The “gloom” of the political climate has forced youth-oriented conservation organizations to change tactics

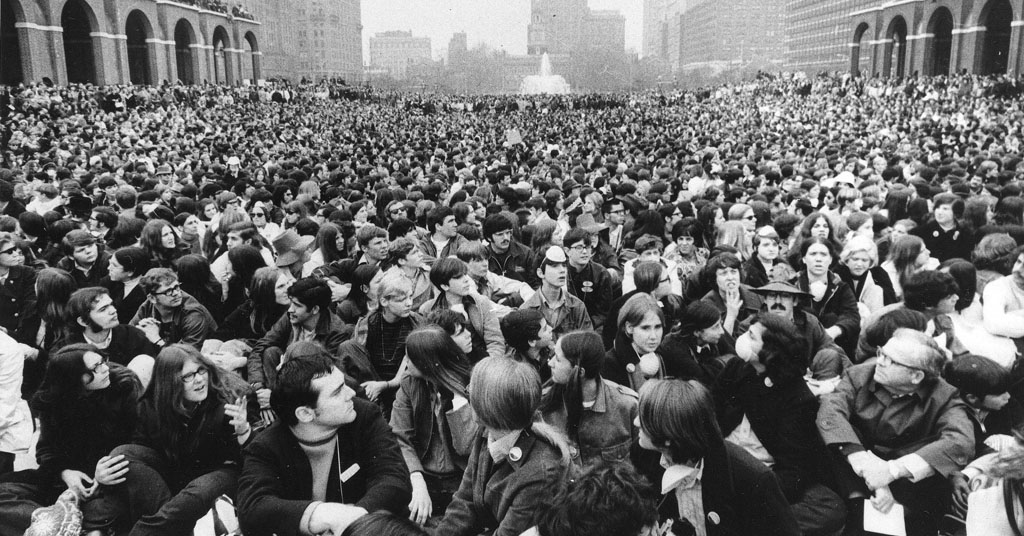

Young push: An estimated 7,000 people jammed Independence Mall in Philadelphia during Earth Day activities on April 22, 1970. Who’s carrying the torch today? Photo: AP Photo

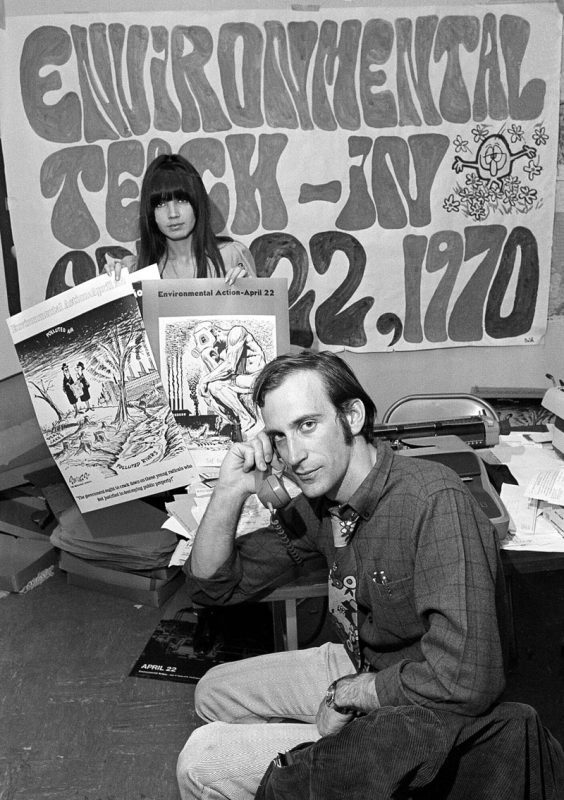

By Erica Browne Grivas. January 8, 2026. A high point of the environmental movement of the 1960s and ’70s was the establishment of the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. Inspired by the tactics of Vietnam War protestors, university students and other young people were instrumental in that and other social and legislative victories that laid the foundation for many contemporary conservation organizations and programs.

But political forces of today are different than those faced by activists even 10 years ago. To respond to them, environmental groups that appeal to younger people are adopting new tactics.

Youth participation in environmental causes may appear to be less robust than in the past—cynicism about the authoritarian behavior of the federal government might be affecting that—but in many ways it has simply transformed.

Galvanized by Greta Thunberg’s Fridays for Future and a Sunrise Movement-led sit-in at the U.S. Capitol in 2019, the national climate movement attracted hundreds of thousands of protesters.

That wave of activism, which brought thousands of young people into the national, youth-oriented Sunrise Movement, has since subsided, leaving behind more strategic, experienced organizers.

“After the 2024 election, I realized that legislation alone wasn’t going to be the answer for us anymore,” says Bailey Burk-Convery, a 27-year-old organizer with Sunrise Movement PDX. “Sunrise has this very clear mission and three-year plan that really spoke to me coming off of rapidly consolidating authoritarian government.”

The movement blends social justice, community care and local action. Organizers channel energy into tangible outcomes, from cafeteria composting in schools to community building.

“The urgency of this present time creates a different imperative not just for youth but for our society in general,” says Tami Darden, co-coordinator of Our Future, which supports student-powered change in high schools across the state.

“Grassroots organizing, collaboration and unifying become all the more important because there’s not a lot of federal funding going toward these.”

And, she adds, young people “know that that action is past due. Way overdue.”

Local legislation, UAW, cookies

Despite growing pessimism about the federal government, organizers are still pushing for legislative reform, often at a local level.

Since 2019, Sunrise, which only accepts members under the age of 35, has sprouted chapters across the country, called for a Green New Deal, lobbied for policy change and put forth its own candidates.

