Anglers love them but the invasive species could undo years of salmon recovery efforts in the Columbia River Basin

Space invader: Walleyes are unwelcome in the Snake River. They’re multiplying anyway. Photo: Idaho Department of Fish and Game

By Kendra Chamberlain. April 10, 2024. Fish managers across Idaho, Washington, Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and the Nez Perce Tribe have joined forces with NOAA fisheries and the U.S. Geologic Survey to hold off the invasion of nonnative walleye fish before they do any more damage to vulnerable salmon and steelhead populations in the Snake River.

Walleye, the beloved game fish of the Midwest, has been present in the Columbia River system since the 1940s and reached Snake River in the late 1990s.

By then, researchers had realized the species was actually contributing to salmon and steelhead population declines.

Now, the fish are moving into upstream anadromous rearing habitat.

“That’s when it starts getting really concerning,” Marika Dobos, anadromous staff biologist at the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG), tells Columbia Insight.

Dobos and other fish managers are worried the species could undo the precious progress made on rebuilding salmon and steelhead populations in the Snake River, particularly fall chinook.

In March, Dobos gave a presentation to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council on the walleye invasion and the working group that has convened to stop it.

“Fall chinook nearly blinked into extinction in the Snake River. And a lot of folks have worked really hard to build that program up over the years, and have done a really good job,” Dobos told the council. It’s one of our few success stories in the Clearwater. If the walleye are able to establish in upstream habitats, it could undo a lot of that work in a short amount of time.”

Adept adapters

Walleye are an extremely effective invasive species: they’re good at adapting to different types of environments; they reproduce relatively quickly; and they eat nearly anything they cross paths with.

In fact, it’s not unusual for walleye to eat themselves out of a habitat by decimating populations of native fish.

The walleye’s native prey have spent millenia developing spiny fins to fend off the toothy predators.

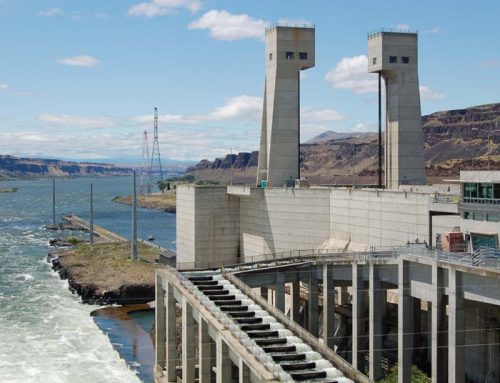

But in the Columbia and Snake River systems, the native fish are soft-finned, and thanks to the extensive network of dams throughout the basin, often get caught up in slow-flowing reservoirs and dam bottlenecks as they make their migrations.

It’s a buffet for the walleye.

The fish loiter around the tail races of the dams, eating as much as they can.

Walleye populations have exploded as a result, Dobos says.

There are more predators eating more fish each day.

Fishing favorite

Idaho Department of Fish and Game staff know the walleye have made it past the Lower Granite Dam in eastern Washington.

Dobos says she’s not sure if the walleye have figured out how to pass the dam on their own and are now reproducing upstream, or if they’re being illegally introduced by anglers.

That’s another dangerous trait of the walleye: they’re popular with anglers.

The species’ explosive expansion across the lower 48 has been due in part to fish managers introducing the species into new areas to provide recreational opportunities.

Walleyes are still being stocked in some areas of Washington and Idaho.

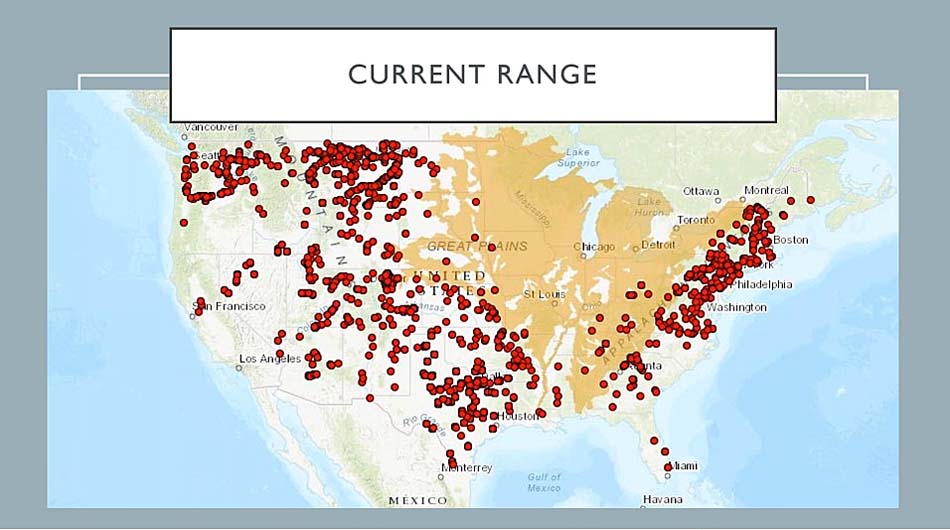

Walleye native range indicated in orange. Chart: Marika Dobos/IDFG

Walleye expanded range indicated by red dots. Chart: Marika Dobos/IDFG

The fish also have a vocal cohort of supporters among the angling community in Idaho.

Anglers illegally introduce the species to new water bodies. Dobos says it’s become common practice for walleye enthusiasts to release any big females that they catch—despite the state asking anglers to keep all walleye they find.

Eradicating the species from the Snake River seems unlikely at this point. But the working group hopes to be able to at least stymie the fish’s progress into the rearing habitats upstream of the dams.

The group had its first meeting in January.

“[That meeting] was just trying to have some discussions about some of the concerns that we had and the values and better coordinating amongst these key agency folks,” Dobos says. But coordinating across so many groups will be a challenge. The first step is to make sure everyone is on the same page.

“This is three different states, there are sovereign nations involved and federal agencies. We think there’s value in making sure that our message is consistent. It’s pretty complex. It’s gonna take a lot of time.”

Put a bounty on them and teenage boys will catch them for the money. Use the fish to feed people and as fertilizer.

Me and a couple of friends that are retired are going down twice a week even in the winter time right now on the snake River just below lower Granite dam we average catching about 13 to 17 walleye a day. They average between 18 to 24 inches long. We have caught a few in the 10 pound range. I think the state of Washington is starting a little late about curbing the effect of walleye on salmon and steelhead. They will need to put a bow on them if they want more and more fisherman to pull them from the river. I would fish them every day if there were a bounty on them. I think fisherman could put a pretty good dent in them on the snake river