The viability of prized species depends on the health of smaller species. Yet we continue to ignore the obvious

All together now: Freshwater mussels, like these in Oregon’s John Day River, are becoming increasingly scarce. The implications are wide-ranging. Photo: Leanne Tippett Mosby

K.C. Mehaffey. June 6, 2024. All of the habitat work in the Columbia Basin designed to help restore salmon and steelhead is benefiting other aquatic life, too—right?

Alexa Maine says not always. As lead biologist for the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation’s freshwater mussel research and restoration project, Maine says all too often, salmon habitat restoration projects overlook one of the river’s most important creatures—freshwater mussels.

She says a habitat project is planned, and then as an afterthought someone realizes that a bed of mussels is located right where the heavy equipment will be digging out a channel, or in an area that will be dewatered.

Sometimes, they dig up the mussel bed and move them to a safer location.

Despite these good intentions, Maine says in many cases, 90% of the mussels will die—whether they’re moved one inch or one mile.

“They are reliant on a place. They have been there for a minimum of 10 years, if not 80 or 90 years,” she tells Columbia Insight.

People working to save the smaller and largely unnoticed aquatic animals of the Columbia Basin say the salmon-centric focus of restoration is missing the bigger picture.

“For us to have healthy fish populations, we really need to have healthy mussel populations,” says Emilie Blevins, senior conservation biologist with the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation’s endangered species program.

Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity, agrees, and adds snails to the list.

“Without saving the mussels and snails, we won’t be saving the salmon,” he says.

This is because some of the Columbia Basin’s smallest creatures—like mussels and snails—aren’t only indicators of the river’s health, they’re also critical to the health of the entire ecosystem.

Threatened, endangered

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering petitions to list the western ridged mussel and two snail species—the shortface lanx and the ashy pebblesnail—as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

The petitions note that many of the same reasons salmon and steelhead have experienced sharp declines throughout the Columbia River Basin are also true for these mussels and snails.

Freshwater mussels and snails require cold, flowing waters; they’re sensitive to rising stream temperatures. Unlike salmon, they can’t escape changes to their habitat.

“They are not meant to move, so they can’t get away from high temperatures and low flows,” says Maine.

Search party: Alexa Maine counts mussels while snorkeling in the John Day River. Photo: Leanne Tippett Mosby

The impacts of dams and the creation of reservoirs, along with habitat destruction and pollution from agriculture, urbanization, logging, livestock grazing and streamside development have all contributed to a vast shrinking of these species.

The climate crisis and altered ecosystem caused by invasive species are magnifying those impacts.

Once widespread throughout the Columbia River Basin, shortface lanx and ashy pebblesnails are no longer found in many tributaries, including the Clark Fork, Spokane, Kootenai, Willamette, Malheur and others, the petition to list them states.

The western ridged mussel once thrived in five western U.S. states and British Columbia. Scientists believe the southern extent of its range—once in San Diego County, Calif., has largely moved 475 miles to rivers north of San Francisco Bay, and that many remaining populations have diminished in number, and may not be reproducing.

The western ridged mussel was once widely distributed throughout Washington, Oregon and Idaho, and the Columbia River continues to be a stronghold.

However, three of the four rivers where the mussels have experienced rapid die-offs—when thousands suddenly perish—are located in the Columbia River Basin.

Western ridged mussels are a long-lived species. In a healthy environment they’ll live for between 40 and 80 years, according to Maine. But that means it can take 15 to 45 years for a colony to replace itself.

Amazing life of mussels

Maine can hardly contain her enthusiasm when she talks about the life cycle of a western ridged mussel.

She heads up the only freshwater mussel propagation lab in the West and hopes to one day to figure out the secrets of producing them artificially to be released back into parts of the Columbia River Basin where they once thrived.

They need a boost, she says, because processes that normally happen in the wild are becoming less viable.

Muscle memory: A western ridged mussel in a tributary of the Chehalis River in 2017. Mussel populations in the Chehalis basin are in a severe state of decline. Photo: Xerces Society

Maine explains what it takes for mussels to reproduce: To become pregnant, a female mussel siphons water day and night, eventually taking in sperm from a male mussel that could be located a mile upstream. Only then she can produce larvae.

“Mussels are so badass, they use their gills for respiration—breathing—and to pass food particles, but also to hold their larvae,” says Maine.

Like little marsupials, mussels hold larvae in the water tubes of their gill chambers, reducing their own ability to eat and breathe.

When its larvae are ready to be released, the mussel creates a package containing thousands of larvae. This package just happens to look like an aquatic insect that a host fish—preferably a sculpin—wants to eat. The mussel releases this package at dawn or dusk, when sculpin are most likely to be feeding.

