A career wildland firefighter explains why firefighters are growing disenchanted with their profession and calls for the creation of a Federal Fire Service

Walking away: For overburdened wildland firefighters “burn-out op” has taken on new meaning. Photo: Bré Orcasitas

In September, wildland firefighter Bré Orcasitas posted a story on her personal blog sounding an alarm about firefighters leaving their jobs due to extreme stress, hazards, professional mismanagement and maltreatment. Her explanation of what she and others see as a gathering crisis—albeit one difficult to fix statistics to—swept through the national firefighting community, drawing attention (though not yet decisive action) at top levels of federal agencies responsible for land management and firefighting. Columbia Insight asked Orcasitas for permission to republish her article. She agreed on one condition—that we run her story in its entirety, so that the full breadth of issues impacting this critical work force could be presented. —Susan Hess, Publisher

By Bré Orcasitas. November 11, 2021. You may have noticed that wildland firefighters have been in the news lately. This is mostly to do with the fact that many are resigning from their positions due to low wages, among other things.

Although this comes at a time when many professions nationwide are advocating for higher wages, the great exodus that is occurring amongst the ranks of the wildland firefighting population is on a catastrophic trajectory because of what it will mean for wildfire response moving into the future.

Introduction to wildland firefighting

In the beginning, wildfire was fought by anyone willing and able to run to the edge of the forest to try and stop it before it engulfed their town. But it’s come quite a long way since the early 1900s.

This profession provides an easy parallel in many ways to active-duty military. Operating within a chain-of-command and requiring high levels of physical fitness, firefighters hike, parachute and rappel into chaotic and dangerous job sites while spending extended periods of time away from their homes and families.

Night out: Wildland firefighters typically improvise accommodations. Photo: Bré Orcasitas

The work itself is mostly miserable; masochistic even. From early spring to late fall firefighters in the West hand their lives over to the “fire season.” While away on 14-to-21-day assignments, firefighters work 16-hour shifts hiking in rugged terrain, digging in the dirt and running chainsaws while carrying heavy packs and regularly ingesting smoke, only to go home for two days of R&R before reporting back to their crews to repeat the same cycle for upward of six-to-eight months, on average.

“R&R days” afford just enough time to do laundry, re-pack gear and make a brief appearance with family and friends before returning to the field.

Most firefighters will accrue 800-1,200 hours of overtime each fire season, which basically equates to “If you’re awake, you’re working.”

All this time invested doesn’t even speak to the eastern fire season, taking place the other half of the year.

MORE: Wildfire researcher offers answers to our most burning question

Of course, there’s something to love about wildland firefighting. Otherwise, people wouldn’t dedicate their lives to it.

The wildland fire community has always been able to recruit and retain firefighters by instilling the core values of Duty, Respect and Integrity; also, by placing a high value on the developed camaraderie amongst crewmembers.

Wildland firefighters don’t shy away from hard work.

Quite the opposite really—firefighters take pride in the fact that not just anyone can do this job. Traditionally, those who can endure the physicality and unconventional lifestyle rarely walk away from it.

This is what makes the current situation so concerning. Though difficult to quantify with precise figures due to the way federal job levels are classified, federally employed wildland firefighters with 10-20 years of service are making the hard decision to transition out of wildfire in droves and it isn’t because they’ve lost passion for the job.

It’s because the job is breaking their spirit, their families, their hearts and their bank accounts.

Breaking their spirit

Although wildland firefighting has evolved over time, the wildland firefighting organizational structure has not. This essentially means doing exponentially more with less.

Fire managers are completely overtasked, overstressed, overburdened and left wanting for basics like administrative assistants and full staffing so they can actually focus on managing their local fire programs.

Further down the ranks, firefighters on the ground are dealing with increasingly volatile and unpredictable fire behavior and for much longer periods of time each year. There is certainly no backup for those on the fireline who become completely exhausted and run down from working long shifts and sleeping in the dirt before rising to do it all over again.

