Catalyst: Days after this subadult female cougar was killed in Goldendale, Washington, the Klickitat County sheriff’s office announced its new Dangerous Wildlife Policy. Members of a 130-member posse soon joined the hunt. Photo by Alicia McInturff

Story by Dawn Stover. September 24, 2020. On the morning of August 22, 2019, Goldendale, Washington, resident Alicia McInturff heard a “godawful sound” while her husband was getting ready for work. “We didn’t know exactly what it was, but it was so loud.”

McInturff and her husband, who lived on the southern edge of town at the time, walked toward the sound and saw bushes and trees moving.

“When we got closer, we heard a growl and a hiss, along with a deer screaming bloody murder,” she recalls. A cougar was killing the deer.

She called the police and explained what was happening. Two Goldendale police officers, Klickitat County’s emergency services director, Klickitat County Sheriff Bob Songer, three other sheriff’s office employees and a volunteer hound hunter deputized by the sheriff all responded to the scene. The deer was dead before any of them arrived.

Captain Jeff Wickersham, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) enforcement captain for Region 5, which includes Klickitat County, was an hour and 40 minutes away. The sheriff’s call report says Wickersham advised that he would respond if needed, but gave the go-ahead to shoot the cougar if it was a matter of public safety.

“The police and the guys with the dogs were chasing this cougar around the neighborhood,” says McInturff, who watched the cat sprint past her, jump a fence and run from yard to yard in a panic before the police cornered it in a neighbor’s backyard and shot it seven times.

By the time Wickersham and Todd Jacobsen, WDFW’s wildlife conflict specialist for Klickitat County, arrived, “everything had transpired,” says Jacobsen. He collected biological samples for the department’s scientists and recorded the sex and age class of the animal: a female estimated to be 10 to 12 months old.

“I understand why they killed the cougar,” says McInturff. “It was right there on the edge of the field where kids walk by.” But when she called the police, she did not know they were going to kill the cougar. And she did not know that her report would stir up such strong feelings—both for and against cougars—in Goldendale and beyond.

“That’s what started it all,” she says.

Five days later, Songer, a blithe man in his seventies who was elected sheriff in 2014, unveiled a new Dangerous Wildlife Policy, saying that his office had received “numerous” complaints about cougar sightings.

He announced that he was establishing a program in which his deputies and members of his 130-person volunteer posse, which includes eight deputized hound hunters, would respond to “all reported dangerous wildlife conflicts” and would have the sheriff’s authority to use dogs to track down and kill animals deemed to be a public safety threat.

Songer had effectively declared war on cougars in Klickitat County.

WDFW’s unprecedented ‘partnership’

Until about a year ago, WDFW responded to most cougar complaints in Klickitat County. WDFW enforcement agents and wildlife conflict specialists were responsible for confirming sightings and determining whether a cougar had killed any livestock or domestic animals, or behaved in a way that threatened public safety.

They were also responsible for prescribing the appropriate response, ranging from a cougar “removal”—that is, using dogs to tree the cougar and then shooting it—to simply talking with the property owner about ways to avoid conflicts with cougars.

Relocation usually isn’t a solution, because cougars are highly territorial and will likely return to the area or be killed while trespassing on another cougar’s territory.

WDFW was low on staff in Klickitat County in 2018, when Songer first started asking Wickersham about starting his own program. Songer says he got the idea from rancher Bruce Davenport.

After the cougar incident in Goldendale, Songer decided to take matters into his own hands. On August 27, 2019, he notified WDFW: “As Sheriff, I have decided immediately to establish a program in accordance with Washington State Law RCW 77.15.245(2a).”

Pursuing cougars with dogs is illegal in Washington. But state law contains this exception cited by the sheriff: “Nothing in this subsection shall be construed to prohibit the hunting of black bear, cougar or bobcat with the aid of a dog or dogs by employees or agents of county, state or federal agencies while acting in their official capacities for the purpose of protecting livestock, domestic animals, private property, or the public safety.”

In his announcement, the sheriff stated that his department, together with its posse and special deputies, would work with WDFW but would provide the primary response to conflicts involving dangerous wildlife, and the sheriff would be in charge of the program. Later, in March 2020 testimony to the Fish and Wildlife Commission, Songer made himself even clearer: “I’m not here to ask you for permission to do something,” he told the commissioners. “I’m doing it anyway.”

When I spoke with Songer on July 31, he estimated that his staff and posse have killed 16 cougars since June 2019. Some were not known to have harmed any humans, livestock or pets.

Wildlife enthusiasts and local residents concerned about the growing number of cougars shot by law enforcement officers say these animals—which are also known as mountain lions or pumas—should not be hunted or dispatched simply because they have been spotted in an area where humans are also living. But in Songer’s view, any cougar seen in a pasture or near a home warrants a lethal response.

“My job is public safety,” he says. “Never on my watch do I want to have to come up to a house, knock on the door and tell the parents that we found little Johnny down by the river, half-eaten by a cougar.”

MORE: Wolverines break through in Cascades … finally!

The sheriff, along with many local ranchers and other residents, is convinced that cougar populations are swelling, putting public safety at risk. Scientists who study cougars say these beliefs are based on myths and misperceptions, and that indiscriminate killing of cougars is likely to make residents less safe.

Cougar advocates accuse the sheriff of usurping responsibility for wildlife management from the state. In a June 5 letter, the Humane Society of the United States called on Washington’s governor, wildlife director and attorney general “to immediately end this illegal program.” So far, though, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife has not only tolerated the sheriff’s program but referred to it as a “partnership.”

Discrepancy in reporting

In the year since Songer announced his new program, he first met with Wickersham and another enforcement officer at WDFW, and later had higher-level meetings with WDFW’s deputy chief of enforcement, wildlife program director and regional director.

“They said yes, according to the state law, that I could do [cougar removals],” Songer recalls.

The agreement, he says, was that Songer’s office would notify WDFW whenever he called out a hound hunter.

The sheriff sends WDFW copies of his officers’ reports for cougar pursuits, but WDFW officers rarely accompany the sheriff’s personnel on any of these calls. When a houndsman kills a cougar, the sheriff’s office typically leaves the dead cougar where it was killed and notifies WDFW of the location; wildlife agents can then retrieve the carcass and take biological samples. Usually they don’t.

“We also cut the ears off,” Songer says, which prevents anyone who finds a carcass from turning it into a trophy.

There are some problems with this arrangement. The first is that the number of cougars the sheriff claims his agents have killed does not match the number in WDFW’s database. By law, WDFW is required to post on its website all reported human safety confrontations and cougar sightings—a transparency measure demanded by legislators who wanted to raise public awareness of “predatory wildlife interactions.” WDFW’s public record shows no reports of any cougar incidents in Klickitat County in 2020 that ended in a removal.