The sculpin, an opportunistic feeder, is fooled into gobbling down this package of larvae. But when it turns out not to be a delicious worm, it flushes the whole thing out through its gills. The pressure breaks the larvae out of its egg casing. In the process, a fraction of larvae attach themselves to the sculpin’s gills. There they remain for about two weeks, until they’re large enough to live on their own.

Maine says lab studies have shown it doesn’t hurt the sculpin to host the tiny mussels—the size of a half-grain of sand—in its gills for a couple of weeks.

She believes sculpin are a limiting factor in the survival of western ridged mussels in a warming climate.

“Sculpin are extremely thermally intolerant, so even though the mussel itself might be able to handle warming waters, the host fish may not,” she says.

Sculpin, she adds, are another under-studied and under-appreciated species in the Columbia River Basin.

Riverkeepers

The need to protect these three species is just a fragment of the greater need to recognize and protect the interconnected nature of all species throughout the Columbia River Basin, says Greenwald.

He notes that 74% of freshwater snails and 72% of freshwater mussels in the United States and Canada are imperiled.

“We just have to do everything we can to protect rivers, from their headwaters to the mouth,” he says. “It really takes a whole watershed approach.”

To Greenwald, the rapid loss of mussels and snails—which he calls building blocks of aquatic life—is as concerning as climate change.

“They’re really interrelated, and we need to get a handle on both of these things if we want to have a livable future,” he says.

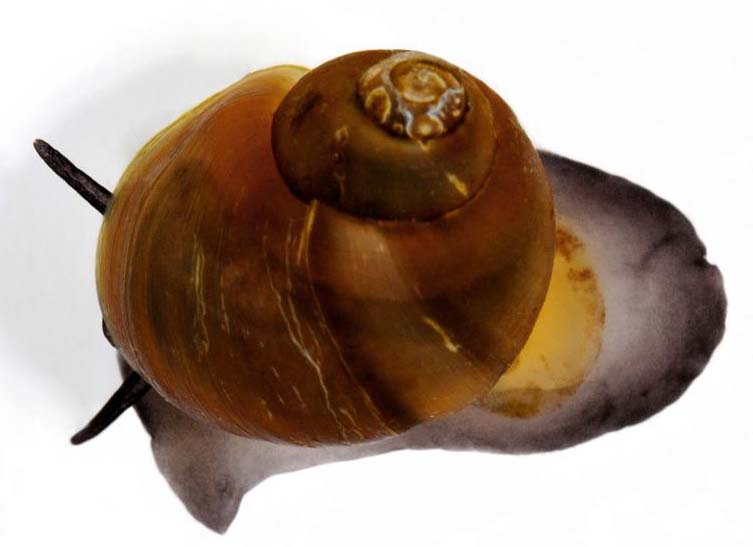

Ashy pebblesnail. Photo: WDFW

In the watershed ecosystem, snails are an important food source for salmon and other fish. They also help keep rivers and streams clean.

Mussels are such masters of filtering water they’re sometimes called the liver of the river.

They improve water quality by removing particles from the water, filtering out bacteria, phytoplankton, zooplankton, fungal spores and algae. They also remove unnatural substances from their environment, such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, herbicides, flame retardants and E. coli, storing them in their tissues.

A mussel can filter 10 to 15 gallons of water a day.

“In high densities, collectively they can filter a substantial quantity of water; increasing water clarity for salmonids and other fishes,” according to the petition to list them.

Blevins says studies are finding other reasons mussels are important to the ecosystem. Research has found that lamprey larvae grow faster at a site with mussels, and fish in isolated pools are more likely to survive when mussels are present.

She notes that the western ridged mussel is the only member of its genus on earth.

“They’re a very distinct species that has a really close relationship with sculpin and other native fish that people don’t appreciate,” she says. “They’re a good representative of why it’s important to care about the little things.”

Historic importance

To Maine, there’s yet another reason to work on rebuilding western ridged mussel populations: they’re a First Food for Tribes throughout the Columbia River Basin, a staple part of Indigenous Peoples’ diet for many generations.

While Tribes have retained the right to gather them, “mussels cannot sustain a harvest, so that organism has been lost from the dinner table because there are so few,” according to Maine.

Fewer mussels also mean that individual mussels carry a much higher load of toxins, she says.

Good flex: Western pearlshell mussel. Photo: Leanne Tippett Mosby

But losing the mussel is not just about food.

Mussel shells were traded and used for adornment and jewelry. Because it’s been generations since they were harvested, Tribes are losing the knowledge of the places where they were collected, how they were gathered and prepared and their value to people and the environment.

