The governor’s committee is ready to report on the future of the new industry with unprecedented energy-sucking capacity

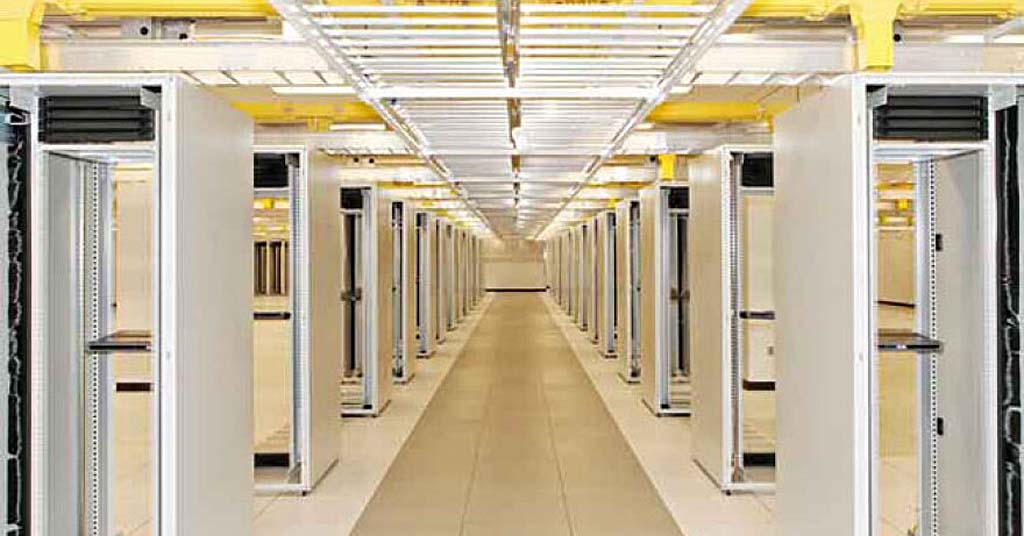

Profit center: The Sabey Data Center in Quincy, Wash. is a 530,000-square-foot, multi-tenant data center campus. Enviros are weighing the costs of such business. Photo: Sabey Data Centers

By K.C. Mehaffey. November 18, 2025. A forthcoming report from a task force formed by Wash. Gov. Bob Ferguson is certain to raise eyebrows in the environmental community.

With demand for new data centers to feed artificial intelligence surging through the Pacific Northwest, Ferguson convened the Data Center Workgroup earlier this year. He assigned the group to outline a future for the industry in the state.

The Data Center Workgroup met for six months and completed its job this month, adopting eight of nine policy recommendations. The group will submit its report to the governor on Dec. 1.

The workgroup’s eight adopted recommendations start by asserting that the state should “ensure Washington’s Climate Commitment Act and Clean Energy Transformation Act operate as envisioned to cover any fossil or unspecified power sources used by large data centers.”

However, according to workgroup member Zachariah Baker, regional and state policy director for the NW Energy Coalition, none of the eight recommendations require data centers to use clean energy when they’re built, or soon after.

The NW Energy Coalition is an alliance of about 100 environmental, civic and human service organizations, utilities, local government agencies, and businesses in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia.

Data centers require large amounts of constant power. Under Washington law, electric utilities are basically required to provide that energy.

In addition to power, some data centers, depending on their design, use substantial amounts of water for cooling, which can affect water levels and temperatures when it’s released back into rivers and streams. These actions negatively impact salmon, steelhead and other fish populations.

With AI on a fast track, the public is increasingly concerned about the impact large data centers have on the environment and government’s ability to meet mandated clean energy goals.

A Nov. 14 Wired story titled “The Data Center Resistance Has Arrived” reported that “local opposition to data centers skyrocketed in the second quarter of this year.”

Baker told Columbia Insight the workgroup recommendations are “a decent start, but incomplete.” He said the recommendations don’t go far enough to ensure a clean energy future or protect ratepayers.

“You can’t go a day without another article on data centers or AI,” said Baker. “It feels like a real moment here. We need to step up and figure out how to address it.”

Industry growth, tax revenue

The Data Center Workgroup includes representatives from electric utilities, data centers, environmental organizations, state agencies and the Yakama Nation.

But during a Nov. 13 Columbia Riverkeeper webinar titled “Unpacking the Impacts of Data Centers,” the organization’s policy director, Kelly Campbell, said the workgroup is “stacked with industry.” Columbia Riverkeeper asked to serve on the workgroup but was not selected.

