Commercial harvesting was eliminated for 2025. Will the ban be extended in 2026?

Up for grabs: Over-harvesting of wild huckleberries, an historic First Food for Pacific Northwest Tribes, has caused the Forest Service to re-think picking regulations. Photo illustration: Nicole Wilkinson

By Steve Lundeberg. January 29, 2026. Nine months after announcing a moratorium on commercial huckleberry harvesting, the Gifford Pinchot National Forest wants to gauge public sentiment regarding how well the 2025 ban worked.

On its Facebook page, the forest has posted links to a feedback form and a news release explaining its desire to “hear about your 2025 huckleberry experience.”

“Great year. Even better than years past since commercial picking wasn’t allowed,” wrote one commenter.

“Best year ever!” added another.

While providing argument that the pause may have been a step in the right direction, “great” and “best” aren’t entirely accurate descriptions of a Pacific Northwest resource that’s been under pressure for more than a century.

The Gifford Pinchot National Forest encompasses 1.32 million acres along the Cascade Range’s western slope in southwest Washington and includes the 21,000-acre Indian Heaven Wilderness, home of the legendary Sawtooth Berry Fields.

Named for the first director of the U.S. Forest Service, the forest is bounded to the north by Mount Rainier National Park and to the south by the Columbia River.

Prior to the moratorium—whose announcement came amid lobbying from tribal nations, forest users and local government officials to address dwindling huckleberry numbers, enforcement limitations and disputes among harvesters—the Gifford Pinchot had been the only national forest still allowing the large-scale, commercial harvesting of huckleberries.

The blues are still blue: Huckleberry, not to be confused with its blueberry relations. Photo: Jurgen Hess

Perspectives gathered via the feedback form “will help inform decisions about whether and how to offer a commercial huckleberry program for the 2026 season and beyond,” said forest spokeswoman Amanda Kill.

The Forest Service is using multiple methods to make people aware of the survey, Kill said, including postcards and flyers that have been shared with various stakeholders and partners.

Huckleberries, which can sell for up to $200 a gallon, are a relative of the blueberry. They remain an important traditional food for the region’s Native American Tribes, under whose stewardship the berries thrived for millennia.

A series of developments following white settlement, though, including 100-plus years of forest fire suppression and prohibitions on cultural burning, have eaten away at habitat for the roughly one dozen species of huckleberries native to the Pacific Northwest.

A popular ingredient in consumer products ranging from lip balm to ice cream, from wine to honey, huckleberries can’t be cultivated, meaning supplies are limited to what grows in the mountains.

“There are no domesticated varieties,” said Stephen Cook, a University of Idaho professor who studies huckleberries. “We can produce plants that grow in a greenhouse, and we can outplant them, but it doesn’t matter what we do, when we outplant them they die within three or four years. Very seldom do they flower.”

Tribal rights, picking limits

An 1855 treaty gave the Yakama Nation the right to hunt, fish and gather food, including huckleberries, throughout their ancestral homeland, whether on or off the reservation that had been created for the Yakama. It didn’t take long, however, for the federal government to begin falling short of honoring the treaty.

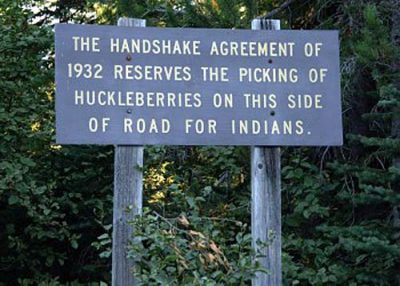

During the Great Depression, thousands of white huckleberry harvesters descended upon the Sawtooth fields, leading in 1932 to what’s known as the Handshake Agreement: 2,800 acres of the Sawtooth fields would be reserved for Tribes during each summer’s huckleberry season.

The agreement, codified in the forest’s cultural resource management plan in 1990, prohibited non-Indian harvesters from picking huckleberries east of Forest Road 24.

A 1932 council between the Yakama Nation and Forest Service resulted in a loose agreement, later codified, designating part of the Sawtooth Berry Fields for exclusive use by local tribal peoples. Photo: USFS

At about the same time, the Gifford Pinchot’s permitting system for commercial pickers went into effect. In 2024, the last year before the ban, a commercial harvester could purchase a two-week permit with a 40-gallon limit for $60, or a season-long permit with a 70-gallon limit for $105.

Personal-use pickers, who are not affected by the ban, also need a permit; it’s free and is good for up to three gallons per year.

The forest sold more than 900 permits in 2024 and says that annual harvests range between 50,000 and 70,000 gallons.

