Researchers are concerned about new threats to populations, especially in Washington

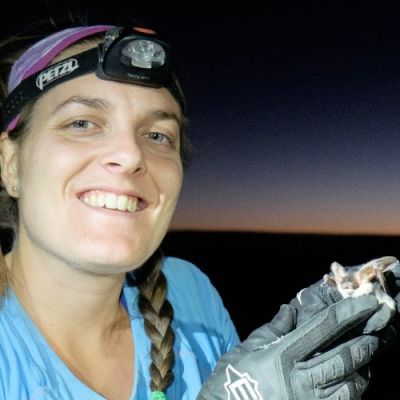

This silver-haired bat was studied as part of a Bureau of Land Management monitoring program in Oregon’s Lakeview District. Photo: Alyson Yates, BLM volunteer

UPDATE: On Sept. 19, 2025, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife announced that the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome in bats has been detected in the state for the first time. Samples analyzed by U.S. Geological Survey confirmed the presence of the fungus in guano collected from a bat roost at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park near Astoria in Clatsop County.

By K.C. Mehaffey. August 17, 2023. Studying bats is tricky. For many species, the people who study them don’t even know where their colonies are located.

But one thing is certain: new threats—including white-nose syndrome and mortalities from wind turbines—are taking a toll on bat populations across Washington.

Bat experts say we may not know until it’s too late whether the losses from these new threats are significant enough to cause serious population declines.

Government agencies and nonprofit groups are working to find answers as planning for more massive wind farms takes shape and white-nose syndrome continues its incremental march across the state.

Of the two newest threats, bat experts say both are equally concerning.

White-nose syndrome is a fungal disease often fatal to hibernating bats.

The fungus can grow on the nose, wings and ears of an infected bat during winter hibernation, giving it a white, fuzzy appearance. Once the bats wake from hibernation, the fuzzy white goes away.

Even though the fungus may not be visible, it invades deep skin tissues and causes extensive damage.

The disease does not affect humans, livestock or other wildlife.

In Washington—where white-nose syndrome was first detected in 2016—there have been 190 total confirmed cases of the disease or the fungus that causes it in individual bats, according to Abby Tobin, lead biologist for bat species at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

That’s practically insignificant compared with an estimated 4,900 annual bat fatalities from wind turbines in the state.

But Tobin notes that, compared to looking for carcasses under wind turbines, it’s much harder to find a bat that may have died from the disease after emerging early from hibernation (one of the disease’s side effects).

It’s hard to know how many bats have died from white-nose syndrome mostly because biologists don’t know where to find them so they can test for the disease.

Range of disease

When white-nose syndrome was first discovered in Washington, about 30 miles east of Seattle, the closest known cases were in Oklahoma.

“Frankly, it took us off-guard. We were not expecting to find the disease,” says Tobin.

Seven years later, Washington is still the only state west of the Rocky Mountains to have white-nose syndrome, although other states in the West are starting to find the fungus through regular surveillance of bat colonies.

Tobin says Oregon, Idaho and British Columbia all conduct comprehensive monitoring, similar to Washington’s. An interactive map shows one location in the southeast corner of Idaho, and one in south-central British Columbia where the fungus that causes the disease has been discovered. None have been detected in Oregon.

Abby Tobin. Photo: WDFW

But the disease’s impact in the eastern U.S. has been dramatic.

According to a recent report by the North American Bat Conservation Alliance, the risk of extinction for bats is rising.

“Experts now estimate that 52% of bat species in North America are at risk of populations declining severely in the next 15 years,” the report states.

White-nose syndrome is considered among the top threats, since millions of bats in North America have died from the disease since it was first detected in New York in 2007.

According to the report, 12 North American bat species are susceptible to the disease, and three species—little brown bats, northern long-eared bats, tricolored bats—suffer a 90% fatality rate once they’re infected.

Tobin says four species in Washington—the little brown bat, long-eared myotis, Yuma myotis and fringed myotis—have each been affected by the disease, and have seen fatality rates as high as 90%.

But these species tend to hibernate in places that are sometimes inaccessible.

“Here in Washington, we do not have the ability to see bats hibernating, so we don’t end up seeing that white nose, or fungal growth,” she says. “What we see is wing damage. That is the clinical sign we are looking for when we are out in the field.”

Researchers still aren’t sure if the disease is spreading more slowly in the West than it did in eastern states, or if it’s just tougher to find because bats in the West are more spread out, and their colonies are smaller.

Washington continues to conduct active surveillance, using WDFW biologists and partners from other government agencies and nonprofit organizations to collect samples from bats or their roosting areas.

This spring, two new counties were added to the list of locations where the disease or its fungus have been located. Ten of 39 counties now have the disease, or the fungus that causes it.

The state is also asking the public to notify WDFW not only when they see a sick or dead bat, but also to help identify known hibernation or roosting areas so they can increase surveillance.

Attracted to turbines

Other wildlife—such as migratory birds—are affected by wind turbines.

But none are more threatened than bats.

That’s because certain bat species aren’t just hit by turbines as they pass by, but—for unknown reasons—bats are actually attracted to them.

“They approach them and spend a lot of time flying around them. Even when they’re spinning, they don’t appear to know they’re at risk,” says Cris Hein, lead researcher for the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s wind and wildlife program.

According to a report by the Renewable Energy Wildlife Institute, an average of 6.35 bats in the United States die for every megawatt of wind energy produced each year. With about 140 gigawatts of annual wind generation, roughly 889,000 bats die annually in the United States.

