State report attempts to acknowledge a biodiversity crisis and that too many people are trying to access the same resources

Fair share: Stakeholders are grappling with ways to ensure equal access to public resources. Photo: WDFW

By K.C. Mehaffey. October 12, 2023. To environmental groups, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission’s draft conservation policy is a long overdue recognition that the state’s fish and wildlife belong to everyone, and that there are urgent new threats to preserving them.

But to hunters, it’s a clear attempt to strip them of traditional values and hunting culture they believe is under attack by a commission that no longer holds a majority of fishing and hunting advocates.

And to the nine-member commission, the draft policy reveals a serious trust issue with a key demographic and long-term partner in the state’s effort to preserve fish, wildlife and their habitats.

Native American Tribes in the state are also upset that they weren’t consulted as sovereign nations and management partners.

The policy outlines the commission’s increasingly difficult job of conserving fish and wildlife due to climate change, a growing human population and development. Its purpose is to direct the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife to proactively address these current and emerging conservation challenges.

The seven principles include a recognition that conservation is a top priority; that conserving all species, habitats and ecosystems is important; that strong partnerships are needed; that decisions should be based on objective, science-based knowledge; that uncertainty should be taken into account when making decisions; that innovative solutions will be needed; and that expanded partnerships, authorities and funding are necessary.

Those same principles are expanded on in much more detail in the WDFW’s 25-Year Strategic Plan, which was well received when it was adopted in 2020, Commission Chair Barbara Baker told Columbia Insight.

Three years later, the proposed conservation policy has become highly controversial. Out of over 1,660 comments sent by email or given in public testimony, three out of four were opposed to it, Nate Pamplin, WDFW’s director of external affairs, told the commission in August.

While conservation groups appreciate the policy for acknowledging the intrinsic value of natural resources and the growing challenges in preserving them, hunters and hunting groups question the need for it, contending that it’s not aligned with the commission’s mandates and departs from tenants of the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

WDFW Commission Chair Barbara Baker. Photo: WDFW

“I was really surprised at the blowback we received when the document went out for public review in April,” said Baker, who’s been working with other commissioners on the policy since 2021, and was excited about the simplicity of the 15th draft.

She said the three-page document was an attempt to acknowledge that the state is facing a biodiversity crisis, and that too many people are trying to access the same resources.

Since the pandemic, all uses of Washington Fish and Wildlife lands—not just hunting and fishing—have gone up 20%.

The reaction is confusing, Baker said, because the commission didn’t have a similar pushback to the strategic plan, and because they’ve been hearing from all groups—including hunters—that the state needs to conserve its natural resources and carefully manage them so they will endure into the future.

“So that’s what we tried to do,” she said.

Baker added that the policy was never intended to displace traditional stakeholders. It was meant to be additive, and to memorialize what had already been adopted in their strategic plan.

“The way I see it, we have groups of current Washington citizens that are all angling for a voice,” she said. “That is, the general population represented by many interest groups, and they’re passionate because they think we’re out of time. We have the hunters and anglers, and right now, the hunters especially think their way of life and their traditional values are in peril. And the tribes, who are just really angry we didn’t bring them in sooner.”

Groundbreaking shift or radical departure?

At their June 22 meeting, commissioners listened to public testimony about the proposed policy.

Alex Baier, regional director for the Washington chapter of the pro-hunting Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, called the policy “a radical departure from traditional conservation.” He said that the new policy entirely redefines conservation.

“What is conspicuously missing from the newly invented definition which was prominent in previous iterations, are words like management, to start. Restoration, science-based, sustainable use, ecological, and even the compromising ‘or’ have all been extirpated,” he said.

Baier noted that the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation has contributed more than $133 million to conserve or enhance over 500,000 acres in Washington alone. And many other hunting and fishing groups have provided similar financial support.

Claire Davis, president and interim executive director of Washington Wildlife First (which says it’s “dedicated exclusively to monitoring and reforming” the WDFW), applauded the commission for recognizing that conservation should be its first priority.

Claire Davis. Photo: Washington Wildlife First

“Conservation should be placed first for the end goal of conservation, not—as an earlier speaker said—for the purpose of long-term sustainable consumption,” she said.

Davis urged the commission to adopt the policy “without watering down its terms, although we’d be happy to see you strengthen it even more.”