Wickersham told me, on September 9, that he was aware of only one or two cougar removals this year.

The sheriff’s reports, however, show nine cougars shot by sheriff’s officers or hound hunters in the first six months of 2020.

Rich Beausoleil, WDFW’s bear and cougar specialist, was concerned when he heard Songer testify at the March 13 Fish and Wildlife Commission meeting that his office had at that point killed 14 cougars since June 2019.

“Our agency database only reflects five,” Beausoleil wrote to colleagues in a March 16 email obtained through a public records disclosure request. “Are folks aware of this discrepancy? I can’t imagine the Sheriff is overstating his removals so it begs the question if there is a law being broken.” Beausoleil noted that the discrepancy “affects our staff’s ability to consider harvest management.”

The law Beausoleil was referring to is Washington Administrative Code (WAC) 220-400-050, a regulation that states: “Any person who takes a cougar with the use of dogs must notify the department within 24 hours of kill (excluding legal state holidays) and provide the hunter’s name, date and location of kill, and sex of animal.” The regulation also requires that anyone who kills a cougar must present the pelt and skull within five days, so that an identification seal can be attached to the pelt, and the department can extract teeth and DNA samples.

In a second email, Beausoleil pointed to WAC 220-440-090, which requires that big game animals “killed in protection of private property without a permit” be reported to the department within 24 hours.

“Seems like this enabling WAC would apply to those folks having to report,” Beausoleil wrote. “I continue this discussion because [Songer] stated that if any other counties were interested in doing what he is doing, he would show them how—and this could become even more of a concern.”

Wickersham responded to Beausoleil’s email, writing that “Sheriff Songer is not bound by WAC when responding to issues of public safety nor is he bound to reporting and biological collection requirements.”

The following day, March 17, Wickersham elaborated on that interpretation, advising that public safety supersedes hunting rules and that “this is not an issue we can push, nor should we … I think it is ill advised that an email be created that even remotely suggests a Sheriff is breaking the law.”

Wickersham noted that he had met with the undersheriff the previous week “to ensure we have a more reliable system in place for documenting attacks on livestock and pets where predatory wildlife is suspected, along with timely notification if an animal is removed so information can be collected. This is a new approach and there will be continued improvement to the process, but we have buy-in from the Sheriff to make it work and improve the system.”

MORE: How Columbia River salmon are adapting to climate change

Six months later, though, sheriff’s office cougar removals still aren’t showing up in the WDFW database. The sheriff’s office is providing reports to WDFW, according to both Songer and Wickersham, but agency staff are not following up on those reports or entering them in the public record.

In many cases, sheriff’s deputies and/or hound hunters say that they are simply leaving dead cougars at the locations where they were shot, after cutting off their ears and taking photos. WDFW is not collecting data about these animals or the circumstances of their removals.

In a September 21 email to Columbia Insight, Kessina Lee, regional director for WDFW’s Southwest Region, which includes Klickitat County, wrote that the department is committed to following up on cougar removals when notified within a week.

“Unfortunately, reports are often received too late for meaningful follow-up for data collection,” she wrote.

WDFW has launched a Cross-Program Cougar Safety Team, led by wildlife program director Eric Gardner, that has as its objective to “manage cougars while being trusted to take action to help people feel safe.” Among other things, the team plans to “continue to build partnerships with sheriffs.”

Even if Washington’s laws allow sheriffs to kill cougars in situations where public safety is threatened, do they allow sheriffs to routinely deploy hounds to chase and tree cougars? Last November, Ella Rowan, a WDFW assistant district wildlife biologist based in Ephrata, raised concerns about “the potential for harassment of cougars and other wildlife.”

In an email to Lee, Rowan wrote: “I was understanding the voters of the state prohibit the use of hound handlers for cougars outside of situations identified as dangerous by WDFW and given authorization solely by WDFW and the Commission.”

The business of cougar hunting

Hound hunting has been banned in Washington since November 1996, when voters passed Initiative 655. Some 63 percent of voters statewide—and 59 percent in Klickitat County—supported the initiative, which made it a gross misdemeanor to hunt cougars, black bears, bobcats or lynxes with dogs. It also outlawed hunting black bears with bait.

Although it’s far more difficult to kill a cougar without the help of hounds, Initiative 655 did not actually reduce the number of cougars killed by hunters. In what the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife described as “an effort to mitigate the anticipated decrease in cougar harvest,” the department replaced cougar permit-only seasons with general seasons, extended the seasons from approximately six weeks to two-thirds of the year and doubled the annual bag limit from one cougar to two.

The department also created a “big game package” that allows hunters to purchase a single permit covering deer, elk, bear and cougar. Before the introduction of this package (which costs $119.50 for Washington residents), hunters had to buy a separate cougar tag, or license, to kill a cougar. With the introduction of the package, “boot hunters” who are primarily seeking deer and elk can also kill a cougar if they happen to see one. Lots of them have.

Before the 1996 ban, WDFW sold about 1,000 cougar tags a year. Last year, they sold around 57,000. Washington hunters killed about 150 cougars in 1996; in the past five years, they have killed an average of 200 cougars per year.

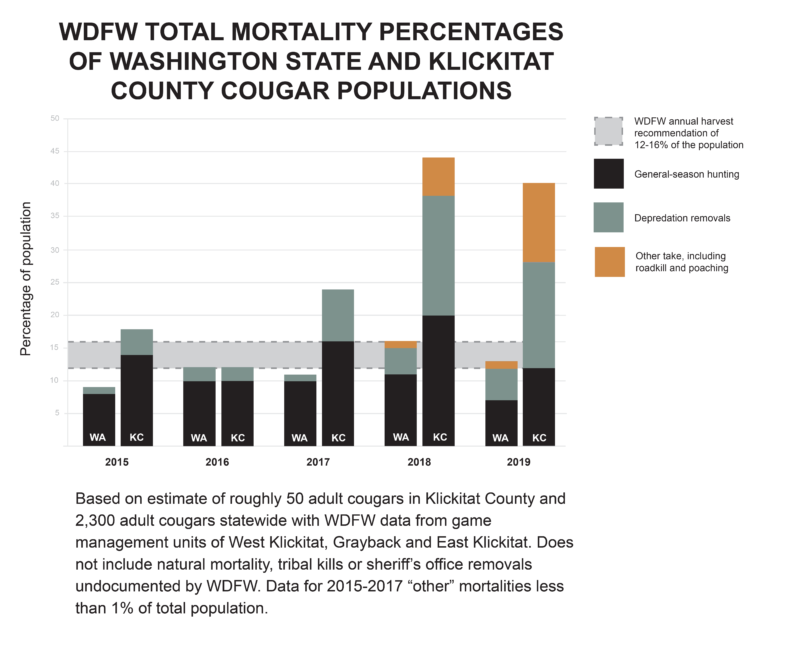

Hunting is responsible for roughly three-quarters of the cougars killed statewide by humans. However, the number of cougar mortalities attributed to other causes—depredation removals, road kills, poaching—has been rising. That is partly because WDFW has taken a more aggressive stance on human-wildlife conflicts in the past two years.

