As an agreement with Canada nears, we have a rare opportunity to improve a badly outdated treaty. President Biden can help right now

Good vibrations: At the historic site of Kettle Falls near the U.S.-Canada border, rocks are thrown into the water to mimic sounds heard underwater by returning salmon. A modernized Columbia River Treaty would improve conditions to support salmon reintroduction and greater involvement of Tribes. Photo: Peter Marbach

By Joseph Bogaard. May 11, 2023. Last month, the U.S. government held a listening session on the Columbia River Treaty, a 60-year-old agreement that shapes how the United States and Canada share and co-manage the international Columbia River Basin.

The two countries have spent the last five years in active negotiations over the treaty’s future and have settled on “modernized” as the defining description for what they are working toward.

According to recent statements by both countries, an initial framework or agreement-in-principle on an updated treaty could emerge within months.

The 17th round of formal negotiations will take place next week in Kelowna, B.C.

As we approach a new deal for the future of this international watershed, we need to ensure that a “modernized treaty” is truly modern and reflects today’s great challenges and opportunities.

At last month’s listening session (click here and scroll down for recording), I had the opportunity to testify to federal agencies on the U.S. Columbia River Treaty Negotiating Team, alongside 22 other voices from across the Pacific Northwest.

The significant majority of those voices called for urgently needed improvements to a treaty that was crafted in the middle of last century. It must be strengthened in ways that reflect today’s values and prepare us for a better future.

How to fix the treaty

First and foremost, a modernized treaty must include “Ecosystem Function”—the health of the river—as a new primary purpose, co-equal to its original purposes of hydropower production and engineered flood risk management.

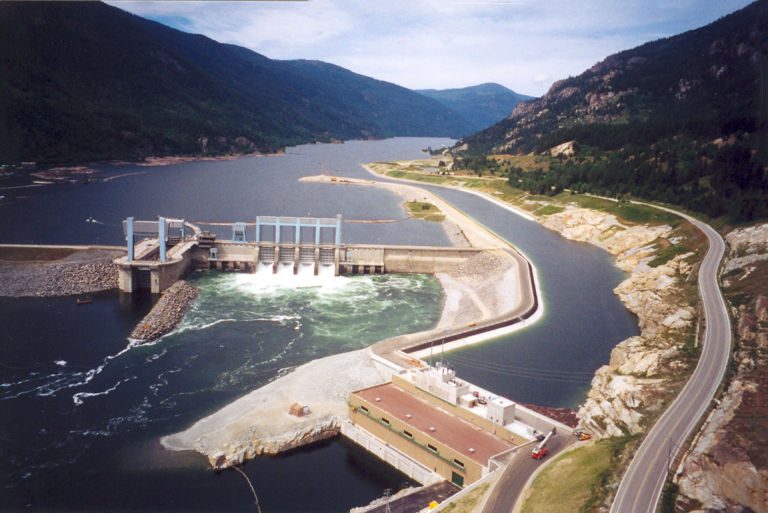

The Columbia River Treaty primarily concerns four large dams and their reservoirs in the Columbia River’s mountainous headwaters in Canada (including Northwest Montana’s Libby Dam, whose reservoir stretches across the border).

The management of these dams, which are part of the much larger interconnected hydrosystem, plays a significant role in shaping downstream river conditions.

