By Nolan Morris. Nov. 12, 2015. The quality of a river is dependent upon its tributaries. The drought crisis on the Deschutes River this past summer marks a stark warning. In the coming years, similar issues may be felt throughout the Columbia River Basin.

[/media-credit] “Under rigid drawdown schedules many trout were left high and dry” when their water ran out.

The health of the Columbia River is dependent on the immense watershed that supplies its water and the life within. Ranging across seven states and one Canadian province, the headwaters of the Columbia are vast.

The current drought has brought into question the health and management of various rivers throughout this region. The Deschutes River, and more specifically, the portion referred to as the Upper Deschutes–ranging from the Wickiup Reservoir down to the city center of Bend–has been in the headlines a lot this summer as the ecological health of the river falters and the visibility of how the river is managed increases.

“Mild and anemic” is how Gail Snyder of Central Oregon Landwatch referred to the Upper Deschutes River, which is protected under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. More than a convenient play on words, this depiction of the river is heartbreakingly accurate for substantial portions of the river.

This October marked the third consecutive year that fish have had to be rescued from stranded pools of water along the Lava Island Falls channel of the Deschutes River. This year’s effort, led by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, saw over 3,500 trout rescued in addition to hundreds of sculpin and whitefish. Kim Brannock witnessed the drying up of this channel in autumn of 2013 and the dead fish that lined the rock bed of the channel. Compelled to do something, she gathered some family members, buckets and nets and rescued as many of the surviving stranded fish as possible.

After her third year involved in the rescue, Kim started the Deschutes River Keepers, which she hopes will fill a void in representing the ecological well being of the Upper Deschutes River. Brannock is quick to point out that the Lava Island fish rescue effort represents a small portion of the fish stranded throughout the entire river and that the stranded fish are only one of many devastating symptoms of a river whose health is wavering.

[/media-credit] Staff and volunteers work to catch and move fish to deeper water.

Traditionally known for its incredibly consistent year-round water level (the river benefits from a large system of natural springs), the Upper Deschutes River now suffers severe ecological degradation. This is due to drastic changes to the river level, as managed by Wickiup Reservoir. April through September marks the irrigation season throughout Central Oregon, which means Wickiup Reservoir releases water at a flow rate averaging 1300 ft3/s, but ranging as high as 1900 ft3/s.

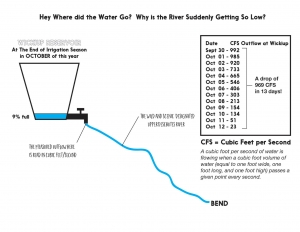

Come October, the reservoir begins to save water again for the following year, meaning water is discharged at a drastically reduced rate. On October 2, the discharge rate was at 920 ft3/s, and by October 12 the rate was down to 23 ft3/s (data retrieved from Bureau of Reclamation website, code WICO). This is a 4,000 percent reduction in the amount of water flowing in the Upper Deschutes River over the course of two weeks. An environmental science background is not required to recognize this artificial imbalance imposed upon the river will have extreme negative repercussions.

The abnormally high water flows during irrigation season are equivalent to a 25-year flood under natural, unmanaged river conditions. This results in massive logjams and destructive erosion, which uproots trees, destroys portions of the riverbank and deposits excessive sediment downstream (Bend’s Mirror Pond is the end destination for much of this sediment).

[/media-credit] The outflow of Wickiup is rapidly reducing. “It goes from a rushing full river, to a trickle at 23 cfs over a total of just 13 days.”

From flood-like conditions during irrigation season, severe drought-like water flows are then imposed (the 20 ft3/s water flow rate is four percent of the river’s natural flow rate) during the winter months when the river is managed to refill the reservoir. This incredibly unnatural change in water flow conditions has drastic environmental consequences. Large ecosystems, which developed and adapted to the high water level over the previous six months, are lost. Marshes, side channels and large portions of riverbed go dry. Fish, insects, macro invertebrates, amphibians and various species of birds all lose essential wild habitat used for spawning, foraging, hunting and shelter. The natural balance necessary to support a healthy ecological system is gone. For a powerful visual depiction of the physical and biological changes occurring throughout the Upper Deschutes, view Scott Nelson’s video, Rivi’re des Chutes II.

Understanding of the fragility of the river’s ecological make-up is not new. A 1947 study published by the Oregon State Game Commission (predecessor of Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife) foresaw the environmental dangers that lay ahead as plans for the Wickiup Reservoir went into action. Dimick et al. write, “Fluctuating stream levels are detrimental to fish life in several respects, and to reduce these effects to a minimum; still keeping in mind irrigation needs, it is recommended that the flow of the Deschutes River below Wickiup dam never be reduced to less than 200 ft3/s.

Furthermore, in reducing the flow to this level, the process should be gradual.” The authors predict fish stranded and killed in side pockets, interference with spawning activities, loss of waterfowl nesting habitat and other ecological damage. With flow levels far below the recommended minimum and not managed in a ‘gradual’ manner, the river has seen the environmental dangers become reality.

[/media-credit] Photo taken along Upper Deschutes River just downstream of Wickiup Reservoir (11/5/15)

Gail Snyder believes that change will result as the public becomes more knowledgeable of the environmental sufferings of the river this community loves so much. She expressed little faith in the river’s current management groups, saying that, “unless the public really demands change, I don’t see that we will actually have change.”

The Deschutes River is not alone in its problems, other rivers suffer throughout the drought-stricken west. But it’s well positioned for action. It’s surrounded by passionate stakeholders interested in the Deschutes as a source of natural beauty and escape, and is also a major revenue generator for the Central Oregon economy. A 2011 University of Michigan study estimates the river’s economic contributions to be over $185 million, with the largest sector being tourism, not agriculture.

Ecological systems are fragile; however, they are also resilient. Improved management and restructuring water-use incentives for this incredible, yet degraded, river will allow it to return closer to its wild and scenic self.

Good article. Clearly the issue in question here is the maintenance of century old water laws that only see a river as a large irrigation canal and which mandate water waste – the Use It or Lose It doctrine. This framing of the value of a river no longer works in the 21st century and what is needed is a hard re-boot that mandates efficient end use of water and takes into full account river and ecosystem health.

The drought that covered the west this summer is projected to be with us for years to come. It is clear from the drastic measures in California and only slightly less stringent water restrictions in Oregon and Washington that water use and water rights will have to be revisited.