Still, the state’s stance is nowhere near as aggressive as the county’s. The fraction of cougar mortalities in Klickitat County that fall into the non-hunting category has grown disproportionately huge in the past year, owing to the surge in removals by the sheriff’s office.

In 2019, according to WDFW records, hunters killed a total of six cougars in the four Game Management Units that cover most of Klickitat County (three of the units also extend into neighboring counties). That number pales in comparison with the 16 cougars that the sheriff says his staff and deputies shot from June 2019 to July 2020.

Estimating the population of an elusive animal is tricky, but Washington has conducted extensive research on cougars for more than two decades. The state has more information about cougars than any other jurisdiction in the nation, says Beausoleil.

Researchers have conducted eight population-density studies at 10 study areas around the state. The results are remarkably consistent across the state, ranging from 1.6 to 2.8 “independent-aged” cougars (at least 18 months old) per 100 square kilometers (about 39 square miles). The average is about 2.2 cougars per 100 square kilometers, and the statewide population is estimated at roughly 2,300 independent-aged animals.

There have been no population studies focused specifically on Klickitat County, but the county’s cougar habitat is considered average, so cougar researchers might expect to see about 110 cougars in the county’s 4,931 square kilometers if the entire county was cougar habitat with plenty of cover and prey. However, only about half of the county has sufficient cover for cougars, so the county’s population is roughly 50 independent-aged cougars, Beausoleil estimates.

WDFW’s guideline for cougars is to harvest 12 to 16 percent of the population annually—or a total of six to nine animals for the four Game Management Units in Klickitat County. This harvest level is supposed to maintain stable populations and provide hunters with a good experience “while maintaining ecosystem integrity.”

It appears that the sheriff’s office alone is exceeding the harvest guideline for Klickitat County—without accounting for hunting and removals permitted by WDFW. In essence, the sheriff’s office and WDFW are double dipping.

Perception not aligned with reality

The sheriff’s new policy leans heavily on an assumption that cougar scientists say is fundamentally wrong: “Cougar and bear have over populated [sic] during the past several years because regular hound hunting of Cougar and Bear was outlawed.”

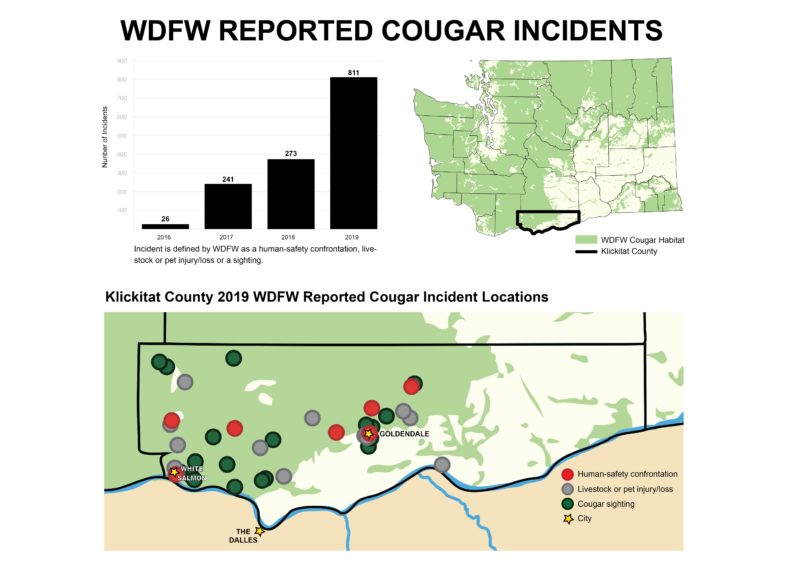

Never mind that hound hunting has been banned since 1996. The more important issue, the scientists say, is that cougar populations have remained relatively stable over the past 24 years. It’s only the complaints that have grown.

Immediately after the hound hunting ban passed, confirmed complaints spiked dramatically, rising from 247 in 1995 to a peak of 936 in 2000. Complaints then dropped back to pre-ban levels for many years, spiking again only after two fatal attacks in 2018—a biker killed by a cougar near North Bend, Washington, and a hiker killed in Oregon’s Mt. Hood National Forest, both of which were widely reported by the media.

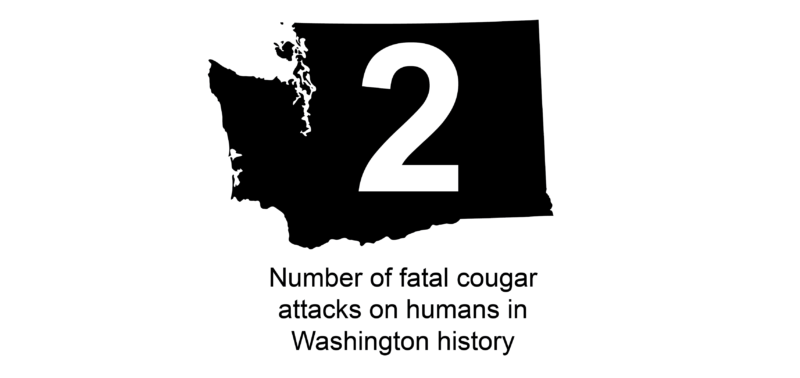

Fatal attacks by cougars are extremely rare. The Oregon hiker’s death was the first fatal cougar attack in Oregon history, and the Washington attack was the first fatal attack since 1924 and only the second in state history. There have been only 17 documented fatalities in the United States in the past 100 years. For comparison, domestic dogs kill about 28 people per year, and deer-vehicle collisions kill about 200 people annually.

In Songer’s view, cougars once restricted their movements to wilderness landscapes and did not intrude on populated areas. In the absence of hound hunting, they saw an opportunity to move closer to humans.

Cougar researchers and activists say it’s the humans who have increasingly encroached on cougar habitat, not the other way around. The human population of Washington state has grown 55% since 1990, and cougar prey—namely deer—are frequently present in areas where humans live.

“If you have a forested landscape surrounding your neighborhood, your farm, or your town, you’re going to have cougars,” says Brian Kerston, WDFW carnivore research scientist.