She said she’d like to see the commission move away from the idea that wild animals are property, and would also like it to retire the use of the word “harvest” when talking about wild animals.

The policy, she said, recognizes that wildlife and nature have intrinsic value. To her, she said, that means “We realize that fish and wildlife have their own place in the world—a right to exist in their own right—and not just for the sake of being used by people.”

Several Washington residents who did not represent an organization testified, too.

Sam Bruegger, of Brewster, told commissioners that she has a small child who loves wild animals, from orcas to insects and everything in between.

“Every decision you make here affects him, and it will affect him in the future,” she said.

Bruegger said that she doesn’t see the policy as excluding hunting groups, but rather as an inclusion of all.

“When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality can feel like oppression,” she added.

Justin Boardman told the commission that sportsmen today deal with a lot of division across the country that includes anti-hunting activism. He accused WDFW of being “heavily influenced by emotional decisions versus science-based facts.”

He asked the commission to educate itself and base its decisions on facts rather than emotions driven by anti-hunting organizations.

Several hunters focused on the policy’s use of the word, “preservation” rather than “conservation,” which to them indicated a movement away from consumptive uses of fish and wildlife.

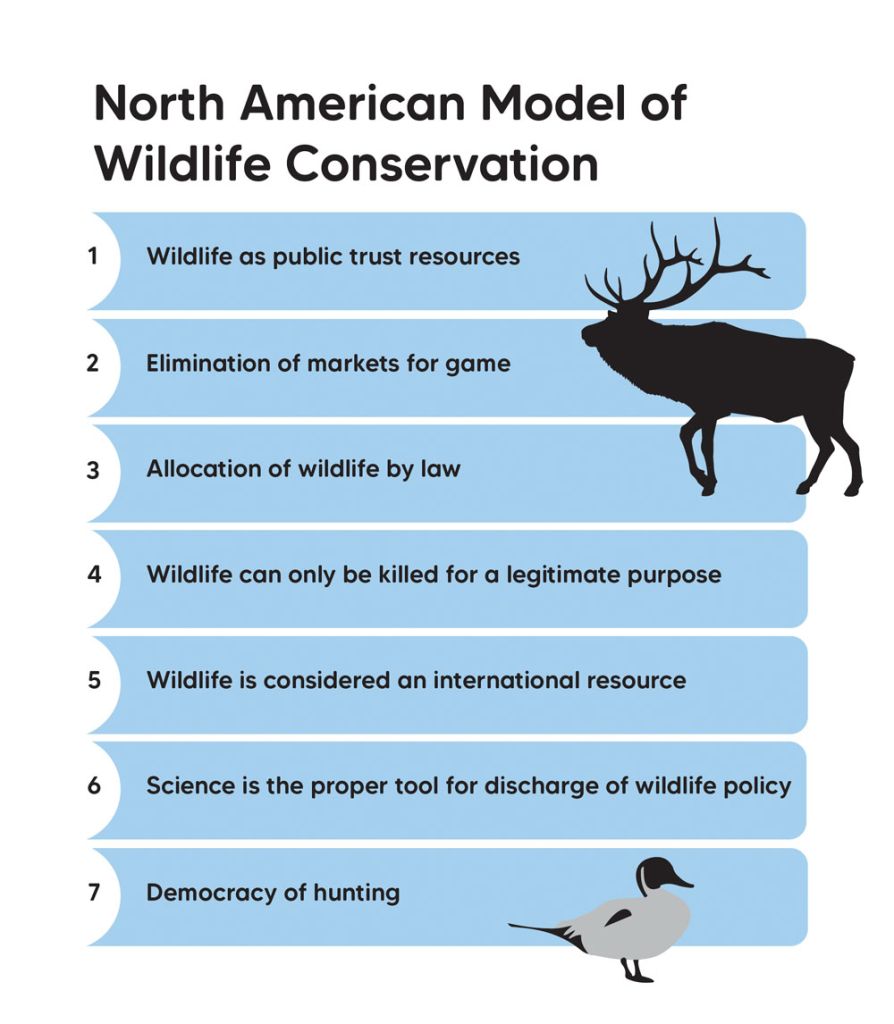

Many criticized it for being a departure from the North American Model of Conservation.