“In the last 10 years it’s been really bad,” said tribal picker Elaine Harvey, a member of the Kah-milpah Band of the Yakama Nation. “Thousands of commercial pickers take the berries before we can get there; they clear it out.”

For the Tribes, harvesting doesn’t begin until after an annual huckleberry ceremony in late July or early August, and unlike commercial pickers who use “rakes”—tools that look like a cross between a comb for grabbing berries and a dustpan for collecting them—tribal harvesters pick with their fingers

“They used to wait till Tribes had had their ceremonial feasts, but now people are just going out there to gather berries,” said Brigette McConville, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and a Columbia Insight board member. “The rakes are damaging to the huckleberry bush. If commercial picking is allowed again, they should ban the use of the rakes.”

“I don’t have data, but rakes have to do some damage,” added Cook. “People who are concerned about them have a right to be.”

Misunderstood berry

Another concern is that while huckleberries have been culturally important for thousands of years and economically significant for more than 100, they continue to pose questions that science struggles to answer.

“New starts are almost always associated with stumps of some conifer, but we don’t understand pollination for huckleberries,” Cook said. “We don’t know that insects are truly necessary for pollination activity. That leaves us in a quandary: How do we protect or restore something when we don’t even understand how it reproduces?”

Botanical mysteries aside, the reevaluation of commercial harvesting on the Gifford Pinchot that began with last year’s ban seems like a good place to begin.

Huckleberry hounds: The fall picking season typically runs from late August into September. Photo: Discover Lewis County

Harvey said the influx of commercial pickers from Seattle, Portland and even California had become a free-for-all with virtually no regulation.

Over the past two decades, McConville said, commercial picking simply devolved into a “disrespect of the resource.”

“In the last 15 years they’d been harassing us, intimidating us, siccing dogs on us, bringing weapons against us,” said Harvey, referring to commercial harvesters. “Women and elders have been scared to go up and pick alone, and we never let our children run in the forest like I did as a kid. Last year we felt safe to camp, safe to pick, safe to let the kids run free. There were actually berries on the bushes for us to harvest. It was like the clock went back to a time when it was peaceful.”

Peace and commercial picking don’t have to be mutually exclusive, said McConville, who has on occasion purchased commercially harvested berries.

“If I don’t have time to get out there and pick, I don’t mind paying someone for the time they put in, the fuel, the food, the man-hours,” she said. “But it’s fair to have a stricter policy, and the Forest Service should have more employees to patrol and check how people are gathering, check their permits. And there should be some education component to the permitting process, an understanding of the berries’ importance to native people.”

Determining if, when and how to offer commercial huckleberry harvesting in the future is all part of the current feedback gathering effort, said Kill.

The first decision will cover what happens this year. The Forest Service is in ongoing discussions with partners, interested parties, Tribes and the wild foods industry. Kill invites people following the huckleberry issue and other Gifford Pinchot National Forest topics to sign up to receive email news updates.

If commercial picking is allowed, it should all be by hand and only after the tribes have their share. Plus,it should be limited in number and charged a lot more for a permit. I have had these people completely devastate my family’s favorite places to pick. Very sad.

Commercial huckleberry picking should be permantly banned, I have noted in the last 20 years or so that more & more commercial pickers are descending on the forest and depleting large areas of berries. I have noted that the commercial pickers pick the berries sometimes before they are ripe and use rakes on the tender branches that damages the plants growth.

Huckleberries can not be grown commercially because of the special relationship the plants have with the microiza in the soil where they grow.

I used to work for the Forest Service so I was witness to the hoards of greedy commercial pickers out there taking all the berries from the indigenous people and the locals who have a tradition of picking a gallon or so of huckleberries for personal use each year.

Leave the berries for wildlife. Many species rely on them for nourishment.

Leave the berries only to the first naation people who harvested them for millions of years. They are entitled to the fruit and should enjoy it. We have taken so much from the first people that it is about time we see things their way.

Steve, thank you for this article! At the elevations where huckleberries grow, Mount Adams has sustained extensive large wildfires since 2008. This has reduced many different food sources for wildlife, making the huckleberries more important than ever as a food source for wildlife, as well as a First Food for the Yakima nation. In particular, more black bears have been showing up in Trout Lake in recent years looking for food. The raking does lots of damage to the huckleberry bushes and should never have been allowed at all. Poor oversight and stewardship by USFS let things get out of hand. The picking ban was long overdue and much needed. I hope the ban on commercial picking becomes permanent. Thank you to those at the GPNF who made it happen!