With a directive to “consider policies that balance industry growth, tax revenue needs, energy constraints and sustainability,” the group discussed the impacts data centers are having on Washington’s economy, tax revenue, energy use and environment.

Cool job: Data center push AI, but some require lots of water to keep from overheating. Photo: Sabey Data Centers

In interviews with Columbia Insight, workgroup members advocating for the data center industry, clean energy and environmental justice said that although they couldn’t agree on several issues related to tax incentives, they’re largely satisfied with the process and final recommendations.

On topics where workgroup members disagreed, minority reports will be included in the report to lawmakers and the governor to provide a detailed picture of outstanding issues.

“This was an important conversation to have. We’re glad that the governor’s office put it together,” Cameron Steinback, climate justice program manager for Seattle-based Front and Centered, told Columbia Insight.

Dan Diorio, vice president of state policy for the national Data Center Coalition, told Columbia Insight he found discussions to be open, honest and fair.

The Data Center Coalition is a trade association that advocates for the data center industry. Its members include Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon Web Services and dozens of other major tech companies.

Although the Washington Legislature has a short session this year, workgroup members expect state lawmakers will continue data center conversations and propose new legislation in 2026. Some proposed changes could happen through rulemaking by state agencies.

Data centers imperil move to clean energy

The workgroup found that Washington is behind on building the generation, transmission and battery storage needed to achieve its clean energy goals. State policies require a carbon-neutral electric supply by 2030, and 100% renewable energy by 2045.

Even without massive new loads driven by the voracious consumption of data centers, the state’s energy needs are growing.

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council expects data centers and chip fabrication could add between 2,200 and 4,800 average megawatts of load by 2030.

Smart start: Google began building and operating its own data centers in 2006, starting with its location in The Dalles, Ore. Photo: Jurgen Hess

According to the Oregon Citizens Utility Board, a single data center can consume the same amount of power as a medium-sized city, such as Eugene, Ore.

One workgroup recommendation is to require large power users to cover costs of new generation, transmission or distribution systems.

Baker calls the recommendation “absolutely critical to the data center conversation and addressing the impacts.”

“It’s really important that they use clean energy now because if they don’t, it’ll be much harder to reach our climate and clean energy goals,” he said.

Sarah Wochele of the Oregon Citizens Utility Board is among many critics who believe data centers threaten the Pacific Northwest’s transition to renewable energy.

“Data center load growth is making meeting emissions requirements more difficult,” she said at the Nov. 13 Columbia Riverkeeper webinar.

In short, data centers are consuming more energy than is possible for renewable energy sources to keep up with.

If data centers build new natural gas-powered plants, the transition to carbon-free energy sources becomes that much more unlikely.

The tech industry is also pushing nuclear energy alternatives in the form of small modular nuclear reactors, or SMNR, as well as “unspecified fossil fuel consumption,” according to Lauren Goldberg, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper.

Steinback said the legislature will have to decide whether Washington’s priorities are to provide data centers a “cozy space to land,” or make sure that the state is sticking to its climate goals.

He said energy costs are already rising, and without clear regulations higher electricity costs and diminished air and water quality could harm local communities and low-income residents.

The data center industry supports the recommendations, but wants to be involved in the development of new rate classes or tariffs, said Diorio.

“It’s important to emphasize that the data center industry is fully committed to paying full costs,” he said.

Whoops: Learning from the past

The national debate over data centers raises the concern that AI may be a bubble economy that’s destined to pop.

As tech companies race to become the first to develop “superintelligence,” there’s a potential to overbuild data centers and related infrastructure that could become “stranded assets.”

That’s a term Washingtonians understand—if they’ve studied their own energy industry history.

In a nutshell, the Washington Public Power Supply System, colloquially known as “Whoops,” developed big plans in the late 1950s to build nuclear power plants.

“There needs to be a conversation about how much of this technology folks even want.”

“Planners expected that the demand for electricity in the Northwest would double every 10 years, beyond the capacity of hydropower,” according to History Link.

Instead, after one nuclear power plant was completed over-budget and behind schedule, the rest were mothballed then scrapped, leaving WPPSS utilities and their ratepayers holding the bag.

The $2.25 billion municipal bond default became one of the largest in U.S. history.

“It feels like there are some parallels there,” said Baker of the NW Energy Coalition, which got started during the Whoops era. “It’s not the same, but we can learn from those lessons.”