North American Model of Conservation

With so many hunters commenting that the draft policy is a departure from the North American Model of Conservation, commissioners scheduled a presentation on the model during the Aug. 11 meeting.

They flew in one of the model’s co-authors—John Organ—a wildlife biologist who serves on the Fisheries and Wildlife Board for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (Although the North American Model of Conservation has its roots in 19th-century conservation movements, it wasn’t formally articulated until 2001.)

Organ told commissioners that the narrative that has surrounded the idea of the North American Model of Conservation has become distorted, and he felt compelled to set the record straight.

He noted that the role of hunters in conservation is indisputable. But there are many others who have been instrumental in pushing for and getting conservation measures accepted and institutionalized.

“There’s a lot of credit to go around in conservation and the development of these principles,” he said.

Graphic: Mackenzie Miller

The North American Model of Conservation is a system of policies and laws to restore and safeguard fish and wildlife and their habitats through sound science and active management.

The model’s concept involves the public ownership of wildlife, as opposed to the landowner—or the king—owning it, as is the case in many other parts of the world.

The model focuses on the need to manage fish and wildlife for sustainable use.

“The model is what it is,” said Organ. “It’s not carved in stone. It has no legal standing on its own. But I would challenge anyone to contest any one of those principles.”

Organ said the model is a compilation of principles and policies that distinguish wildlife conservation in North America with conservation in other parts of the world.

But given the real and emerging ecological crises throughout the world, he said there’s a greater need now to focus on what may be preventing fish and wildlife managers achieving conservation.

“What we require, I firmly believe, is to commit ourselves to disallowing our discussions of the model to be constrained by a narrow bandwidth of thinking that enables us to talk only about tinkering here and tinkering there with a particular principle or a specific aspect of the model,” he told commissioners. “That is not enough for the conservation crises we are facing in this country, and in Canada, and around the world with respect to wildlife diversity, the integrity and connectedness of natural systems, and to the ecological fabric of this planet.”

Hunters “should be nervous”

At the commission’s Big Tent Committee meeting on Aug. 10, commissioners grappled with how a policy on conservation—something everyone appears to support—went so sideways.

Commissioner Lorna Smith said she thinks the commission failed to explain to the public that the policy was the next step in implementing the 25-Year Strategic Plan.

“It really is a next step, and I don’t think we made that clear enough,” she said.

Commissioner Steve Parker said it’s clear to him from the degree of polarization in the comments that the policy will continue to be a source of conflict and controversy.

“I keep looking for and trying to think of some way that we can eliminate these loaded terms—and I don’t pretend to understand how they became loaded terms but it’s obvious that they are—and find some language and definitions that are sort of agreeable to everybody,” said Parker.

Parker said adopting the policy now, with this amount of opposition from the hunting community, would send a bad message.

“I can’t believe that we, as a group and with the constituency that we have, that we can’t find a way for everybody to agree on what conservation is, and whether it’s a good thing or a bad thing,” he said.

Admitting he was being facetious, he suggested, “I think a decent policy statement is, ‘Conservation—we’re for it,’ and leave it at that, and let the parties decide for themselves what they think we mean by that.”

Call to arms: This land is your land. But who owns the wildlife? Photo: WDFW

But Commissioner Melanie Rowland said she thinks there are very different priorities and values and philosophies between the environmental groups and the hunters, and those differences will never be reconciled.

She said to her, the conservation policy is an intentional document to signal that the commission is looking at conservation with a broader goal than conserving fish and wildlife for hunting and fishing—which is what the department was initially created for.

She said there’s room for hunting and fishing, but added, “I understand the hunters and fishers could be getting nervous, and I think they should be getting nervous because they have been pretty much in complete control for a very long time.”

Commissioner John Lehmkuhl said the conservation policy isn’t a huge change from what WDFW is already doing. He said it’s something that should unify the public, not divide it. [A previous version of this story misspelled Commissioner Lehmkuhl’s name. The error has been fixed. —Editor]

“If conservation isn’t a unifying principle for everybody—all of our public—then we ought to just quit right now.”

Despite the polarized comments, Pamplin—WDFW’s external affairs director—told commissioners that the controversy could be resolved through the lengthy process of coalition building.

He noted the commission has faced controversial topics in the past that resulted in 9-0 votes and garnered general support by the public.

“The wolf plan is one of those examples,” he said.