Studies of cougars that have been collared and radio-tracked show these animals spend a surprising amount of time on the fringes of human habitation. All these studies have found that the majority of cougars using areas with residential development never have any interactions with humans, Kertson says. “They are very secretive. They make their living staying out of sight.”

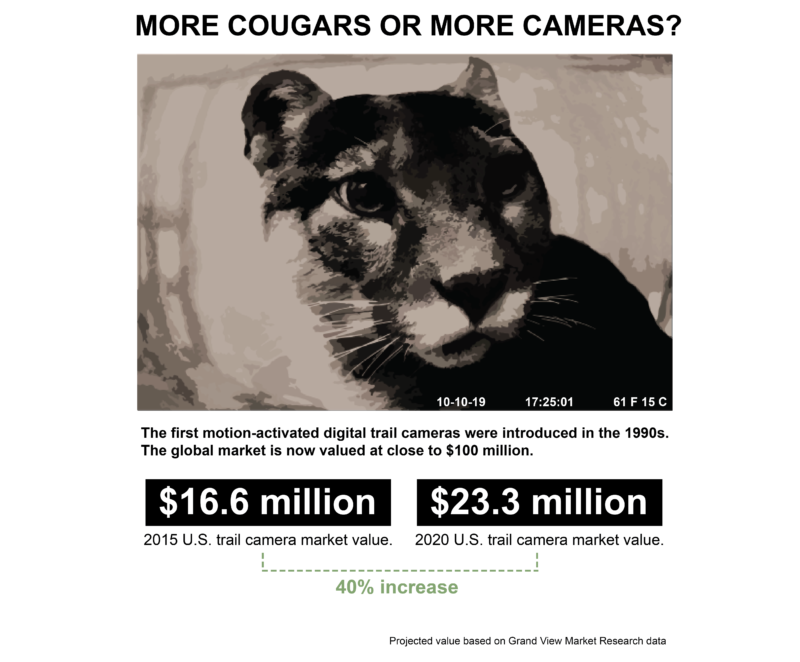

In the past, a cougar passing through a field or prowling the woods adjacent to a residential neighborhood usually went unnoticed. But sightings have soared along with the availability of inexpensive trail cameras and home-surveillance systems.

“They’re deployed all over the place,” says Kertson.

People can now monitor properties 24/7, and the images they obtain are frequently shared on social media. One Facebook page that solicits sightings of cougars in Washington, administered by an archery-supply store owner in Goldendale, has more than 11,000 members.

Although cameras have improved the reliability of sightings, more than 80% of “cougars” reported to WDFW turn out to be something else. Bobcats are often mistaken for cougars, but so are dogs, large housecats, dairy cows, raccoons, deer and other animals. Deer pellets are often misidentified as cougar scat, and dog paws leave impressions that are frequently mistaken for cougar tracks.

Even when sightings are confirmed, increased sightings do not correlate with increased population numbers, Kertson cautions. Nor, he says, do increased sightings correlate with increased livestock depredations or other human-cougar conflicts. Interactions between cougars and humans are driven primarily by the behavior of individual cats, not by population changes, his research has found.

Cougars are highly territorial animals, and every cougar population has two components: residents and transients. The resident population, comprised of adults with established home ranges, tends to be very stable and predictable. Each resident male patrols a territory that typically covers 100 to 200 square miles; within each male’s territory are two to four female cougar home ranges that are 30 to 70 square miles each. Multiple sightings are often the result of people seeing the same animal in different places as it moves across the landscape.

The transient component of the cougar population is comprised of adults (mostly males) and subadults (between one and two years old) that are trying to establish home ranges. The average cougar litter size is two to three kittens. When they reach 18 to 24 months of age, they must set out on their own. Typically only half of them survive to adulthood.

Transient cougars are “ultimately at the root of a lot of the problems,” Kertson says. These animals may be more likely to run afoul of humans because they have no territorial boundaries and tend to be less experienced hunters and less familiar with the local landscape. The roads, rivers and topography around Goldendale and White Salmon tend to funnel these dispersing cougars into developed areas.

“It takes them a little while to find their way out of town,” says Jacobsen.

Paradoxically, increased hunting of cougars can actually increase the risk of human-cougar conflicts by removing mature resident cougars, which creates a vacancy that younger immigrants will attempt to fill.

“Instead of the one male, you might get two or three that are not old enough to practice territoriality and defend a home range,” says Beausoleil.

If the sheriff’s goal is to have fewer or better-behaved cougars, his program is the wrong approach.

And if the goal is to prevent cougars from ever going near people or their structures, that’s an impossible task. There is no place in Washington that is more than 13.6 miles from any human development, a distance easily covered by a male cougar on border patrol.

Misreading ‘aggressive behavior’

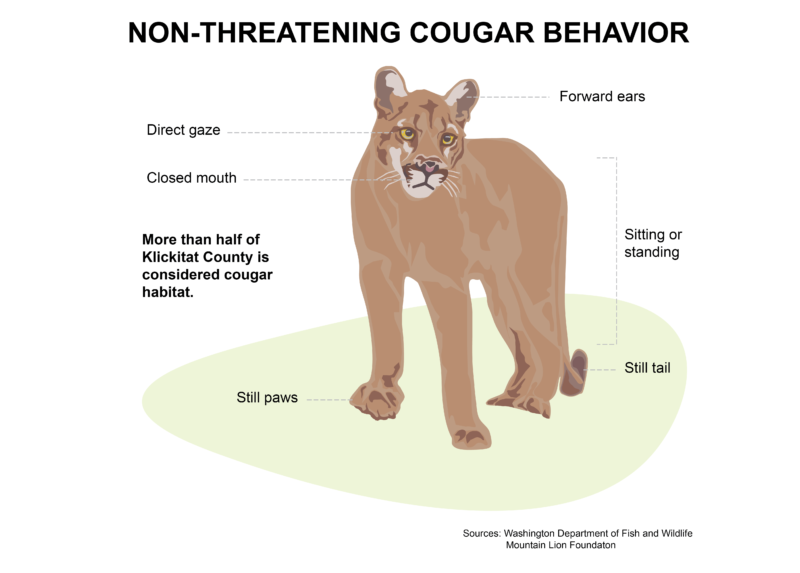

Everyone agrees that cougars do, in some situations, attack livestock, pets and, on rare occasions, humans. And some sightings reported in the past year are understandably alarming: a cougar spotted in a school parking lot, on a front porch or sleeping just outside a fenced yard. However, cougar scientists and the sheriff’s office do not agree on what constitutes a public safety threat or dangerous cougar behavior.