To that end, the workgroup’s recommendation on strengthening ratepayer protections includes a provision to require new large loads to cover all costs and avoid shifting those costs or risks onto other customer classes.

“Everybody’s still trying to figure out AI and data centers,” Baker said. “I think there needs to be a conversation about how much of this technology folks even want.”

“What are they hiding?”

Columbia Riverkeeper studied the impacts of data centers and published a brief in September.

It examines data center-driven needs for energy and water, and the impacts that unchecked data center growth could have on the state’s clean energy goals.

“We’re kind of getting these shoved down our throats by big tech,” said Riverkeeper’s Campbell. “I question the urgency that the data center industry is pushing.”

Fall in line? It remains to be seen how the governor and legislature will respond to the Data Center Workgroup’s recommendations. Photo: Washington Consolidated Technology Services

Her organization would like to see a moratorium on new data centers until various issues are resolved—something not recommended by the workgroup.

“We do not have the correct regulations set up to handle these huge-load data centers,” and until they’re in place, the construction of new, large-load data centers should be paused, said Campbell.

Asked at the Nov. 13 webinar if the enormous amounts of water required for cooling data center equipment is potable after being used, she replied: “The answer is we don’t know. And part of that is that these data centers do not want to give out information about water usage. … A lot of these questions we should be able to answer. But when they’re not sharing this information, you know, what are they hiding?”

Big tax breaks for data centers

The workgroup found that tax incentives saved data centers and their tenants about $584 million from 2012 through 2023. Over $118 million of that came in 2023.

But those tax incentives aren’t equal across the state and aren’t available in six of the state’s 39 counties.

The draft recommendation for tax incentives was the only recommendation of nine that wasn’t adopted. It would have expanded tax exemptions to all counties.

Baker said clean energy advocates want data centers to bring their own clean energy capacity as part of getting a tax break.

“Before we talk about expanding the tax incentives, we need to make sure we have all these protections in place,” he said.

But to Diorio, expanding tax incentives is a key to keeping Washington competitive in data center development. He said Washington is one of 37 states that have sales tax exemptions for data centers.

It’s not just about new data centers, he said. On average, data centers need to be replaced every three to five years, and continuing the exemption allows them to continue to invest in the state.

From the industry’s perspective, Diorio said data centers—which do pay state and local property taxes—have brought significant economic benefits to some of the Washington communities where they’re located.

The city of Quincy, for example, has been able to replace, upgrade or build important infrastructure over the last 20 years, including a new reuse water system and wastewater treatment plant, new sidewalks, new schools, a new hospital, a new city hall and a new fire station.

A report by the accounting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers—commissioned by the Data Center Coalition—found that in 2023, data centers in Washington contributed $1.8 billion to state and local taxes, and supported 8,990 direct jobs.

Diorio said that a study by Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission found that 83% of data centers in that state used the same amount of water or less than an average large office building.

Transparency, sustainability

Diorio said he’s concerned about the possibility of the state requiring a sustainability report, since water and power use by data centers are constantly changing as companies replace their infrastructure on a rolling basis.

Steinback said the recommendation for data centers to publish annual sustainability reports is key.

“I want to highlight the importance of transparency,” he said. “These are very large-load entities. They need to track and regularly report publicly how much water they’re using, how much electricity they’re using and how long or how frequently they’re running generators.”

He said his organization, Front and Centered, will be engaging in discussions with the governor and legislature.

“The question is out there: How much do we accommodate these really, really wealthy businesses?” said Steinback.

Data centers consume a lot of power, but it’s not too much for renewable energy to keep up with.

China is installing 1,000 MW of solar per day, and 1,000 MW of wind and 1,000 MW of batteries per week. Data center growth is much slower than that. If we made a commitment, we could achieve the goal of clean energy for data centers.

About half of the energy for data centers is for the computer load. About half is for the cooling load. With large storage tanks for chilled water, like the Google Data Center at The Dalles has, the cooling load can be served entirely with variable renewables, making chilled water when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing.

These data centers are a serious threat to the existence of Columbia River salmon and Pacific lamprey stocks. The dams’ turbine created energy that these centers require is already pressuring reduction of spill over dams, critical for safe passage of juvenile salmon and lamprey and also adult salmon that need passage safe passage over dams. The significant consumption of water to run these centers is also a major environmental cost. Are these mega tech companies required to have water allocation permits from the state?