Photo by Mark Giuliucci.

After being nearly eradicated from North America during the 19th century, beavers are now being recognized by ecologists for the crucial role that the rodents play in restoring and preserving biodiversity.

By Valerie Brown. Aug. 22, 2019. Neatniks treasure square corners, straight lines, the absence of clutter. A neatnik-approved landscape has tidy, free-flowing rivers with well-defined margins, nice flat meadows that can be turned into fields, and clear lakes free of debris.

That appears to have been the model used by the first Europeans settling on the Atlantic shore. Over the next four centuries, they applied the model continent-wide. From the colonial period to 1990, the United States lost more than half its wetlands, resulting in erosion-plagued rivers and creeks, depleted water tables, desertification, and the disappearance of mammals, amphibians, fish, reptiles, insects and plants.

Thus did neatnik ideology ravage a continent. Finally, now that the devastation is painfully obvious, people are returning to the original engineers of the primordial paradise: beaver. And with catastrophic climate change looming, the world’s second largest rodent is looking more and more like a potential knight in furry armor.

Complexity: The more life there is, the more life there is

Beaver have taught observers that what looks like chaos is really complexity, and complexity is just another word for biodiversity. Beaver turn simple creeks into complex wetlands. Their ponds retain surface and groundwater and keep it cool. The shallows shelter salamanders, tadpoles, young fish and insect larvae. Around beaver, riparian plants are more diverse. Floods are less catastrophic. Streamflow persists through the dry season. Turbidity declines. In other words, beaver are “the most important thing on the landscape from a biodiversity perspective,” says Michael Pollock, a fish biologist and beaver believer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Fisheries Science Center.

Ye Olde Near-Extinction

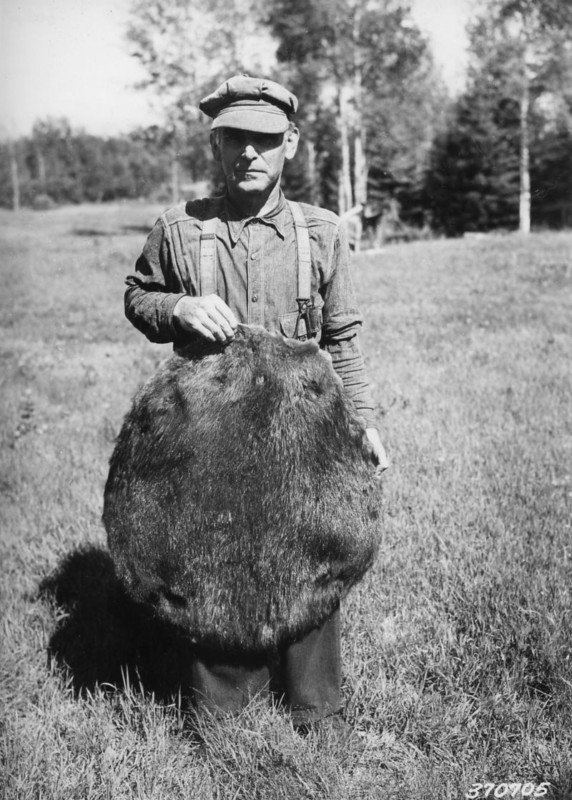

As Ben Goldfarb notes in his excellent book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beaver and Why They Matter, the pre-European beaver population of North America is estimated at 60-400 million. Because their fur made perfect top hats for toffs, beavers were hunted to near-extinction throughout the continent. Even though the carnage ceased around 1870, when silk became haute couture for top hats, by 1900 there were only about 100,000 beaver left. Estimates of the current North American population range from 12 to 15 million.

Prized by hat makers for their fur, millions of beaver were trapped and killed during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Attitudes eventually changed. Beaver enthusiasts admire Dorothy Richards, who adopted a remnant colony of beaver in New York’s Adirondack mountains in the 1930s. In 1948 the State of Idaho began to drop beaver from airplanes into wilderness sites in wooden crates. Some beaver actually survived. These days beaver relocators use humane cages and try to bring the entire family along if possible. They also build “beaver dam analogues” to provide a bit of infrastructure for further beaver development, and sometimes they build makeshift startup lodges so the beaver will have a place to hide from predators. These practices have increased the success rate of beaver relocations, and there are now numerous programs in the Northwest to relocate the animals rather than kill them. The Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group, for example, partnered with the Yakama Nation over five years to effect 45 beaver relocations in Yakima River tributaries, of which 16 resulted in new colonies that built 26 new dams, 24 ponds, and stored 24.6 million gallons of water.

Move over, salmon

Much conservation policy in the Northwest pivots around salmon. The federal government and the states have treaties with the Yakama, Umatilla, Nez Perce, Warm Springs and numerous other tribes to ensure sustainable salmon harvests. Public and private stakeholders have slowly come to realize that beaver help salmon, and recent research suggests that endangered coho salmon may not be able to recover at all without help from beaver.

Acknowledging beavers’ assistance represents quite a turnaround for many fish experts. Because some salmon advocates picture a large concrete barrier when they hear the word “dam,” they were slow to recognize that beaver dams are no obstacle to salmon, says Pollock. Beaver believers point out that if beaver dams were a barrier, the legendary salmon runs up the Columbia, Snake and Salmon rivers would never have existed. The punchline of a Native American story says it all: “Beaver taught salmon to jump.”