Another is the Washington Wildlife and Recreation Program, which has had $125 million appropriated for land acquisitions with both Republican and Democratic support.

“We’re capable of doing big things, and we can do it in a way that’s not divisive,” he added.

To Baker, that involves admitting past mistakes, doing more work with tribes and stakeholders, and forging ahead.

Now what?

In August, commissioners still hoped to incorporate changes based on the comments they heard, and be ready to adopt a revised conservation policy at their Oct. 26-28 meeting.

That timeline is now uncertain.

After realizing their failure to formally engage with tribes, the commission’s Big Tent Committee reached out to several tribes and to the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, promising to consider their thoughts on the document—not only those covered under tribal treaty rights, but any other concerns they may have.

Baker noted that—based on the comments they’ve heard—opponents don’t object to the wording or language as much as they’re worried about the intent.

“So it’s a trust issue,” she said.

She’s not sure what the commission has done to earn this level of distrust.

“I don’t believe we are an anti-hunting commission,” she said.

Perfect site: The Yakima River is beautiful. It also has some of the best stream trout fishing in Washington. Photo: BLM

The perception could come from the fact that hunters and anglers are now sharing the stage with more people and groups worried about how fish and wildlife will survive the pressures of climate change and development.

“I think what’s happening here is that a lot of people in our state are starting to wake up and see that management of natural resources is something that’s important to them. Fish and wildlife, for many years, has been sort of the province of fishers and hunters. Nobody else was particularly worried about it because this is a state that strongly supports responsible fishing and hunting,” she said.

Baker believes one of the problems with the draft conservation policy is it doesn’t acknowledge the conservation efforts by hunters and anglers. So instead of people commenting with constructive ideas about how to implement a new conservation policy, commissioners heard a lot of anger over not being acknowledged.

It’s frustrating, Baker said, because the seven principles of the policy didn’t receive the attention they deserve.

“Some of us were hoping we would hear productive ideas about how to implement true conservation in the future. And instead, what we have heard is an awful lot of upsettedness or anger about not being acknowledged, and the insistence that the voice of whoever was speaking needed to be heard and heard the loudest,” she said. “It was a mistake. We should have put all that in there, and we could have avoided that controversy.”

She said regaining the trust of the hunting public and tribes is her focus right now.

Where the policy goes from here will be discussed in the commission’s Big Tent Committee on Oct. 26 and presented to the full commission for consideration.

One thing worth mentioning is that some comments opposing this are coming from out of state. These numbers and data should be made public, if the Commission and others think the numbers of comments pro and con are decisive in some way.

Also, the word “preserve” is actually in the legislative mandate, so the drama around that word is kind of unjustified.

Thanks for a great article.

You got Commissioner Lehmkuhl’s name wrong. Not Lemke.

Dear Commissioner Lehmkuhl: I apologize for the error and have corrected the spelling of your name and noted the change above. Thank you for reading Columbia Insight, and I hope the oversight won’t discourage you from becoming a regular reader. Chuck Thompson, Editor

I don’t understand why hunters are so defensive about proposals from non-hunters (not “anti-hunters”) and even hunters like myself to improve the status quo in wildlife management. The first tenet of the North American Model is that wildlife is a public trust. That means the state has a duty to manage and, yes, preserve ALL wildlife, for ALL of us, not just hunters, anglers and trappers. Doesn’t mean that there won’t always be hunting, fishing and trapping, it just means that protecting wild species and ecosystems should be the first priority of any wildlife agency. And everyone deserves to have a voice in how that gets done.

I don’t think hunters and fisherman are concerned about everyone having a stake in the game. I think many are rightfully concerned about the lack of clearly defined words that mean different things to different people.

Wildlife for all has been making a concerted effort in several states that would make it easier to install anti-hunting proponents on the governing bodies meant to manage game species. “Wildlife for All, an environmental nonprofit… organized by current and former employees of the Humane Society, the Sierra Club, Wildearth Guardians, Animal & Earth Advocates, and Project Coyote (among others)… describes the current system of wildlife management as “outdated.”

I can see how you may feel you are making wildlife management more inclusive. Something that is important (more stakeholders leads to better long term management) but your comments come off a bit disingenuous considering the composition of WFA.

I can guarantee you the Commission is in general anti-hunting.