A new AI art project illustrates the “unseen impact” of decades of effort to preserve the national scenic wonder

Beacon Rock: The area near the famed Gorge landmark was the site of a proposed subdivision in the early 1980s and was primed for further development. This AI photo imagines the impact of commercialization that never happened. Image: Friends of the Columbia Gorge

By Chuck Thompson. January 9, 2025. Imagine your next drive through the Columbia River Gorge.

Just east of I-5 along Washington State Route 14, passing Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge, you gaze not at the existing, wide-open bird habitat along the Pacific Flyway (a migratory bird path extending from Alaska to Patagonia), but upon the rusting silos and stark warehouses of an industrial park.

Further east, you stop to climb Beacon Rock. Instead of the majestic view of the Columbia River you’re accustomed to, however, a cluster of multistory office buildings dominates the vista from the top.

Crossing into Oregon via the Bridge of the Gods at Cascade Locks, you double back west to take in the glorious scene looking toward Washington from Crown Point. You get out of the car and look across the Columbia River at … a sprawling subdivision. In that L.A.-to-San Diego way, houses, strip malls, chain stores and commercial development have obliterated any distinction between communities from Vancouver to Camus to Washougal.

Cape Horn Overlook: The farmlands below Cape Horn (today, left) on the Washington side of the Columbia River Gorge are located 30 minutes from the Portland-Vancouver area and, but for federal protection, would have been susceptible to commercial pressure, including industrial development (imagined, right). Image: Friends of the Columbia Gorge

These views aren’t real, of course.

But they might be, had the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act not been passed by Congress and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1986.

The act drew boundaries for a 292,500-acre patchwork of public and private lands and charged the U.S. Forest Service with implementing a management plan in partnership with the newly established bi-state Columbia River Gorge Commission.

At the time highly controversial, that piece of federal legislation saved the Gorge from runaway development, safeguarding its royal views and environmental health.

This is the message that a new AI art project released by Friends of the Columbia Gorge in December hopes to convey.

Created with AI technology, realistic “crystal ball” images show what the Gorge might well look like had the Scenic Area Act not been passed.

“The Columbia Gorge would be a very different place without the protections of the National Scenic Area,” Friends of the Columbia Gorge Executive Director Kevin Gorman said in an email to the organization’s followers. “Unchecked residential, commercial and industrial development would have consumed parts of it, transforming cliffs, forests, meadows and desertlands into crowded commercial and residential expanses stripped of scenic beauty and ecological integrity.”

Sandy River Delta: In Troutdale, Ore., this riverfront land was once zoned for industrial use. Today (left), the 1,500-acre natural area is used for horseback riding, hiking, biking, wading, fishing, bird-watching and other activities. Image: Friends of the Columbia Gorge

Titled “What if the National Scenic Area never existed?” the project was inspired by conversations within the organization about how to convey to the public the impact of the conservation work done over the years by Friends of the Columbia Gorge and other individuals, private organizations and government agencies.

“It’s simple to show what does exist—forests, streams, cliffs, wildlife, rural communities, etc.—but the true impact lies in what isn’t there,” Tim Dobyns, communications and engagement director for Friends of the Columbia Gorge, told Columbia Insight.

“The area we now know as Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge was being considered for a nuclear power plant,” said Gorman. “The large, undeveloped Steigerwald and Sandy River Delta lands were zoned for industrial use.”

Friends of the Columbia Gorge engaged an AI designer in Madison, Wisc., to create its somewhat dystopian views of what might have been.

Getting to a finished product required lots of trial and error.

“The process combined Photoshop’s generative fill feature for basic shapes—houses, roads, buildings, wind turbines, mines, etc.—with a program called Stable Diffusion to refine those elements into realistic visuals,” according to Dobyns. “This two-step approach helped us reach (a) level of detail and realism.”

Clear not crowded: The view today (left) from the Washington side of the Gorge at Beacon Rock might be quite different but for massive preservation efforts. Image: Friends of the Columbia Gorge

Without protections, the Gorge would likely be a lot “smaller,” at least in the public’s imagination.

“Today, we think of the Gorge as stretching 85 east-to-west miles from the Sandy River to the Deschutes River,” said Gorman. “Without the National Scenic Area, most people’s perception of what the Gorge is would be the 15-mile waterfall corridor between Latourell Falls and Eagle Creek.

“Without the land-use laws the National Scenic Area created, what would have become of the outlying areas? One only has to look at what lies at the base of the Smoky Mountains in Tennessee where the once-small communities of Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge have gone into tourism overdrive to capitalize on the draw of the nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park.”

The full project and all of its dramatic images can be viewed at the Friends of the Columbia Gorge website.

Cliff Bentz is a third generation Oregonian, raised on his family’s cattle ranches in Harney County. He is probably overjoyed to read and view Chuck Thompson’s piece on development in the Columbia Gorge.

It looks like a very nice power point development plan to me, and I’m sure it will to the hybrid Presbyterian/Catholic fellow soon to be in the White House.

A much better view of the future of the entire Inland Pacific Northwest, not just the Gorge gateway, is available from the Official Harney County website, and can be crossed checked for accuracy by taking a browser to Afghanistan, U.S. Department of State, including level 4, do not travel.

Please note, both sites use late winter and early spring images for their presentations.

Happy to see that this didn’t happen. By the story, is it going to? Just seems like something that the FED should keep their grubby little hands out of.

You seem a bit confused. It was the Federal government that protected it. That’s why it’s a National Scenic Area. The U.S. Forest Service manages much of it.

Keep the Columbia Gorge just like it is . In fact , the homes that are still in the boundaries that are protected should be destroyed after the owners pass on . Love the Gorge .

Without the Scenic Area, Troutdale n Washougal would have sprawled east into the Gorge. Thank you to Nancy Russell for leading efforts for protection.

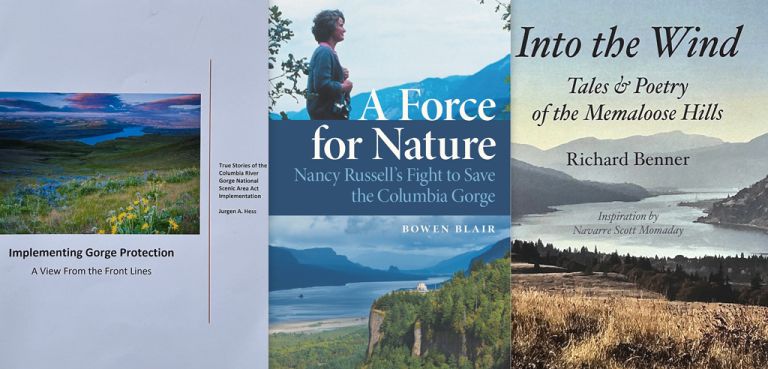

By Jurgen Hess, retired US Forest Scenic Area manager