By Dac Collins. June 27, 2019. There was a time when we didn’t have to think twice about eating a fish that was caught from the Columbia River. But thanks to decades of unchecked pollution at the Bonneville Dam Complex, some of the Columbia’s resident fish are now considered too toxic to eat.

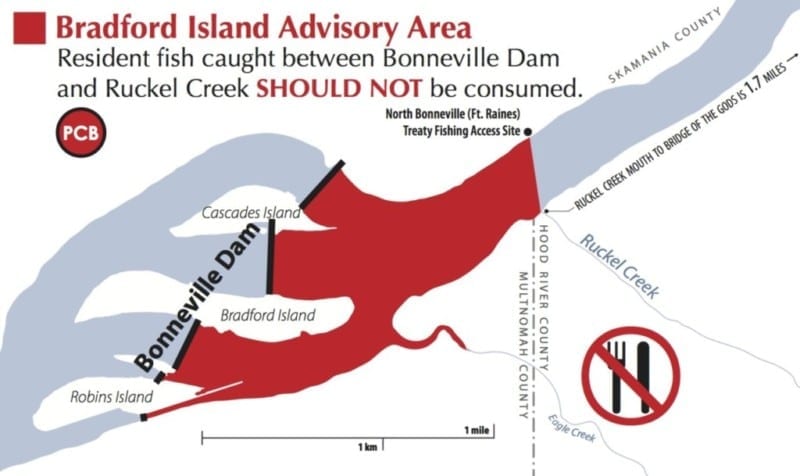

Studies have shown that the fish living between Bradford Island and Ruckel Creek contain some of the highest levels of cancer-causing PCB’s in the Northwest, and the Oregon Health Authority currently recommends that no one eat resident fish caught from this stretch of river.

Map by CRITFC

According to the OHA: “When fishing between Bradford Island and Ruckel Creek eat only salmon, steelhead, shad and lamprey. Due to chemical contamination, all other fish living in this area are not safe to eat.”

“Health effects of eating contaminated fish can include lifelong learning problems and cancer,” the OHA’s advisory reads.

Instead of looking for another place to cast our lines, however, Yakama Nation Fisheries and Columbia Riverkeeper want people to know there is another option. They can demand that the U.S. government clean up after itself and take actions to restore the health of one of the most popular recreational fishing sites in the mid-Columbia region.

“In our view, telling people that they can’t eat what should be healthy, locally caught fish is not a long-term solution,” says Lauren Goldberg, Columbia Riverkeeper’s Legal and Program Director.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“It’s not about creating zones throughout the Columbia River where it’s too toxic to eat locally caught fish.”[/perfectpullquote]

Seeking a more appropriate and thorough solution, Goldberg says that Riverkeeper will continue to stand in solidarity with the Yakama Nation in order to push for government cleanup on and around Bradford Island. She explains that Yakama Nation Fisheries has led and will continue to lead this effort, but that Riverkeeper is now doing its part to raise awareness about the issues surrounding the island.

Looking back

Located in the middle of the Bonneville Dam Complex (and within Multnomah County), Bradford Island became a literal dumping ground during the construction of the dam in the 1930’s. For decades, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers utilized the upland, northeast portion of the island (upstream of the dam) as a landfill, burying electrical equipment and other materials such as scrap metal, paint, oil, mercury lightbulbs, wires and insulators.

The landfill area is located on the northeast (far left) end of the island. Photo courtesy of Flickr

Laura Shira is an environmental engineer who works with Yakama Nation Fisheries on a number of cleanup operations throughout the mid-Columbia region. She explains that in some instances, this equipment was dumped straight into the river.

“When they sent divers down to look at some of these hotspot areas,” Shira says, “they realized that there were actually capacitors that had been dumped directly into the river.”

Many of these capacitors, she explains, were full of dense oils laden with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB’s) — oils that have now leaked out and settled into the bedrock and sediments at the bottom of the river.

Shira says the diving crew also studied some of the crayfish living on that bedrock, and found that “after the crayfish tissue results came in, the contaminant concentrations were so elevated that they wondered if the contaminant concentrations only came from the crayfish tissue or if the crayfish were also coated with the PCB-laden oils.”