“It’s holistic, community-based restoration,” says Maine. “Instead of restoring a reach for salmon, we restore the whole watershed for the provision of First Foods, and for many generations in the future.”

She remains hopeful that one day freshwater mussels will again be plentiful enough, and healthy enough, to resume their place at the dinner table.

As part of that effort, she’s working to figure out how to propagate mussels in a 1,000-square-foot facility in Walla Walla, Wash.

“We produced 5,000 western ridged mussels last year. … We have tens left,” she says. The project uses sculpin as host fish but researchers haven’t figured out what juvenile mussels eat.

It took decades to perfect Pacific lamprey propagation and now Tribes are producing and releasing 1 million a year. It may take 10 or 20 more years, but Maine is confident.

“We will get there,” she says.

Mysterious die-offs

To Maine, the sudden die-off of a mussel population in the Middle Fork John Day River “was one of the most devastating things I’ve ever experienced.”

The stretch of river was once considered the “mussel mecca” of the West, she says, with a dense population of 500 mussels per square meter when it was surveyed in 2003 and 2004.

“By 2007 to 2008, it was zero,” she says. “It was one of the first documented mass die-offs in the U.S.”

From 2008 to 2022, no mussels were found in this quarter-mile section of the river.

Finally, in 2022, surveys discovered couple of mussels—not western ridged mussels, but another native species called western pearlshell.

“The population is now at about 22 mussels in that location where there used to be thousands. They are rebuilding, but it’s not the same species,” she says.

Valuable find: Emilie Blevins of the Xerces Society teaches volunteers about freshwater mussel traits and habitats. Photo: McKenzie River Trust

Emilie Blevins of the Xerces Society had a similar experience in the Chehalis River in southwest Washington. There, tens of thousands of dead freshwater mussels—including western ridged mussels—were discovered where live ones were observed two years earlier.

Other observed die-offs have occurred in the Crooked and Grande Ronde rivers, and potential die-offs—which had not been previously surveyed—may have occurred in the John Day, Weiser and Owyhee rivers.

There could easily be more.

“Because freshwater mussels are cryptic, and because western ridged mussel populations are not routinely monitored or studied across the species’ range in the U.S., die-offs may go unnoticed,” reads the petition to list them as threatened or endangered.

Blevins says since 2018, biologists have been more frequently and thoroughly monitoring mortality events, and are discovering that these events spreading, and hitting otherwise healthy mussel sites.

“When we don’t know what’s killing them in the only habitat they’re still in—that’s where it gets really scary,” she says.

Blevins believes a virus or disease of some kind is at the heart of the die-offs.

“We see it move upriver, so it doesn’t seem like it’s runoff from something, or a spill or chemical, because it has the potential to be transported upstream,” she says.

What also disturbs Maine is that even in healthy populations, “We very rarely see younger mussels. I can count on one hand the number of very young—young-of-the-year—individuals I’ve seen in almost 15 years of sampling.”

Blevins says the massive die-offs brought immediacy to the need to list western ridged mussels as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

“The fact that over the course of a month, an otherwise completely healthy mussel bed could be struck down—that added impetus,” she says.

Long road to ESA listing

In 2020, the Xerces Society filed its petition to list the western ridged mussel as endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

In 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed that a listing may be warranted. A decision is expected in January 2025.

Blevins says when a species is listed, studies and consultations must ensure that federal actions don’t further jeopardize the species.

“When there are federal activities, they would have to take into account the potential effects on the species,” she says.

Agencies can also enter into landowner agreements or issue permits to ensure species are protected through restoration efforts.

“As things stand now, western ridged mussels don’t have any other meaningful protection in Washington or Oregon,” she says.

In April, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a petition asking the agency to consider an endangered or threatened listing for shortface lanx and ashy pebblesnails.

Greenwald says it takes years to get the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to make a determination on a petition to list.

“We know we’re going to have to file lawsuits to get dates” for a decision, he says.

The slow process will play out during a time when species need more protections than ever.

“We’re in an extinction crisis around the world,” says Greenwald. “All of our food and most of our medicines come from species. The fact that we’re losing these building blocks should be of concern.”

Greenwald notes that listing the snails or mussels would prompt new considerations of how dams are managed to make sure they’re not causing harm, or that the harm is mitigated and reduced. Similar considerations would be given to activities like livestock grazing and logging.

Maine, Blevins and Greenwald each say more awareness of the issue is sorely needed.

Blevins recently attended a presentation showing a river’s ecological web, depicting complex relationships from aquatic insects all the way up to fish and mammals. But it didn’t even include mussels.

“There’s still such a huge gap in appreciating the value they have,” she says. “They’re doing all these incredible things, and most people don’t even know they exist.”