About 12,000 acres near the town’s water supply will be logged in the name of safety. Critics say that’s just an excuse to cut down trees

Logging on: Walla Walla, Wash., resident Paul Lynn has questions about a planned timber cut in the Mill Creek Watershed that supplies water to the town. Photo: Eli Francovich

By Eli Francovich. December 11, 2025. East of Walla Walla, Wash., a gate protects 36 square miles of steep country; country that funnels rain and snowmelt into Mill Creek, which in turn serves as the primary water supply for nearly 34,000 people. Closed to the public since 1918 the land is patrolled and trespassers face stiff fines and jail time.

Yet there may be a threat to the watershed that doesn’t respect gates, imprisonment, fines or any other human legislation: wildfire.

If a crown-scorching, soil-eviscerating fire—the kind that has become more common as the West heats up—ripped through these slopes it could flood Mill Creek with ash, clog it with burned trees and saturate the water with mud. This would devastate a town that doesn’t filter its drinking water, relying instead on the watershed’s purity and some UV and chlorine treatment.

At least that’s what the U.S. Forest Service and town managers say. And the best possible fix according to them? A timber sale.

“When we’re in July or August and a thunderstorm roles in, I don’t sleep well,” says Ki Bealey, director of Walla Walla’s Department of Public Works. “It’s worrisome. It’s very worrisome.”

And so the U.S. Forest Service, with the support of city administrators and the Walla Walla fire chief, is moving forward with a “thinning” project.

The Tiger-Mill Project timber sale is slated to thin or log nearly 12,000 acres of forest, much of it within the Mill Creek watershed; a watershed that is a designated roadless area and hasn’t been logged for 100 years or more.

The rational, Bealey says, is to reduce lighter and flashier fuels so the catastrophic fire of his serotinal nightmares can’t occur. Or, as the Forest Service states on its website, the project will “protect the Mill Creek Municipal Watershed and restore ecosystem processes and functions that foster landscape diversity and achieve desired vegetation conditions.”

All of which is little more than greenwashed commercial logging, says Paul Lynn, a Walla Walla resident who has vociferously fought the project.

“Commercial thinning is kind of a euphemism for heavy logging,” Lynn says while driving alongside Mill Creek on brilliant October day.

In the past seven months Lynn has organized resistance to the project. The project is moving forward and an environmental assessment finding no significant impact was issued in Feb. 2025. process included a public comment period.

Lynn says the Forest Service and the town of Walla Walla did not adequately inform the public of the project and that the environmental review was inadequate.

And while he has numerous detailed critiques and concerns—ranging from faulty survey techniques to worries about potential flooding downstream following the logging—he questions the larger argument that logging helps forests. Instead, it’s just a rebrand, he says.

“Meet the new logging, same as the old logging. This country was built on timber, and I have no illusions about ending logging and I have certainly bought my fair share of sawn logs,” Lynn says in a 45-minute video laying out his concerns with the Tiger-Mill timber sale. But let’s call an axe an axe, if we’re dead set on cutting down trees lets at least not pretend that its good for the forest.”

Feeding the beast

Even before the Forest Service started using wildfire prevention as a reason to sell more timber, as reported earlier this year by Columbia Insight, the idea that selective logging, or thinning, could improve forest health was an established theory, one that makes intuitive sense.

The idea goes like this: Starting in the early 1900s the Forest Service put out every wildfire it could, as quickly as it could. This policy developed in response to a series of mammoth 1910 fires that burned 3 million acres and annihilated towns throughout the Northern Rockies. However, like any overcorrection there were unintended consequences.

Walla Walla County in red. Map: Wikipedia

“By trying to stop all major wildfires, the Forest Service had only fed the beast. The woods were full of dry, dying, aging timber and underbrush—fuel. Big swaths were unhealthy, in need of a cleansing burn. Even with their armies, their aerial support, their billions in taxpayer money to hold back the flames, rangers became increasingly helpless,” wrote author Timothy Egan in his book The Big Burn, which chronicles the 1910 fires and birth of the modern Forest Service.

In the following decades, commercial logging in the United States decreased due to increased costs, industry consolidation, globalization and social and political pressure. Previously logged forests, which often were replaced with stands of homogenous trees, grew thick with underbrush and immature trees, neither logged nor burned.

While hotter and drier summers certainly contributed to this, ecologists and managers began blaming forest management practices, namely suppression.

The best ways to counter this? Fuels reduction an umbrella term that encompasses thinning (the removal of small trees), controlled burning and the removal of larger trees, more closely resembling classic logging.

This has become accepted practice with support from many ecologists, scientists and managers.

However, there remain dissenters, voices that question the motivations, methods and science of fuel reduction.

“Thinning doesn’t stop fires,” says Chad Hanson, the co-founder the John Muir Project and a vocal critic of thinning. “It doesn’t prevent fires and it doesn’t prevent high-intensity fires.”

Against the grain

The Tiger-Mill Project is a perfect example of how the Forest Service uses the fear of wildfire as a cudgel to push timber sales through the court of public opinion, says Hanson.

In reality, projects like this harm forest health, do nothing to reduce fire severity and give homeowners a false sense of security, he says.

“The Tiger-Mill Project will put communities at greater risk,” he says. “While at the same time wasting an enormous amount of money.”