And keeping in mind that crayfish are a major food source for resident species like smallmouth bass, which generally stay within a one- to two-mile stretch of river for their entire lives, it’s plain to see why health authorities on both sides of the river have raised public health concerns.

Members of the Yakama Nation Tribal Council have shared these same concerns for decades now, Shira says, but it wasn’t until after they filed a lawsuit against the Army Corps of Engineers back in 2014 that they felt like their concerns were actually being heard. That lawsuit resulted in a declaratory judgment, which confirmed that: 1) the Yakama Nation should have some input as to how the cleanup moves forward and 2) the tribe should be reimbursed by the Corps for the cleanup costs they have incurred over the years.

“Since then,” Shira says, “we feel that there’s been a big difference in how the Corps is interacting with Yakama Nation.”

“I think our first step with this lawsuit was to get meaningful engagement. And now that the Corps is, in some capacity, listening to us, we need to do a better job at engaging the public.”

Fortunately for the Yakama Nation, Columbia Riverkeeper has been more than willing to lend a helping hand on that front, with Community Organizer Ubaldo Hernandez leading the outreach and education efforts.

Moving forward

“A lot of the outreach is actually going there and talking to fishermen about what is going on,” says Hernandez.

Hernandez has also brought attention to these issues through Conoce tu Columbia, a bilingual podcast produced by Riverkeeper, and by hosting community forums throughout the Gorge. He says that by making people more aware of what’s at stake, “they will be more willing to participate and support real cleanup of the site.”

But when it comes to implementing “real cleanup”, Hernandez, Goldberg and Shira all point to an overall lack of initiative on the part of the Army Corps of Engineers. They say that 2007 was the last time that the Corps took significant actions to clean up the island.

According to the Corps website, the agency “removed the electrical equipment from the river bottom” in 2002, and in 2007 they “dredged sediment from approximately one acre of river bottom to remove PCB contamination from the environment.”

But a subsequent Remedial Investigation Report released in 2012 shows that “contaminant levels were not reduced by the dredging project.”

For Hernandez, these explanations fall somewhere between insufficient and insulting.

“To say, ‘we tried it but it didn’t work.’ Well that’s not enough,” Hernandez says. “Tell that to the people that bring fish home to their families, to their kids and their elders.”

A fisherman prepares to leave Bradford Island with a load of American Shad, which are considered an invasive species in the Columbia River. Because they are also a migratory species, shad harvested around Bradford Island are considered safe to eat by health authorities in Oregon and Washington. Photo by Dac Collins

As it stands now, Corps spokesperson Sarah Bennett says their top priority is reducing contaminant loads in the upland (landfill) portion of the island. She explains that the agency still has a voluntary cleanup agreement with the Oregon Dept. of Environmental Quality, pointing to a Final Feasibility Study that was released by the agency in 2017.

The study lists five potential alternatives for cleaning up the landfill area. The most thorough alternative would be “complete landfill excavation and backfill”, which, according to the agency’s estimates, would cost over $2 million. More moderate (and less expensive) alternatives include shallow excavation and the capping of contaminated soils.

“Since 2007”, Bennett says, “we have been working diligently alongside our technical advisory group, including area tribes, the Environmental Protection Agency, the states of Oregon and Washington, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to monitor and study the conditions on and around Bradford Island to inform our decision-making about the best course of remedial action going forward.”

And regarding the public’s ability to weigh in on the upland portion of the cleanup, she says, “We anticipate a public comment period this fall.”

Until that public comment period opens up, however, Shira reminds people that they can always get engaged by writing a letter to the Corps and voicing their concerns.

“You don’t have to be technically savvy to be heard,” she says, “and I think that the more people that can speak up about this area, and bring whatever meaning they can to it, the better.”

For those interested in learning more about Bradford Island and the current state of the cleanup, Riverkeeper will host a Bradford Island Community Forum on Aug. 6 at the Gorge Pavilion in Cascade Locks. RSVP here

I knew there was a reason my subconscious told me not to eat the salmon from the river.

But the Indian main diet is historical. We have defiled the water and the fish, and the people who live off them. So incredibly sad.