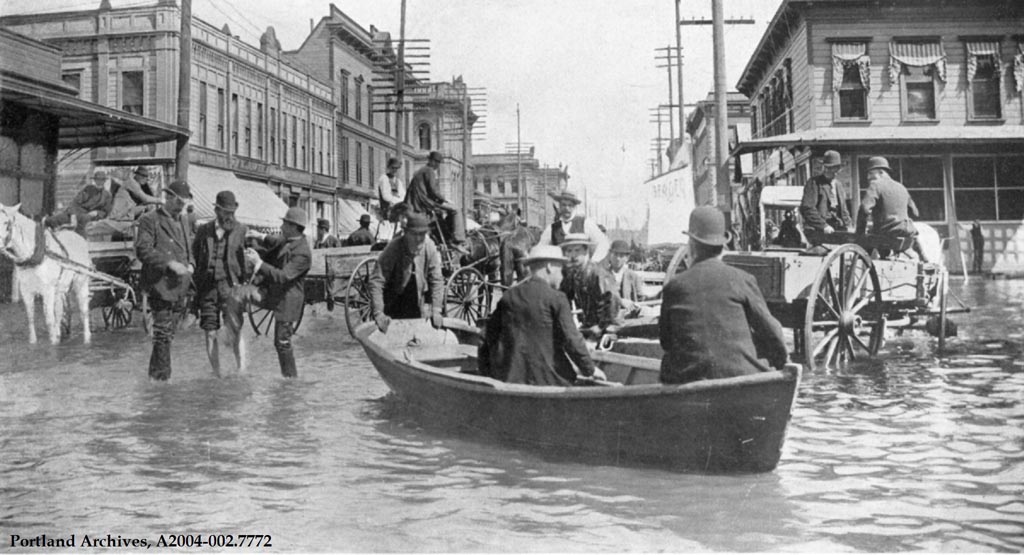

Paddle Portland: In the Great Flood of 1894, high water on the Willamette River was heightened by flooding on the Columbia. Dams and flood-risk management under the Columbia River Treaty have largely brought such catastrophes under control. Photo: City of Portland Archives

The dams also block anadromous cold water salmon and steelhead from reaching their ancestral, vibrant, high-elevation habitat. In Canada and Northwest Montana, the construction of these dams inundated nearly 500 square miles of ecologically, culturally and agriculturally rich lands and flooded more than a dozen communities, with ongoing negative impacts that persist to this day.

We now have a rare opportunity to adjust and improve the treaty—and the management and condition of the river and adjacent communities. It’s crucial for the entire watershed, and the wider Northwest region, that we get this right.

In addition to a new treaty purpose, we need to expand the treaty’s governance systems to ensure that Ecosystem Function is effectively implemented. The United States and Canada need to agree on international mechanisms to make this happen in the modernized treaty.

However, there is also a simple domestic action that President Biden can take right now using his executive authority to help us move in this direction.

Under the treaty, each country appoints an “Entity” to represent it in treaty implementation. Today, the U.S. Entity includes only the Bonneville Power Administration (for hydropower production) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (for flood control). There is currently no voice for the river on the U.S. Entity—and this must change.

Over 30 years of failure by these agencies to stop, much less reverse, the salmon extinction crisis in the Columbia-Snake River Basin makes it clear that they are unable to adequately represent the needs of the river, fish and wildlife and the communities and people that rely on it.

Going forward, we need a new member(s) added to the U.S. Entity that can ensure Ecosystem Function will be effectively represented and implemented as a new primary purpose of the Columbia River Treaty. This could be, for example, a federal agency (or agencies) with expertise and a focus on the environment, and/or Tribal nations or entities.

The current Columbia River Treaty was designed over the 1940s and 50s and ratified in 1964—before the Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act, National Environmental Policy Act, United States v. Oregon (Belloni Decision), United States v. Washington (Boldt Decision) other key statutory and legal frameworks that aim to better protect healthy, resilient ecosystems and honor the rights of this watershed’s tribal nations.

Standards for public engagement in the previous century were also significantly different—and less robust—than today. (We still have more work to do!) So it should not surprise anyone that the current treaty ignores ecosystems, contains no formal role or involvement for tribes and fails to involve the affected public. This must change.

Stop repeating mistakes

Disappointingly, a small number of voices at the Listening Session called on the U.S. government to “keep it simple,” and maintain the status quo from last century. With so much changing quickly—societal values, the importance of inclusion and justice, climate, salmon and orca populations, energy technologies and more—we need a truly modern treaty that looks forward to meet these challenges and seize new opportunities.