In his policy, Songer asserts that a cougar is an immediate threat if there is “close proximity to people or domestic pets and livestock or abnormal behaviors.” Those behaviors include “proximity to houses, people, barns or corrals,” “aggressive behaviors” and “absence of fear of humans.” A safe distance is not defined, and sheriff’s office personnel are not trained to interpret cougar behavior and signs of depredation.

Training has been offered by WDFW, Wickersham said. It has not been accepted.

WDFW’s response to dangerous wildlife complaints, in contrast, focuses on cougars that are responsible for livestock depredation resulting in the loss of an animal, behavior that constitutes an “urgent human safety concern” and any attack on a human. Mere sightings do not qualify for hound hunts or euthanizing a cougar.

“Are there incidents where the sheriff’s office has run dogs and I normally wouldn’t? Yep,” says Wickersham. “But I wasn’t there and that was their decision to make.”

If the sheriff deems a cougar to be a public safety issue, “he’s fully within his right,” says Wickersham. “I respect his perspective.”

When Songer announced his Dangerous Wildlife Policy, he claimed his office would “not be out killing every dangerous animal that is out there.”

In his commission testimony, though, the sheriff explained his program this way: “I encourage citizens to call 911, and a deputy will be dispatched … If there’s a confirmation—the deputy believes it was a cougar and not a coyote that was seen—then a hound hunter is called out immediately … and that cat will be tracked and it will be euthanized.” (WDFW advises people to call 911 only to report emergencies, and to call 877-933-9847 for non-emergency dangerous wildlife complaints.)

An analysis of recent call reports confirms that reported sightings typically lead to a hound hunt. Of 47 cougar calls made to the sheriff’s office between January 1 and July 27 of this year, only nine involved confirmed or suspected attacks on livestock or pets. None involved a direct threat to a human. In many cases, the caller reported seeing a cougar near a home or outbuilding, but in other cases the reporting party saw a cougar in a field or on a road.

Hound hunters responded to at least 30 of the 47 calls, most of which involved reported sightings of cougars, cougar tracks or deer kills. Dogs were summoned to some calls reporting secondhand or even thirdhand sightings. At least three calls involved sightings of kittens, and in two of those cases hound hunters were deployed.

Joy Markgraf, who owns 160 acres south of Glenwood, says it sickens her to hear hounds chasing a cougar. “I’m managing my property as a sanctuary,” she says, “because I want these animals to have a place where they won’t be harassed.”

Who do you love? The Sheriff is popular in Klickitat County. But so are cougars. Photo by Dawn Stover

Markgraf, who counts her four cougar sightings among the most precious moments in her life, is upset that houndsmen sometimes track cougars onto properties that don’t belong to the person making a complaint.

The sheriff claims his office hasn’t killed a cougar on property where the owner refused permission to hunt, but call reports show that deputies sometimes leave phone messages when they are unable to reach landowners before hounds cross property lines.

The sheriff’s office reports often use language describing cougars as “dangerous” or “menacing,” but rarely cite behaviors that would be considered abnormal by a cougar researcher.

“There is a misperception that seeing cougars in particular places at particular times correlates to abnormal behavior,” says Kertson.

For example, some people wrongly believe it’s abnormal for a cougar to be seen in broad daylight.

Others wrongly believe that if a cougar doesn’t run away at the first sight of a human, the cougar has an “abnormal” absence of fear. Cougars have a natural fear of dogs, because cougars evolved alongside wolf packs capable of taking down a big cat. But each cougar has a unique personality, and some are less fearful of humans than others.

Behaviors that untrained observers may perceive as aggressive may simply be cougars exhibiting curiosity, indifference or a defensive stance. Sitting and watching, for example, is a normal cat behavior.

The sheriff’s reports almost never mention any behavior that scientists would agree is genuinely aggressive, such as tail twitching or thrashing, ear flattening and vocalizing.

“People have an innate fear of cougars,” says Kertson. “They are big animals with big eyes.” When people see a cougar, they tend to interpret its behavior through a filter of fear, he says.

More intimidating: Cougars or sheriff?

Fear was on full display at the March Fish and Wildlife Commission hearing, when one after another cowboy-hatted rural resident stepped up to the microphone to call for killing more cats.

The following month, the Commission voted for an upward adjustment to the recreational cougar harvest guidelines, which will extend the hunting season in areas where both harvests and conflicts have historically been high.

In Klickitat County, the sheriff is “creating a hysteria around mountain lions and bears,” says Stephen Capra of Footloose Montana, a group dedicated to trap-free public lands.

Denise Peterson of the Mountain Lion Foundation, a national nonprofit group that advocates for cougars, and Capra visited Klickitat County in February to meet with local residents who are upset about the cougar shootings and to gather information.

Peterson and Capra also met with Songer and two of his staff, in an office decorated with photos of Donald and Melania Trump, guns and the Second Amendment. Capra says he asked Songer whether he intended to extirpate cougars, and the sheriff admitted that was his goal. (Songer told me he doesn’t remember saying he wanted all cougars killed.)

“He’s built an army to go kill them,” says Capra, who sees the sheriff’s actions as a campaign for ranchers’ votes and a way to legitimize hound hunting. “The sheriff has rallied a culture war within his own community.”

Look out: An adult male cougar surveys potential threats. Photo by Richard Beausoleil/WDFW

Songer, who has never killed a cougar himself but has eaten cougar burgers prepared by a friend (“kind of a sweet taste,” he recalls) is already at the center of several other culture wars. He is a “constitutional sheriff,” part of a group of sheriffs who have declared themselves the law of the land. (Although sheriffs are not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, state constitutions outline their duties and place few restrictions on their powers.)

Songer has stated that he will not enforce the voter-initiated state law that tightened gun-purchasing requirements in 2018, and more recently stated that Washington Governor Jay Inslee has violated the First and Second Amendments by not allowing citizens to attend church or sell firearms during the coronavirus pandemic.

The sheriff, who has spent his entire career in law enforcement, including what the White Salmon Enterprise described as a “checkered history,” is a darling of far-right groups and has appeared on conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’ “InfoWars” program. He is popular with many of his constituents. Some display signs thanking the sheriff “for protecting our liberty.”

While Songer may be popular with the public, so are cougars. In a statewide survey conducted in 2008, including more than 1,200 telephone interviews of randomly selected participants, WDFW found that 92 percent of survey respondents agreed that cougars are an important and essential component of Washington ecosystems, and that cougars have an inherent right to live here.

Conversely, 87 percent disagreed that cougars are a nuisance animal and that cougars spotted in or near towns should be killed. An overwhelming majority of all respondents (93 percent) said it is the responsibility of pet and livestock owners to secure their animals against cougar depredation.

The survey was part of WDFW’s 2010 cougar outreach and education plan, which identified Klickitat County as a “hotspot area” with a growing human population, robust cougar population and negative attitudes toward cougars.