The physical toll that firefighting takes on the body very obviously has long-lasting and often untold effects.

Even on what should be days off, fire managers act as duty officers (a 24-hour responsibility, almost entirely unpaid) constantly responding to calls, emails and texts. Similarly, fire crews can be required to be on-call to respond within two hours (also an unpaid expectation).

Simply put, there is no “off switch” for firefighters until Mother Nature allows it.

Breaking their families

Absence makes the heart grow fonder until it doesn’t. Having a partner/spouse in wildfire essentially means being alone for more than half the year, every year.

Home alone: Firefighters often miss family gatherings, holidays and birthdays. Photo: Bré Orcasitas

For those who have a family, the burden of being a single parent for the majority of each passing year can turn from frustration into resentment, especially if you’re stuck living at a remote duty station. With firefighters averaging four days at home and “off” per month for six-to-eight months each year, you can imagine the strain it creates due to a lack of presence or reliability.

When children are involved, the partner/spouse’s career is adversely affected due to a lack of accessible and/or affordable childcare during summer months.

Not surprisingly, the divorce rate within the wildland firefighting community is high due to such a relentless and unbalanced work schedule. Building a life with someone who leaves for work in the morning that may not come home that evening, or 14-to-21 days from then, or never again, is not an easy circumstance to endure.

For fire families the reality is the job comes before everything else, day in and day out, year after year.

Breaking their hearts

This job kills people. There has not been a single recorded year to date that hasn’t resulted in at least one firefighter fatality during the fire season.

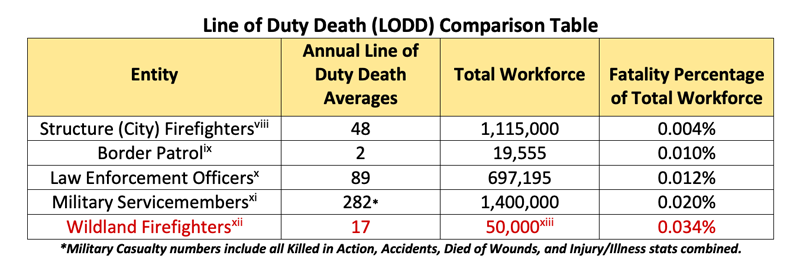

On average, approximately 17 wildland firefighters are killed each year in the line of duty.

Beyond that, many more sustain catastrophic injuries while working on wildfires, resulting in either serious rehabilitation or permanent disability. When either of these two occurrences happen the hoops that must be jumped through for the most basic care and dismal benefits is an absolute disgrace.

To be a member of the wildfire community means that you’re part of the fire family. It also means that people you know and care about will die and you might be standing right there trying to save them when it happens.

Table by Bré Orcasitas

Every single shift on a wildfire has the potential to end someone’s life, including your own. The longer anyone stays in this profession the more people they will outlive.

As firefighters move through their careers these traumatic instances pile up, leaving many to battle anxiety, depression and PTSD; pushing them toward heavy drinking, substance abuse or worse.

Unfortunately, rates of suicide are extremely high in the wildfire community. Due to lack of education about the effects of trauma and how to cope with it, many firefighters resign due to experiencing crippling triggers and severe panic attacks associated with previous traumatic incidents on the fireline.

The most offensive aspect regarding the high rate of Line of Duty Deaths is that federal wildland firefighters are not even classified as “wildland firefighters,” but instead “forestry technicians.”

This begs the question: how many forestry technicians must die in the line of duty each year before rightly being regarded as wildland firefighters?

