unprepared for a storm of this magnitude. Because of the dry desert climate in the Yakima Valley, many of the cows there are either left outside during the winter months or kept in open-sided shelters.

And with wind gusts of 80 mph, snow accumulations of up to two feet and temperatures plunging to 20 below zero, some of those cows froze to death before farmers could move them into barns and improvised shelters.

Hundreds more of the animals were trampled by one another as they tried to escape the wind by cramming into the corners of pens.

All told, representatives from Washington’s dairy industry reported that 1,830 cows (an estimated $4 million worth of dairy products) were killed in the storm. And while it doesn’t make up for these losses, the State has already provided $100,000 to help remove some of the dead cows.

Dave Bennett is the Communications Manager for the Washington Department of Ecology’s Solid Waste Management Program, which was tasked with coordinating the proper disposal of the animal carcasses. He says they finished with that operation two weeks ago.

“Most of the carcasses were managed appropriately by the farmers themselves,” Bennett says. He explains that only about 500 of them had to be taken to a landfill in Oregon. The rest were either rendered or composted by farmers, which means the carcasses had some beneficial use associated with them.

Bennett refers to the disposal operation, and to the blizzard itself, as “unprecedented and very unusual.”

“This is not something that we look forward to…or prepare for. It’s something that we respond to,” he says. “This was not easy for anyone.”

There is, however, another more theoretically challenging component of this storm: the notion that these devastating weather events could become more commonplace if the climate continues to warm at its current rate.

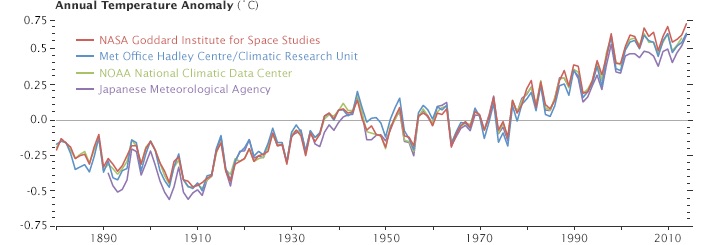

This graph shows the increase in average global temperature between 1880 and 2014. Courtesy of NASA’s Earth Observatory.

Climatologists are still grappling with this idea, and many would consider it a stretch to try and draw direct correlations between one unusually severe winter storm and climate change. But that hasn’t kept some of them from trying. A 2018 study seeks to explain how a warming Arctic could be responsible for some of the brutally cold weather that we are witnessing in the northeastern United States.

Karin Bumbaco, Assistant State Climatologist with the University of Washington, falls somewhere between the two camps when answering the sticky (and increasingly politicized) question of whether or not harsher winter storms could be a result of a warming climate.

“I wouldn’t say that one cold or snow event would link to climate change. I just don’t think there’s enough evidence there,” Bumbaco says. “But it’s an area of research that has ramped up over the past several years, and it seems like there’s evidence on both sides.”

She says that although Feb. 9 was the first time the National Weather Service has ever issued as blizzard warning for the Yakima Valley, “I wouldn’t use this [storm] as a poster child for climate change.”

“But on the other hand,” Bumbaco continues, “our climate in Washington State has been warming. Our temperatures are going up in all seasons. And whether you look at it seasonally, on an annual basis or as a long-term trend, these sorts of events have become more usual.”

Bumbaco points to studies that focus specifically on the effects of climate change on the agricultural industry.

The University of Washington’s State of Knowledge Report from 2013 has an entire section devoted to agriculture. In this section, the researchers’ biggest concerns are related to warmer summer temperatures and reductions in summer streamflows combined with an increasing demand for irrigation water.

“In the Yakima Basin, for example, water shortage years are projected to increase from 14% of years historically (1979-1999) to 43 to 68% of years by the 2080s,” the report finds.

And while it doesn’t mention blizzards (or even snowflakes), the report does project an increase in extreme weather in the future, even under low and medium greenhouse gas scenarios.

The more recent and comprehensive National Climate Assessment reaches similar conclusions regarding extreme weather events in the Northwest.

“Extreme events, like heavy rainfall associated with atmospheric rivers, are anticipated to occur more often,” according to the Assessment, which similarly finds that: “severe winter storms are also projected to occur more often, such as occurred in 2015 during one of the strongest El Niño events on record.”

In summary, it is scientifically debatable to link an isolated weather event to the climate, as they are separate phenomena. But as our climate continues to warm, we seem to be feeling the effects.

Look up Ben Snipes of Snipes Mountain fame. Along about 1888 or so, he lost something like 50,000 head of cattle, or so the story goes. He made a lot of money herding beef cattle up to the mining areas of BC, but probably not that year.

Read Roscoe Sheller’s story “Blowsand” of his family arriving in Sunnyside the winter of 1898 during a bitter cold northeaster with blowing snow.

The skeletons of Ben Snipes’ cows were still littering the ground.

In five years they experienced two more “Northeasters” which the old timers told them lasted three days.

Sunnyside was a desert of tumbleweeds and sagebrush. Land was selling, only because of the railroad and the promise of irrigation water. As more crops requiring irrigation water are planted in the desert, there will be more concerns about enough water.

Thanks for covering the story. I didn’t hear a thing about it in my little Oregon town. Are used to live in the Yakima Valley. We had cold, we had snow, we had wind, but we never had a bunch of cows die from it!