Earlier this year, in an attempt to take a “proactive approach” to reducing human-cougar conflicts, WDFW wildlife conflict specialist Todd Jacobsen sent out a letter to residents of the Snowden and Trout Lake areas, where a lot of cougar and bear complaints have originated in recent years. He included a brochure that gave residents information and tips about coexisting with cougars, and informed them that more hunting or removal of cougars will not necessarily increase safety.

Jacobsen also gave a presentation on living with wildlife to a packed room at the White Salmon Valley Community Library in January. According to several people who attended, posse members came to the presentation and verbally harassed Jacobsen.

“There were a few people who wanted to get into specifics about cougar management,” he says.

While some Klickitat County residents are afraid of cougars, others are afraid of the sheriff and his posse, which Songer says functions as a countywide neighborhood crime watch. I spoke with a half dozen people who strongly oppose the sheriff’s cougar policy but did not want to speak to me on the record. Some have turned to organizations such as the Mountain Lion Foundation, Humane Society and Center for Biological Diversity for help.

The Center for Biological Diversity has asked people to write to the governor, urging him and other officials to “stop this abuse of power” by sheriffs. The Mountain Lion Foundation is planning to offer presentations and workshops in Klickitat County to teach people how to avoid conflicts with cougars. And the Humane Society is pressuring state officials to end Songer’s program.

‘Legal gray area’

The letter sent by the Humane Society claims the state legislature places the authority for managing wildlife solely in the hands of the Fish and Wildlife Commission and WDFW, and that the sheriff’s program is undermining wildlife management and violating the ban on hound hunting. Songer is not only “excluding, ignoring and disrespecting WDFW and its biologists” but also calling on other sheriffs to independently manage wildlife in their counties, the Humane Society argues.

“Most of the incidents [the sheriff is responding to] really are not a safety risk,” says Haley Stewart, Humane Society wildlife protection manager. “These are sightings in areas where cougars are known to live … a cougar just being a cougar.”

Thus far, the governor’s office has not weighed in on the legality of Songer’s program, but the attorney general’s office and WDFW have indicated that the sheriff is acting within his rights. In a November 22 email to Ella Rowan, the biologist who expressed concerns about cougar harassment, Mick Cope, deputy director of WDFW’s Wildlife Program, replied that the law that allows the sheriff to kill cougars “for the purpose of protecting livestock, domestic animals, private property and public safety” also allows him to use hounds.

Cope noted that no state laws define “public safety” or what it means to “protect property,” nor do they require the sheriff’s office to seek WDFW determinations about whether a situation qualifies as a public safety problem.

“It’s a legal gray area,” says Denise Peterson of the Mountain Lion Foundation.

On November 25, WDFW Regional Director Kessina Lee wrote to Songer, explaining how WDFW handles reports of dangerous wildlife conflicts. For example: “Sightings with no imminent threat to public safety are referred to resources on living with wildlife.”

Lee’s letter acknowledged the “broad authority” that law enforcement agencies have when it comes to public safety, but said “it is essential that other agencies work with us” and reminded Songer that WDFW needs “timely information sharing about responses and removals” to fulfill its obligations to manage wildlife and publicly report dangerous wildlife incidents.

“We would be concerned if removal actions compromised our ability to achieve our mandate,” Lee wrote.

Are they? In a September 21 email to Columbia Insight, Lee explained that, while WDFW manages recreational hunting at the level of local population units, it also manages cougar populations at a larger scale.

“Areas of the state with lower cougar harvest … can serve as a source [of dispersing cougars] for areas of higher harvest,” she wrote. In other words, Lee expects cougars from other counties to fill the vacancies created by the sheriff’s office. In theory that would work—unless other counties follow Klickitat’s lead.

Songer’s actions have exposed a rift between the science and enforcement branches of WDFW. The biologists would prefer that trained wildlife-conflict specialists gauge whether sightings pose a public safety risk, while WDFW’s enforcement branch is fine with letting Songer and his undersheriff make those calls.

Songer says he has “an outstanding relationship” with enforcement officers, but “maybe not so much with the biology side.”

The scientists aren’t likely to win this battle. In a 2018 survey of WDFW employees, part of the America’s Wildlife Values project, more than two-thirds of the respondents said that, if forced to choose, their agency would prioritize politics over science, and traditional stakeholders over the general public.

Coexisting with cougars

The good news is that human-cougar conflicts are mostly problems with easy solutions. The key is not to manage the cougars, but rather to manage their four-legged food.

Cougars can live in any habitat that provides cover and prey. They eat mostly deer and elk, but also prey on smaller animals.

“It is highly unusual for a cougar to kill a cow,” says Beausoleil.

Most livestock depredations by cougars involve goats, sheep or chickens that are raised on hobby farms rather than commercial ranches.

A statewide program offers compensation to commercial farmers and ranchers who lose an animal to cougars. Nobody in Klickitat County has filed for losses in the past four years, says Jacobsen.

One incident that drew a lot of attention was a weekend cougar attack on September 28, 2019, that killed five goats at the White Salmon high school, where they were part of an agricultural program for students. A cougar got into the goats’ fenced enclosure, killed four and bit the nose off one. A fifth goat was missing.

The sheriff’s office called out a houndsman, whose dogs found the missing goat but were unable to locate the cougar.

Keep out: Cougar-proof livestock pens offer a simple solution to depredation. Does Klickitat County want one? Photo courtesy of the Mountain Lion Foundation

Five days later, according to a sheriff’s office narrative, a caller reported seeing a cougar near her home on Wnuk Road, about a mile from the high school. The report speculates that “it might be the same cougar” that killed the goats.

A hound hunter was called but was unable to locate the cougar. He came back the following morning at daybreak, found the cougar and killed it.

The killing does not appear in WDFW’s public incident reports, but internal notes describe the incident as a “cougar sighting only, deer carcass found in vicinity. No livestock depredation or public safety issue. WDFW not notified or involved until after cougar was killed.”

Some locals blame the incident at the high school on a failure to properly house the goats. To protect goats and other small animals that could tempt cougars, “all you really have to do is bring these animals in at night,” says Beausoleil. “If you can’t do that, use an electric fence.”

The Mountain Lion Foundation is planning to offer presentations and workshops in Klickitat County to teach people how to build cougar-resistant pens.

“We need to learn how to live with them,” says Pat Arnold, a chicken farmer in Trout Lake who calls the sheriff’s response to cougars “cruel” and “not sound science.”

The sheriff, however, does not seem interested in conflict reduction. Songer said that telling people to take measures to secure their animals “does not go over very big.”