Breaking their bank accounts

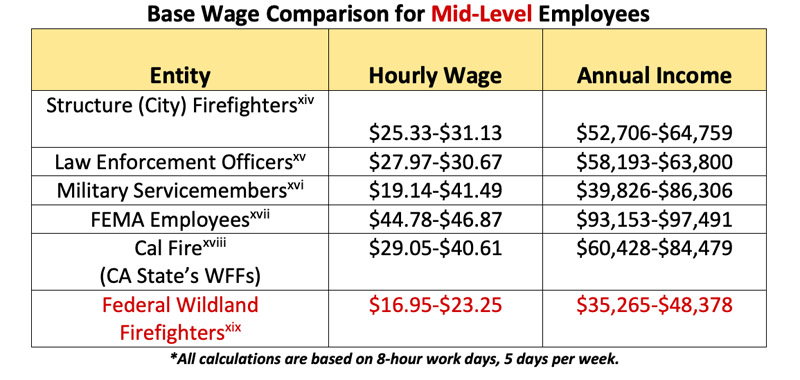

The above table clearly shows that wildland firefighters have the highest fatality rate for Line of Duty Deaths when compared with similarly dangerous professions. The table below shows base wages associated with comparable professions.

Table by Bré Orcasitas

Imagine this scenario: you’re working a standard eight-hour shift at your office and just as you are about to leave for the day your supervisor requests that you work an additional eight hours. After working 16 hours you attempt to go home again only to have your supervisor say, “You’ll be needed at work first thing in the morning and because your commute is too far you’ll have to sleep under your desk.” For the eight hours that you’re sleeping uncomfortably under your desk, away from your home and family, you are not getting paid.

Welcome to the world of federally employed wildland firefighters.

Fire organizations like Cal Fire pay firefighters for 24 hours, “portal-to-portal” while on assignment. Yet federally employed wildland firefighters (the majority of WFFs nationally) are paid up to only 16 hours per day.

Bucking up: Despite hazardous duty, firefighters receive insufficient support services. Photo: Bré Orcasitas

Beyond low wages, federal wildland firefighters are lacking in any sort of critically needed resource programs or allowances for assistance with housing, childcare expenses, uniforms, mental health programs or relocation allowances such as a military service member might receive.

Seasonal firefighters—a sizable portion of the workforce—don’t even receive year-round healthcare or retirement benefits.

In the same vein, when it comes to on the job injuries the current worker’s compensation system oftentimes denies firefighter claims, leaving firefighters to either spend time in lengthy appeals processes, use personal insurance or pay out of pocket for expensive procedures in order to get healed and get back to work.

Even worse, there have been countless instances in which severely injured firefighters have been flown via Life Flight helicopter from the field only to later be presented with bills from the hospital charging them for all the incurred costs.

By the time paperwork gets straightened out and the confusion settles it usually costs the firefighter an incredible amount of undue stress when they’re already trying to recover from severe injuries.

Further damage comes to the firefighter when they learn their credit is completely ruined from the prolonged debt dispute.

All this for being injured in the line of duty.

The reality

The reality is that wildland firefighters have been pushed well beyond their breaking point for far too long. For decades they have operated within a dysfunctional system and are completely worn down from the endless stream of sacrifices.

And now they are walking away.

To make the excruciating decision to leave their brothers and sisters on the fireline, to leave a career they love, for the sake of self-preservation or to save what’s left of their personal relationships, is no small action and it is not going unnoticed within the fire community.

So, who will replace them?

Hover craft: Firefighters attach a longline for cargo as it hovers above ground too soft for landing. Photo: Bré Orcasitas

It may sound dramatic to say that these firefighters are irreplaceable, but here’s why that is a mostly true statement:

Experienced wildland firefighters understand the effects that fuel, topography and weather have on fire behavior and strategize accordingly to keep people out of harm’s way.

They can cut down burning trees with chainsaws, safely lead a crew of 20 people into a fully active fire, manage the complexities of a burn-out operation around a community, recognize and alert other firefighters when they are in a compromised situation, attach cargo to the bottom of an aircraft as it is hovering above them, rappel off the side of a helicopter, parachute out of a plane and into a fire, operate and troubleshoot engines and pumps, read maps and navigate terrain, identify different fuel types and understand how fire will react in said fuel type.