Decision makers from decades past chose to ignore the complexity, interconnectedness and ecological abundance of the Columbia River Basin. They tried to transform a living river and watershed into a machine.

These changes—especially the construction of scores of dams throughout the basin—have delivered important benefits, but we cannot simply ignore or wish away the often catastrophic consequences for the human and natural communities that relied—and still rely—on upon living rivers.

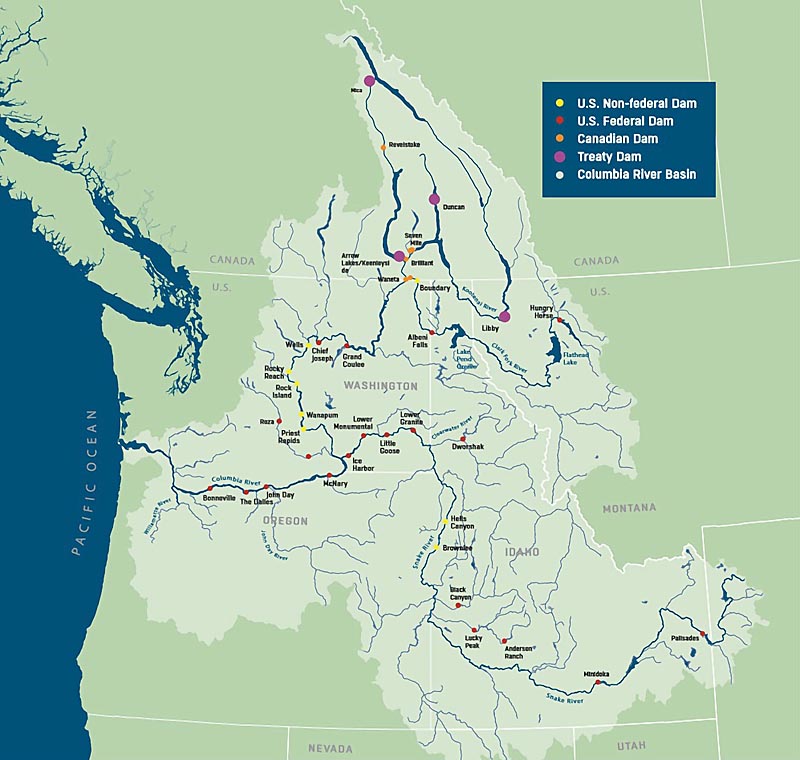

Columbia River Basin and Columbia River Treaty map from Save Our wild Salmon.

Thankfully, there were many more voices at the Listening Session calling on today’s decision makers to look into the future and craft a truly modern treaty that recognizes healthy ecosystems as a benefit, not a cost. A treaty that is prepared to respond to the pressures of climate change. A treaty that pursues robust international collaboration instead of artificially splitting the watershed into diminished fragments. A treaty that honors the rights and expertise of Tribal Nations. A treaty that meaningfully involves the public.

All this, and more, can be accomplished if the Biden administration, the Northwest Congressional Delegation and other key officials hear loud and clear from voices across our region that we need a modernized Columbia River Treaty that is genuinely modern.

A treaty of our time and our values that future generations can be proud of.

The U.S. government plans to hold another Listening Session sometime after next week’s round of negotiations. Written comments and questions can be submitted at any time to columbiarivertreaty@state.gov. To stay tuned, you can register for updates from the Save Our wild Salmon Coalition here.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to its author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of anyone else associated with Columbia Insight.

I hope we can get some benefit for the environment and the tribes out of this treaty update. Climate change and anadroumous fisheries should point treaty workers to make changes in how the Columbia River is managed.

Thanks for your letter Jurgen. I sent a contribution.

we make it about people and money. it is about the river that, even now, lives, nourishes and sustains us. will send a contribution. we live in far ne washington. what can we do to help? thanks for your work

We need that third voice during these decisions. Relying on Bonneville Power and the US Army Corp of Engineers will not result in a ‘modern’ treaty. Tribal Nations must have an equal seat at that table.