Although cougars will kill goats and other small animals given an easy opportunity, their main food source in Klickitat County is deer. Unfenced gardens attract deer, which then attract cougars.

A deer grazing in your front yard is “their version of fast food,” says Peterson, but cats will move on if they don’t find food available. In other words, if you want fewer cougars in town, discourage deer from loitering there.

Cougars are keystone predators that help keep deer populations in check and prevent mid-level predators like coyotes and bobcats from overpopulating.

“They’re very important to keep the balance,” Arnold says. “We should work with that system and not try to disrupt it.”

“There are so many deer in town,” says Alicia McInturff, who reported the young cougar killing a deer in Goldendale. Her dog was mauled by a deer this summer. “And she’s a big dog.”

McInturff now owns property in a rural area of the county, where she keeps her chickens in a secure enclosure. She has seen a couple of cougars from her car. She didn’t report the sightings to the sheriff.

Growing problem

Cougar advocates worry that Songer’s program will spread to other counties. Stevens County has already contracted with a houndsman to dispatch cougars when summoned.

Lethal cougar removals overseen by WDFW are going up too. From 2015 to 2017, WDFW removed about 30 cougars per year statewide. In 2018, that number shot up to 80, and in 2019 the agency removed more than 100 cougars.

“Washington is going to be our big battleground,” says Bob McCoy, who chairs the Mountain Lion Foundation’s board of directors. WDFW has become a “rogue agency,” he says, and the Fish and Wildlife Commission is not exercising sufficient oversight to ensure that cougar removals are based on science and public safety, and not simply a reaction to anti-predator groups that are also pushing for the removal of wolves and bears.

MORE: Forest Service wants to eliminate protections on large trees

WDFW has assembled a Cougar Safety Team with high-level representatives from its wildlife, enforcement and public affairs divisions to address public concerns.

“What we need is a strategic effort,” said Eric Gardner, director of WDFW’s Wildlife Program at a Fish and Wildlife Commission public briefing on cougar safety on August 1.

There is talk of conducting a new opinion survey, revising WDFW’s Dangerous Wildlife Policy and the legislation that governs public safety removals, introducing new regulations to prohibit the feeding of wildlife and including local elected officials on the newly reconstituted cougar safety team.

During last month’s briefing and public comment session, conducted on Zoom, Klickitat County resident Lynn Mason posted a written question for the commissioners: “K.C. Sheriff is indiscriminately killing cougars. What are you going to do about that?” There was no reply.

Mackenzie Miller is a data visualization consultant and graphic designer with a focus on partnering with nonprofits to visually communicate data.

This story must have been wrenching to write. Thank you for a well-researched, well-written article on this difficult subject. The graphics are very helpful, so thanks for that as well. Sheriff Songer’s policies and actions are not going to improve human, pet, or farm animal safety.

Thank you for addressing this issue. I attended the informational meeting in White Salmon and watched as a group of about 10 people verbally attack the presenter. He handled it well: polite but firmly stating they were welcome to set up a meeting with him. The interesting part of this was that like Songer, they were not interested in discussion or information. Their agenda was all that mattered. That’s not how democracy works.

It’s disturbing to learn that Songer and his posse are likely killing as they deem fit and not complying with the law. Anybody familiar with Songer knows this is how he operates. His own imaginary laws and ego come first.

I live on acreage in Snowden and live with deer, bears, cougar, turkeys, coyotes, and probably the worst offender, skunks. I follow the advice given by WDFW and have no had threatening encounters. In fact, a bear or cougar provided some critically important clean-up services after a mature deer died in my front yard. Within two days, the deer carcasses was mostly gone.

Songer is the problem, not wildlife.

Dawn, Thank you for this important reporting.

Congratulations to Dawn Stover on an excellent piece of investigative reporting. However, the cited statistic that “Domestic dogs kill 28 people per year,” taken from a 2007 study, is woefully out of date. My wife Beth & I have logged fatal & disfiguring dog attacks throughout the U.S. and Canada since 1982. There have not been as few as 28 fatal dog attacks in the U.S. since 2009. Indeed, there have been fewer than 29 fatal attacks by pit bulls alone in only one year since 2010. Total dog attack fatalities are now averaging well over 40 per year, with a peak of 57 in 2017, when pit bulls alone killed exactly 40 people. As of September 24, 2020, there have been 34 dog attack deaths in the U.S. this year, including 29 by pit bulls––a pace likely to equal or exceed the 2017 record.

Thank you for this clarification.

This was most disturbing to read. Still I am grateful that it was posted.

.r Songer just keep up the good work protecting your community you are while other law enforcement are scared to get there hand dirty I wished I lived in Klickitat county myself

A sheriff should know better WHat the hell? These animals run from humans in normal situations. Gunning them down is just plain stupidity! It’s a horrific act !!! Why is this allowed?

Great informative article but also one that also makes my blood boil. This sheriff is basically thumbing his nose at the biologists, data and all the citizens who luv these animals. When are folks, who live out West, gonna get it thru their thick heads that caring about wildlife & voting Republican just don’t go together. They go out of their way to make it as easy as possible for ppl to shoot, trap & poison all our natural predators. And sometimes, as in this case, they even do it themselves. If ppl want this brutality to stop, they better start voting blue or green and fast.

Year after year I have commented to legislative committees and the F&W Commission that research on cougars going back to the mid 1980s show that hunting cougars at the rates we have seen in WA lead to increased conflict. Dawn Stover’s 2009 “Troubled Teens” article lays out the story fairly well. A study of thirty-year’s data from British Columbia, 20 years of data from WA, and studies in other states support the fact: killing numbers above about 14% of the adult cats will lead to conflicts. WDFW ignores the science, and where the most egregious over-kill occurs, we see higher complaints. WDFW touts its use of the percentage numbers as “science,” while totally ignoring other aspects involving territoriality and dynamics of cougar society.

“Areas of the state with lower cougar harvest … can serve as a source [of dispersing cougars] for areas of higher harvest,” a WDFW manager tells us. A WDFW biologist clearly states transient cougars are “ultimately at the root of a lot of the problems.” Instead of following biologists’ recommendations, the regional managers and Olympia increase the churn of cougars on the landscape, leading to increased problems, while talking about public safety. The new cougar hunting rules introduced this year, will increase conflicts. The replaced rules were designed to provide stability in cougar populations and social structure, but where the department allowed over-kills, sometimes as much as three times the biologists’ recommendations, conflicts increased as anticipated, although at an all-time low in other areas of WA. But we can take solace, the ones that ignore science are going to form a Cougar Safety Team with high-level representatives from its wildlife, enforcement and public affairs divisions. Maybe a few low-level biologists with more than two-dozen peer-reviewed research papers and decades of studying cougars would serve us better. We that don’t need another opinion survey, we don’t need to “feel safe,” we need managers “using best science” (which the department deleted from its goals in 2011) to help keep us safe. Cougars are doing their part, we need to do our part.