The Long Arm of the Law

State and federal statutes and policies reflect the historical status of beaver, usually defining them only in economic terms. For example, one Oregon statute defines beaver as “predatory animals” and “noxious rodents.” (Beaver are mostly vegetarian, and their usual victims are trees and shrubs, especially willows..) Another statute labels them “protected furbearers” on public land, where they can be killed for their pelts. Yet several Oregon agencies also sponsor and participate in beaver restoration programs. The same is true for Washington and Idaho.

Predatory? Maybe if you’re an alder branch. Photo courtesy of Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group.

Federal policies are likewise inconsistent. Between 2010 and 2016, The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s “Wildlife Services” program (known as APHIS) killed 772 beaver in some of the same coastal Oregon counties where NOAA says coho salmon desperately need beaver ponds. A threatened lawsuit in 2018 by the Center for Biological Diversity and other environmental advocates prompted suspension of the USDA program, but the conflict has not been resolved. (Neither the USDA nor ODFW responded to requests for comment.)

Urban beaver

Most stakeholders agree that beaver belong in the wilderness, even if they don’t want them on private land. But who wants a beaver colony inside city limits? At least two cities in the West have said “We do.” The small city of Martinez, California adopted a beaver colony that set up shop in the middle of town 20 years ago. In Eugene, Oregon, beaver have colonized the Delta Ponds, which are former gravel extraction sites near the Willamette River. The surrounding area is wetland, and city ecologist Lauri Holts credits the beaver with making habitat for many other animals, including green herons and pond turtles. The endangered Fender’s blue butterfly, king skimmer dragonflies, wildflowers, and river otters also call the area home.

If you are a city dweller, you may be living with beaver already. In Seattle, beaver expert Benjamin Dittbrenner found evidence of beaver in all the natural stream systems that he surveyed. The city has been fairly libertarian, Dittbrenner says, allowing its parks and greenspaces to “get beavery.” But he cautions that “if you build a park and don’t identify the areas where beaver may colonize, you’re going to be forever retrofitting or constantly relocating them. We want urban land planners to think ahead.”

What to do with a nuisance beaver

Margaret Neuman, executive director of the Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group, says, “I occasionally get a call from landowners saying, ‘I have the perfect stream, I’d love to have a beaver.’” That’s always good news for beaver advocates, but many landowners don’t want to tolerate beavers’ propensity to kill trees and flood fields.

Once considered a nuisance, this beaver finds a new home in the upper Yakima River. Photo courtesy of Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group.

“I get calls from landowners losing thousands of dollars worth of trees,” says Terry Brant, a licensed nuisance animal trapper in the Eugene area. Brant has seen no indication that local property owners view beaver as anything but pests. “Nobody has ever approached me to start relocating beaver,” he says. “A homeowner is not going to pay the kind of money it takes to do that.” (Beaver removal can cost upwards of $500 per job.)

A 2011 report from the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife found that property owners who had had already dealt with beaver on their property were the most likely to see them as a problem. There was a strong east-west attitude gradient, with farmers and ranchers east of the Cascades more likely to kill beaver than were property owners in the Coast Range or urban areas. A federal study of Idaho’s Owyhee County found that most ranchers leasing BLM land for grazing wanted beaver to return to the area but preferred them to stay upstream of their cattle operations.

Until all the available human-compatible beaver habitat is filled, there will be a chance to turn nuisance beaver into miracle workers. There are now professional beaver relocators available in most of the Pacific Northwest, many of whom also work closely with landowners who want to co-exist with beaver. The Spokane-based Lands Council has been very successful at relocating problem beaver in private forests and even some ranches and farms as well as on public lands. Executive director Mike Petersen says, “The first priority if the beaver builds a dam [on private land] is to talk with the landowner to see if there’s something we can mitigate.” Mitigation can include wrapping trees in metal mesh, installing pond levelers to keep the pond at a bearable size, and installing “beaver deceiver” fencing around culverts.

A climate for change?

Further shifts of hearts and minds regarding beaver may occur courtesy of climate change. Much of the Pacific Northwest is desert, and under climate change the arid lands are going to both expand and become even drier. Beavers’ ecological contributions could play a crucial role in ecosystem resilience. Installing beaver would be an economical and low-maintenance way to retain more water in the region’s watersheds compared to massive reservoir construction projects. But can beaver replace snowpack, which provides much of Northwesterners’ municipal and agricultural water?

“No,” says Dittbrenner, who modeled the approximate storage capacity of beaver-designed hydraulic systems. “The sheer magnitude of snow volume in the Cascades is not something beaver could make up for at any population level.” But in the interior deserts and rangelands, he added, “Beaver could potentially offset snowpack and increase summer storage by 20% of the existing volume.”

So the muddy waddlers are no silver bullet. There is no single way to recover from the neatnik catastrophe. But that doesn’t mean humans can’t learn a fundamental lesson from beaver: complexity is the key to ecosystem viability. Beaver activities benefit almost every other life form from butterflies to moose.

Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

And it’s not just practical benefit. As is often the case, many of North America’s indigenous peoples had the sense to appreciate what beaver were contributing to human well-being just by existing. (Although for a distinctly noir take, see “Beaver Gods Are Jerks – Wishpoosh, Antediluvian Terror of the Pacific Northwest”). Even a hard-core empiricist like Michael Pollock finds them “the sweetest nicest creatures.”

“I’ve never met a beaver that wasn’t friendly,” he says. “I’ve seen videos of mean beaver but I’ve never met one. They’re very intuitive.”

Valerie,

Excellent!

jerry mallett

Colorado Headwaters.org