They can manage fires five-to-500,000 acres in size, manage budgets, reconcile spending purchases and navigate mountains of paperwork. Experienced firefighters know what LCES, SA, AAR, IRPG, DBH, ICS, PPE, LAL, IAP, ERC, CTR, IMT, RH, POI, SEAT, VLAT, AGL, TFR, ICP, UTF, UTL, WUI, SOP, GACC, NIFC and ELT all stand for.

If you were to ask a rookie firefighter to fill their crew captain’s position or develop a strategic plan to contain a complex fire, they’d be the first to tell you they don’t have the training or experience to do it.

Typically, it takes several years as a trainee to achieve firefighting qualifications and sometimes even longer to gain admittance to the necessary classes associated with those qualifications.

There are no shortcuts.

It cannot be understated that replacing experienced wildland firefighters with rookies is not a viable option. Retention is absolutely crucial for this profession and for public safety. Let me repeat that: retention of experienced wildland firefighters is absolutely crucial for this profession and for public safety.

Retention is imperative, especially when factoring in the high percentage of firefighters due to retire in the next five to 10 years.

Protection service: Hotshot Justin Romero consults a homeowner during the Taylor Creek Fire in Oregon’s Rogue-Siskiyou National Forest, 2018. Photo: Kari Greer/USFS

And yet there is already a severe shortage of middle leadership within the wildfire community because of the great exodus.

This means on wildfires nationwide firefighters are currently filling roles that they are unqualified for because there is no other option, while other positions are left “unable to fill.”

It’s only going to get worse if things don’t change.

We are progressing into a new era where people are much less willing to put their lives in jeopardy for meager pay merely because they feel a sense of duty. Not to mention the pool of recruits is already shrinking at a rapid rate due to less interest in jobs that require physicality—you can’t put out wildfires without boots on the ground.

These are but a few reasons why retention within the workforce is imperative.

Ultimately, however, the ramifications of the great exodus can be distilled to two sobering realities:

- The number of firefighter injuries and fatalities will begin to increase as a direct result of the lack of experience/knowledge in the workforce

- Firefighters will eventually end up having to decide which fires to staff and which to allow to burn due to a lack of qualified resources to staff them.

We are witnessing deeply invested firefighters who love their work leave the ranks. This leaves one to wonder how easy will it be to recruit new firefighters into a profession that systematically deters people rather than incentivizing them?

The fixes

A major part of the problem is that wildland firefighters are a largely invisible workforce, meaning the issues plaguing them have been invisible as well.

Although problems are many, here are some solutions for the most concerning among them. If the intent is to keep federal wildland firefighters from continuing to leave the ranks in large numbers, these require swift action.

- Increase wages to reflect the hazardous environment of the profession as well as the specialized skill sets required to do the work.

- In order to re-stabilize the workforce, offer re-hire bonuses and incentives to wildland firefighters with middle-management level (and higher) qualifications.

- Adjust work-to-rest schedules to provide time for appropriate physical/mental recovery between fire assignments. This might mean increasing crew sizes to create availability rotations.

- Address the shameful lack of resources by using military allowances as a template to create sustainable situations for firefighters and their families, thereby increasing retention. This includes dual-career firefighting couples trying to start families.

- Provide comprehensive trauma education and easily accessible mental health services.

- Immediately alter the current presumptive illness legislation for firefighters so that it includes wildland firefighters, finally addressing the long-term effects of hazardous exposures within the work environment.

- Issue additional Nomex clothing and provide safety protocols to lessen the potential for dermal transfer of toxins through the skin.

- Classify “forestry technicians” as “wildland firefighters.”

- Pay fire managers for 24-hour duty officer responsibilities; pay firefighters when they are required to be on-call for two-hour response times.

- Create administrative assistant positions for all high-complexity fire programs.

- Immediately restore “transfer of station” allowances.

- Establish a higher wage for wildland firefighters who are qualified EMT/paramedics.

- Enhance the Line of Duty Death benefits, bringing them to an appropriate level while also offering memorial services for contracted firefighting resources.