This so called sheriff is a disgrace to real law enforcement officers. He only enforces laws he likes and sets up private hunt clubs for his cronies. The guy is out of control. He won’t enforce mask wearing – next time I get pulled over for not wearing a seat belt here in Klickitat County I’ll just say I didn’t “feel like” following that law. After all, that’s how our chief law enforcement officer operates.

People like this songer guy only care about their power and themselves. He’s an absolutely disgracefully, heartless, power hungry citizen that believes he is the law, so he can choose to break it. Unfortunately, he’ll do more harm than good before he is ousted from his perch. Guess his political party and you won’t be surprised as his actions. Nothing matters to these people until something bad happens to them.

More people have died from COVID in Klickitat County over the past year than have died by Cougar attacks in WA dating back what, 100+ years? So it’s not really the well being of the County residents that he’s concerned with, it’s imposing his own form of law. I’m not sure why some people lionize characters like Songer since he seems intent on placing himself above the law. I hope the residents of Klickitat County vote him out of office.

The indiscriminate killing of cougars under the false claim that they represent a Public Safety Issue is unlawful. There is NO public safety issue regarding cougars in Klickitat County. This is Songer’s attempt to circumvent the laws governing wildlife enforcement and conservation. He is an embarrassment to those of us who respect law enforcement, the 2nd Amendment, and wildlife. What a joke. Remove him from office. He is a disgrace.

Why did they kill a cougar for eating a deer? That’s what they’re supposed to do. Why would you call police for seeing that? If you hate animals then live in the middle of a city, really simple.

I’m not usually one to chime in on this sort of thing, but felt a perspective was missing in this discussion. I don’t hear anybody discussing factors about why the cats are in town now more than in the past. I’m a hunter, and have been my whole life. I believe it is a fair say that I spend more time in the woods than most people. I’ve been hunting for about 30 years in this county, and have seen some changes in woods. It was a common thing to see evening herds of 60+ deer between Lyle and Goldendale in the 80’s and 90’s. Sometime in the 2000’s that changed to groups of less then 10. I used to rifle hunt deer in the hills, but have transitioned to archery hunting in mine and neighbor’s yards because that is the only place I find deer anymore(and I look year round). In my first 20 years in the woods I’d never seen a cougar, and only one bear for that mater(rarely saw sign too). In the last 5 years I’ve seen 3 cougars, 6 bears and more signs of cats and bears than deer. Something is off when you see more predators than prey. All within a 30 min walk from my kid’s school. Not saying they are endangering my kids, just that they are there more commonly now than in the past. I do think there is a wildlife mismanagement issue to blame, but think the focus is wrong. Most of the GMU’s in our county have traditionally high deer harvest rates. It appears that WDFW has used 3 point or better with drawn tags to manage the populations and limit the amount of deer taken. Though it does limit harvest rates it has another undesirable affect. We take a significant portion of the adult mature strong members of the deer population in a relatively unnatural way. The week get taken by the predators. Those that are left, it seems, are hiding in people’s yards. The cats are just following them in. From what I’ve seen around the edges of my town’s valley, I’m confident there are at least 6 cougars that live within 2 miles of my home(I’m more or less in a town too). We’ve even had them in the yard on a rare occasion. I don’t buy the traditional isolated huge territory theory, it isn’t what the woods around me tells me. Maybe that was the way it used to be, or maybe those that formed the behavioral theory of these animals didn’t have all the factors and were generally wrong. I’m here to tell you folks that these are much more social creatures than traditional profiles give them credit for. I cut tracks on 4 different cats within 1/2 mile of each other on the same day last fall, so I find it hard to believe there are only 2.2 cats per 39sq miles. Of coarse this was within 2 miles of my home, so maybe this is swaying things. I do think it is worth considering altering deer quotas such that some of the mature animals make it and help encourage populations that live outside of town. Another potentially overlooked factor is how weed control efforts have removed many bushy cover spots where deer used to bed between fields(not to mention game birds). Come on people, this is a total chicken and the egg problem. The chickens(cats) are the byproduct of mismanagement of the eggs(deer). If we enable the eggs to be in the woods, the chickens will follow them out of town. We need to focus on deer populations and deer habitat management. I believe focusing on developing mature well spread deer populations is our best path to defusing the cougar issue we are facing.

Thank you for considering another point of view that may be a path towards a solution we can all get behind.

thirty years ago there used to be a forest north of goldendale on the simco’s, not now no thermal cover for the deer, grew up hunting there used to see tons of deer not now

Songer is a criminal, NOT a sheriff. He ignores the laws that he is supposed to enforce. He’s a typical, modern-day Republican: laws don’t apply to him, an ignorant, fascist, anti-US Constitution, anti-American, seditious, criminal, tRump TRAITOR, and it is time he was treated as such. He should be immediately fired, and arrested for abuse of power and ignoring/breaking laws. He should spend the rest of his truly worthless life in prison, preferably with “BAD COP” tattooed across his forehead, just to bring justice home.

Rick Siegfried, I have to agree with you 100%. This here and the one I had read in local newspaper hasbeen very disturbing. I live in the mountains and I have come upon a few cougar. They have done no wrong. They ran the opposite direction. That man that was wrongfully elected for sheriff???? Wow, icsmt believe that anyone would agree to such stupidity. Maybe there shouldn’t a posse put together to stand between the wildlife and this posse that So get put together. Can only imagine who would be on such a thing. Leave the wildlife alone. They are only trying to survive as we all are. They are being run out and their land taken away as was the natives long ago. Who says you can choose who or what lives and what or who does. . Of what I have seen so far this so he is a mockery to this county. Feeding his ego with stupid publicity. I second that firing him. Leave the cougars be. And don’t bring those dogs into this wilderness. I was told that hunting dogs has been banned from this area. This subject sickens me.

I have read the article and comments and I see good and bad points that everyone is expressing. However I can see one point that no one has brought up. We can and do keep making people, but we can’t make more land. We are developing in their territory. We are the predator’s. I haven’t heard of one problem in the world, that isn’t caused by over population. Just Think about it before you pull the trigger, is this really the right solution? Isn’t there something else we can do? Think about the balance of nature.

[…] September 2020, Dawn Stover and Columbia Insight reported on a war on cougars being waged in Washington’s Klickitat County. Despite more than two years of public outrage, […]

I wish mrs Stover and everyone criticizing the sheriff’s actions a very pleasant having your pets and children mauled and eaten by a wild predator.