Snake River chinook are now “quasi-extinct.” That’s scary news for more than just salmon

Dark times: Across the Columbia River Basin, the sun is setting on more than just the water. Photo: Luke Detwiler/CC

By Andrew Engelson. December 16, 2021. In mid-November, I ventured to a creek not far from my home to have a look at the spawning chum salmon. Amid the fallen leaves of Oregon maples and red alder, dozens of fish pushed against the current, mottled and battered after their long journey from the Pacific.

As I watched the fish using their last ounces of strength to fulfill their genetic destiny, I wondered how long this miracle life-cycle could endure.

And I pondered a term I’ve recently been coming across with increasing frequency: quasi-extinction.

The concept of quasi-extinction has been around for decades, used in studies of species decline ranging from monarch butterflies to emperor penguins.

But we’ve started hearing more about it around the Columbia River Basin thanks to a recent study.

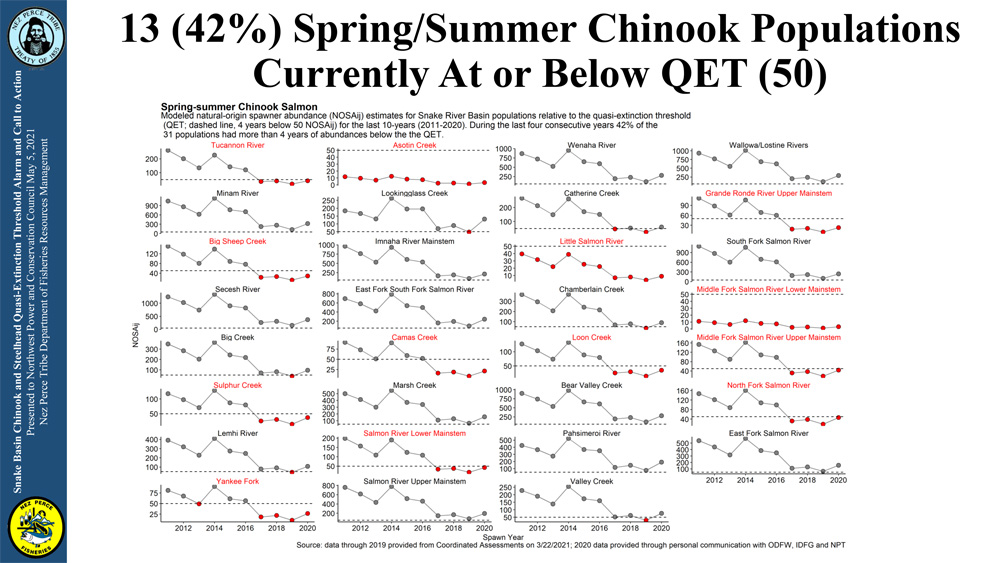

In April of this year, the Nez Perce Tribe announced that populations of spring/summer chinook salmon in the upper Snake River Basin are in steep decline. The message from the tribe was stark: 42% of wild chinook populations in streams that feed into the Snake are now in a state of quasi-extinction.

If the current rate of decline continues, by 2025 77% of those chinook populations will meet the quasi-extinction threshold.

It sounds dire. But “quasi-extinction” is a gauzy term. What does it really mean?

Working definition

According to Brad Hanson, a wildlife biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries whose area of expertise is the Southern Resident orca, the idea behind quasi-extinction “is that (a) population essentially is still in existence, but reproductively speaking, there’s no way in the world it can increase.”

More bluntly, as Nature.com put it, “A quasi-extinction threshold reflects the fact that a population may be doomed to extinction even if there are still individuals alive.”

Quasi-extinction arises when the density of reproductive individuals in a given population becomes so small that it’s unable to sustain a growing or even stable population.

For spring/summer chinook in the Snake River Basin, NOAA has its own specific definition of quasi-extinction, says Jay Hesse, director of fisheries biological services for the Nez Perce Tribe. If a particular stream has 50 or fewer natural-origin spawners for four years in a row, Hesse says, the population is considered in quasi-extinction.

Chart from April 2021 Nez Perce Tribe report “Snake River Basin Chinook and Steelhead—Quasi-Extinction Threshold and Call to Action”

Quasi-extinction is more useful for ecologists and wildlife managers than absolute extinction because it represents a more realistic indicator of when populations are reaching a point of no return.

“What we want is something that represents a dire condition,” says Hesse, “but not game over.”

A species can continue to exist for years after reaching a quasi-extinction threshold—or even decades for long-lived species such as orcas—but the path is set.

Explaining chinook quasi-extinction

Myriad obstacles stand between Columbia River Basin chinook and survival—most significantly, the presence of four dams on the lower Columbia River and four on the lower Snake River.

Reservoirs behind the dams slow the movement of water. This exposes juvenile salmon to predators for longer periods of time.

Nez Perce fisheries biologist Jay Hesse

Additionally, all that slow water combined with rising temperatures linked to climate change often proves fatal for chinook.

“The water temperatures have been impacted by the reservoir environment,” says Hesse. “They’re essentially heat traps.”

Add to that increased competition from non-native species such as smallmouth bass and walleye, and the deck is stacked against chinook.

The Nez Perce are doing what they can, supporting habitat restoration, hatchery operations and water management.

But what salmon really need is transformational change, says Hesse. All the modeling he’s seen points to one significant tactic: removing the four dams on the Lower Snake River.

“In all cases, the data supports that the highest rates of survival would result from taking those dams out,” says Hesse.

Orca effect

Orcas and chinook are intricately linked. According to NOAA’s Hanson, studies of fecal samples from Southern Resident orcas in and around the Salish Sea indicate as much as 90% of their prey is chinook.

Take a good look: Southern Resident orcas are endangered in part because they can’t find enough food. Photo: National Marine Fisheries Service

And when orcas venture out of the Salish Sea in search of food, more than half the time they’re heading to the mouth of the Columbia River.

“They’re chinook specialists,” says Hanson. “If they had their choice, they’d take chinook 24/7.”

Because runs of chinook in California and Oregon are in steep decline, the Columbia River is often the Southern Residents’ only feeding option.

“And if that system fails, where do the whales turn then?” Hanson wonders.

In addition to serving as prey for orcas, chinook are integral to the economy, culture and traditional heritage of the Nez Perce.

“It’s more than just the economic value to us,” says Anthony Capetill, a research biologist and tribal member. “It’s a cultural value and a life source that we heavily rely on—not just for our sustenance but for our identity.”

Quasi-understanding

Though the Southern Resident orcas haven’t reached quasi-extinction yet, their status is precarious.

Only 73 individuals remain, and though a significant breeding population exists, mortality of young orcas is a concern.

Hanson says biologists spotted three pregnant females in the Puget Sound J pod this summer, but they’ve still seen no evidence of new calves this fall.

Fewer and smaller chinook, combined with marine vehicle noise and pollutants, are all making recovery of the Southern Resident orcas difficult.

“Everything is chipping away at all they’ve evolved to do,” says Hanson.

This year’s declaration of quasi-extinction of Snake River chinook was a shock to many.

Let’s hope its meaning and wider implications are better understood in the critical years ahead.