Establish a Federal Fire Service

Implementing the above solutions would address immediate needs.

But the most logical long-term solution is to carve each fire program out from its respective land management agency and create a standalone Federal Fire Service.

Currently, the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service all attempt to coordinate between themselves and then, still, state and county entities (depending on geography).

Mounting problem: National coordination is needed to fight fires in the 21st century. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography.com

The fragmentation and competing priorities of multiple land management agencies coupled with supervisors at the highest levels in the chain of command without fire experience and/or education creates unnecessary complexities for firefighters on the ground.

Having a federal fire agency would set a foundation, allowing for the flow of change to continue through the state, county, contract and volunteer entities. From there a Federal Fire Service could begin developing sorely needed infrastructure, such as regional fire hubs, using military bases as a model.

As wildfire seasons continue to intensify and extend each year, the only reasonable solution is to have a federal agency dedicated to appropriately managing fire on the landscape in order to restore forest health and help slow the ferocity of the mega-fires this country has been experiencing as of late.

For a frame of reference, the 2007 Moonlight Fire in northern California was considered large at 65,000 acres and a cost of $31 million to contain. Today, the Dixie Fire in California is still burning at approximately 960,000 acres with a price tag hovering around $592 million; at its height 6,550 firefighters were employed to contain it.

Call to action

What this all boils down to is that the toll this profession takes on firefighters and their families is too much, and it has been too much for far too long.

Have their backs? Wildland firefighters increasingly feel without allies. Photo: Leda Kobziar/Univ. of Idaho

Wildland firefighters are done asking decision-makers to hear their pleas—they have formally reached their breaking point.

If the aim is to keep entire forests and communities from burning to the ground it’s well past time for the powers that be to act because firefighters have already begun taking action; one resignation letter at a time.

You can click here to learn about pending legislation that supports wildland firefighters and show your support with this quick action.

This sounds so much like the tale of ICU nurses right now. As the workforce shrinks due to Baby Boomers retiring and Millennials not yet filling those spots, tiny Generation X has had it. American without ICU nurses or wildland firefighters would be a very scary place.

The pay thing is easy. Work your shift, fight the fire till it’s contained, what ever the hours are, 16,24,72,etc. then pay for the rest period, and go on to next regular shift. The rest work ratio is crap. We worked and rested on the clock for 26 seasons and had one of the best fire containment records in the country. The fires don’t sleep, initial attack shouldn’t, and you should stay on the line until it’s contained. Project fires should have 16,24 shifts with paid rest periods.

My husband is a man who loves and thrives on the challenges of wildland firefighting. In 2020 he pursued his dream of becoming a smokejumper. Normally he works as a forester for our state. For 2 fire seasons, they gave him a leave of absence to allow him to smokejump, then return to his job here. When he requested to continue that in 2022, he was refused. He has exceeded the max hiring age for a federal permanent employee, so most likely will be unable to return next season.

Completly ignors 12 to 15000 private contract firefighters who perform 50% of the large fire suppression

Yes they are a great resource and need the same consideration, plus they own and maintain all of their own equipment, plus pay for all training for the firefighters.

Contractors are just that, guns-for-hire. You’re hired help and the deeper in the pot the agencies dig to fill gaps, i.e. PL 4 and 5, the poorer the quality of contractors. I am sick of showing up as an agency engine just to be told I’m the only agency resource on the division and therefore am “in charge” of the four bagger crews. Had to order an excavator to feed a chipper last year due to a surface-shitting contract crew not having the sense to not shit on the brush we’d cleared. Fleecing of America is what wildland fire contracting is.

Great article! As a former federal wildland firefighter, I agree that many changes are needed in the management of the firefighting community. I left wildland firefighting after 8 years of firefighting because I didn’t agree with how things were being managed, with safety & hazard pay. When I voiced my opinion at the time there was no response from upper management. Wildland firefighting is a tough job and there is no room for inexperience. Retain the experienced firefighters and treat them well!