With wind energy projected to grow 5- to 10-fold over the next two decades, bat deaths from wind turbines are on course to skyrocket.

“So how do we address that problem at that pace and scale? It’s really concerning for everyone involved, including the industry,” says Hein.

Not enough is known about where the susceptible species spend time to address the problem through siting.

Looking for clues: Abby Tobin tests a bat for white-nose syndrome. Photo: WDFW

One strategy is to reduce wind turbine speeds, which has been shown to mitigate the impacts.

Another is to curtail wind generation when the bats are most at risk—from mid-July through mid-September.

Although effective, the downside of curtailment is that the turbines aren’t generating energy, and from an energy company’s perspective, that’s not acceptable, says Hein.

“I don’t understand all of the economics of wind, but I’ve been told there are really fine profit margins,” he says.

Power purchase agreements put wind companies in the position of guaranteeing certain amounts of energy, so asking them to curtail production means they may not be able to meet those agreements.

“I think in some cases, the industry would be willing if they didn’t have certain constraints on them,” he says.

For now, researchers are trying to find other ways to keep bats away from wind towers.

Acoustic deterrents—such as high frequencies—are being tested, with varying success.

New efforts are also going into targeted curtailment, which would automatically stop turbines when certain conditions are met—like when there’s a bat in the vicinity.

“A lot of studies are underway or almost finished, so we should know more by this time next year,” says Hein.

Why care about bats?

According to the North American Bat Monitoring Program, bats are important indicators of healthy ecosystems because of their sensitivity to changes in the environment.

They have an average life expectancy of 20 years, and have just one or two pups each year—making it difficult to recover a population that suffers rapid decline.

All of the bat species in the Northwest eat insects and play a critical role in controlling pests.

Nationwide, it’s estimated that bats save more than $3 billion annually by preventing crop damage and pesticide use. In other parts of the world, they’re important for pollinating plants and dispersing seeds.

Bats are the second-most diverse order of mammals, with some 1,400 species worldwide.

The United States has 47 species. Eight species or subspecies are listed as endangered, and one is threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

None of Washington or Oregon’s 15 species of bats is listed under the ESA.

However, the little brown bat—which is highly affected by white-nose syndrome—is under consideration for listing by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which expects to make a decision next year.

Like much of the country’s wildlife, bat populations are already suffering from a loss of habitat. For bats, deforestation, mining, agricultural land conversion, urbanization and pest management are the major causes.

Climate change is also a huge threat to bats as food sources could become limited.

Extreme weather events, drought or severe heat may force changes in roosting, foraging, reproduction and migration.

Not all bad news

It’s not all bad news for bats in the Northwest. A few things appear to be working in their favor.

White-nose syndrome and wind turbines are largely affecting different species of bats, according to Hein of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory.

While many species of bats can be carriers, hibernating species are much more susceptible to sickness and death from white-nose syndrome.

Conversely, migrating bats that don’t hibernate are significantly more likely to get struck by the blades of a wind turbine.

“There is some overlap,” says Hein. But by and large, the same species aren’t getting hit with two significant new threats at once.

The other good news is that white-nose syndrome appears to be spreading in the West much more slowly than it did in the East, according to Tobin, the WDFW biologist.

One possible reason is that eastern hibernacula—where bats hibernate—are much larger, often containing thousands of bats.

Known hibernation locations in Washington often have fewer than a dozen bats.

The silver lining for migratory bats is that researchers have already found ways to vastly reduce bat mortalities.

Hein notes that 80-90% of bat deaths from wind turbines occur in a two- to three-month period: during migration in late summer and mating in early fall.

Although most wind generation companies aren’t yet using it as a tool, wind curtailment at night during those months could significantly improve survival, he says.

Race for solutions

For biologists tracking white-nose syndrome in the Pacific Northwest, the solution may lie in medical treatment.

Tobin says Canadians developed a probiotic cocktail that inhibits the growth of the fungus.

“They got through several phases and they’re now into field trials,” she says.

Since white-nose syndrome still hasn’t been confirmed in British Columbia, Canadians are working with Washington state to test the cocktail’s efficacy.

Additionally, a vaccine with antigens that will elicit an immune response in bats has been developed by the U.S. Geological Survey.

“We are the first western state to participate in that effort,” says Tobin.

The hope is that some way to help bats weather this disease will be developed before white-nose syndrome spreads across the West.

The solution for researchers who want to see some kind of mitigation for the impact of wind energy on bats is a little more complicated.

Hein describes the situation as almost a Catch-22.

“It’s not in anyone’s interest to wait until a species becomes listed, but oftentimes, that’s the only time action occurs,” he says.

“In my conversations we have regarding bats and wind, everyone recognizes this—the industry, conservationists, researchers—all recognize that it’s not in our best interest to continue on the same path we’re on. But it doesn’t make it any easier to make a change to the status quo.

“We’re a little paralyzed, I think, knowing we need to do something, but the solution’s going to cause pain.”

Researchers have made headway in finding solutions. Now, it’s a matter of whether it will be possible to implement these solutions at a scale that protects bats and allows us to produce renewable energy.

Excellent! Detailed and explains well the problem and the variety of challenges being faced to find a solution. I was particularly interested in the information about bats and their interaction with wind turbines.

I really hope an antigen can be found. I love seeing bats gobble

up the mosquitoes!