“We are far more experienced at engaging with policymakers and community members in productive ways, and now focus on deeper, longer-term and more specific issues, such as increasing heat wave shelter, making the existing climate policy organs in our city work and preparing our members for natural disasters,” responded a 23-year-old Sunrise Corvallis representative via email who asked not to be named.

Local impacts are evident in Oregon. Sunrise Corvallis helped elect two members to its city council last year.

In 2025, Oregon youth activists, including Sunrise PDX organizers, pressed the Portland City Council to demand oversight of Zenith Energy’s operations in the region, earning a procedural win when the Oregon Court of Appeals restored the Land Use Board of Appeals’ jurisdiction to review Zenith’s 2025 Land Use Compatibility Statement.

Bailey Burk-Convery. Courtesy photo

When President Trump called Portland a “war zone” Sunrise countered with humor, inspiring others.

“The issue most energizing to young people right now is by far opposition to fascism,” says the Sunrise Corvallis representative. “Young people want to see a kinder, juster society and the myriad cruelties of this era are energizing them to fight for a better society.”

“Recently, Sunrise National has shifted priorities with the understanding that climate legislation doesn’t happen under authoritarianism,” says Burk-Convery.

This expresses itself in different ways, many of which blend environmental activism with other issues. Under the banner of ecological concern, young people are organizing against ICE, against transphobic and racist policies pursued by the Trump administration, against campus bigots and against the genocidal treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli state and the United States’ support of those policies.

Sunrise is working toward a general strike in 2028 aligning with the United Auto Workers.

The first step? Building a climate of compassion and community.

“A general strike takes a lot of community care,” says Burk-Convery.

She leads community awareness meetings where one of the first asks might be to make cookies for 10 of your neighbors.

How big, how focused?

According to Burk-Convery, Sunrise PDX has 40 to 50 active members, and has helped set up five other hubs in the Portland metro area in high schools and colleges.

Otherwise, it’s difficult to gauge the size of youth-oriented environmental organizations, or make comparisons to the large, public demonstrations of the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.

The national Sunrise Movement doesn’t appear to release membership data, choosing instead to focus on the group’s “reach.”

“People my age haven’t seen the U.S. political scene stable enough to trust it.”

The national Sunrise Movement website has posted just one news article in the past year, an un-bylined jeremiad about Trump authoritarianism. Its headline: “To win on climate, we must crush fascism.”

Prior to that, it posted about Luigi Mangione’s 2024 murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, attempting to connect that act to environmental issues.

Its published organizational “movement timeline” ends in 2023. It’s most recent online published “win” dates to 2022, though its website does include a post about the organization’s endorsement of Zohran Mamdani, who won the New York City mayoral election in November 2025.

The national Sunrise Movement office in Washington, D.C., has not responded to Columbia Insight’s inquiry about current membership numbers or activities.

Taking it to schools

Our Future works with high schools to promote student-led change with committees on topics from waste reduction to climate justice, says Darden.

Students apply for one-year internships as regional leaders in the topic of their choice.

Lily Yao. Courtesy photo

Siri Kovi, a senior at Portland’s Westview High School, says watching other youth climate groups succeed motivates her to keep pushing for change in her own community.

Active with Our Future for four years, she serves on the Youth Board of Partners for Sustainable Schools, Our Future’s overseeing organization.

She looks forward to more collaboration in the movement connecting disparate climate change clubs and youth groups—work Our Future is already pursuing.

Lily Yao, a regional leader and student governor in Eugene, says the 2019 global climate walkouts were a pivotal moment for her in sixth grade.

“I experienced collective action around an issue I really cared about for the first time,” she says.

Working with Oregon Educators for Climate Education (OECE) to help advance Oregon’s Climate Education Bill was one of her “most meaningful experiences.”

“We collaborated on community outreach, wrote emails to legislators, submitted testimony and met with lawmakers in person,” says Yao. “Thanks to these collective efforts, the bill passed on June 16, 2025.”

Taking youth seriously

Beyond juggling school and emerging careers, young activists must contend with skepticism from adults who underestimate their capabilities, says Darden.

“Students are capable of a lot more than they’re often given credit for in terms of having ideas that could be utilized,” says Darden. “I’d like to see policymakers taking them a little more seriously and integrating their thoughts into decision-making processes can really grow what’s possible.”

“People my age and younger haven’t necessarily seen the U.S. political scene in anywhere stable enough to really be able to trust it,” says Burk-Convery. “If you’ve been around long enough, you know what a functioning government in this country looks like. We don’t really have that frame of reference. So, we’re thinking, ‘How can we change things? How can we make it better?’ Not, ‘How can we go back to the way it was before?’”

Calling all youth: Dennis Hayes, head of Environment Teach-In, Inc., the organization that coordinated activities for Earth Day, in the group’s Washington D.C. office on April 22, 1970. Photo: AP Photo/Charles W. Harrity

Building credibility is a challenge. Yao says that the more informed students are, the more weight their opinion will have.

“We need to engage in the systems that guide decision-making, whether that’s contributing to policy conversations or showing up through civic responsibilities like voting,” she says. “Our perspectives are taken more seriously when we are informed, involved and present in these spaces.”

“Focusing a lot on collective power and hope for a future has been huge,” says Burk-Convery. “At least for me, it’s a very important way to not get stuck in the gloom of the current moment.”

Describing Israel’s treatment of Palestinians as “genocidal” is ludicrous. Does the writer of this article even understand what that term means? Israelis have certainly grossly mistreated and even murdered Palestinians but describing what has occurred as genocide is false and utterly disgusting. Learn what words actually mean before using them.

The Convention on Genocide’s definition: Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as:

… any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

—?Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2[9]

While Israel may have initially responded to being attacked, their escalated actions quickly became what is defined as genocide of a group that was subject to apartheid living conditions.

Not only a fascinating topic, but EXCELLENT development and writing. Thank you! More please!