Cut and dried: Paint and paper guide loggers to trees included in the Tiger-Mill Project. Photo: Eli Francovich

Hanson is a prominent critic of forest thinning practices. He’s written op-eds in the New York Times and co-authored numerous research papers critiquing thinning.

In 2021 he wrote the book Smokescreen: Debunking Wildfire Myths to Save Our Forests and Our Climate.

He’s been characterized as one of the few dissenting voices, as evident in a 2023 High Country News article defending thinning. And his methods have been critiqued.

A 2019 article in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment attacked Hanson’s methods and motivations, accusing him of selectively using data and “pressuring scientists and graduate students with different research findings to retract their papers.”

Other studies, including a 2021 review of research, support thinning practices, sharply contradicting Hanson’s argument.

Hanson refutes these claims by citing a slurry of studies, many of them conducted by Forest Service ecologists and scientists.

“It’s really important to keep in mind that most of the research I’m relying on is not my own. In fact, a lot of it has been published by Forest Service scientists,” he says. “Thinning, as a so-called fire-management approach, is profoundly controversial even within the Forest Service.”

Thin argument

Hanson argues that the severity of any given wildfire depends primarily on the weather and environmental conditions.

Wet forests don’t burn easily. Dry ones do.

The removal of trees and underbrush allows more sunlight to hit the forest floor, drying the soil and the fuels that remain. At the same time, the reduction in trees allows winds to blow with less restriction, further fueling the flames.

The 2018 California Camp Fire is an example. The forest had been heavily ‘thinned’ and yet that fire killed 85 people and burned more than 150,000 acres.

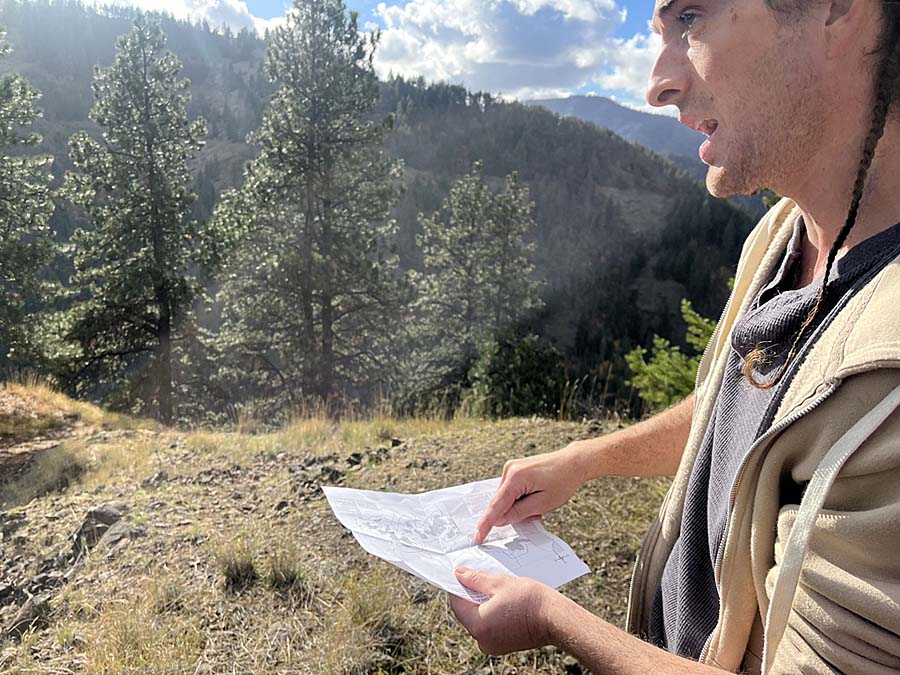

Deep cut: Paul Lynn examines a map showing areas that will be thinned as part of the Tiger-Mill Project. The Walla Walla resident organized opposition to the plan. Photo: Eli Francovich

A 2023 research paper co-authored by the Forest Service points to the importance of creating defensible space around homes in wildfire terrain and other ‘home-hardening’ techniques and finds that thinning far from homes has no impact. Similar studies, including a 2000 Forest Service study, reinforce this claim.

“(Thinning) gives communities a dangerous false sense of security,” he says.

Not to mention what commercial thinning entails.

While the word itself may invoke images of chaps-wearing hand crews walking through the woods selectively felling sickly trees, the reality is mechanized.

According to Hanson’s research a normal “so-called thinning project” kills between 70 and 80% of the trees in a given stand. Between 60 and 80% of all grand firs and Douglas fir between 10 and 20 inches could be removed according to the Tiger-Mill silverculture report.

“The term thinning has become a political term. Not a scientific term. It’s a wildly misleading term,” says Hanson.

Risk management

Proponents of the Tiger-Mill sale acknowledge that the project isn’t a perfect solution. But as they see it, it’s better than doing nothing.

And there’s at least one example where a wildfire torched a Colorado town’s drinking supply, forcing the purchase of a costly filtration system.

On Nov. 5, the Walla Walla City Council voted 4-3 to not send a letter to the Forest Service requesting a monitoring plan and a pause on work until that requested plan was approved.

“This is risk management, that’s really what it is,” says Bealey, the town planner, adding that even the Tiger-Mill Project doesn’t guarantee the town’s water supply won’t be destroyed by a fire.

“Is there a perfect option here?” he asks. “We’re doing our best to be prepared for the risks and manage the risks to the best of our ability.”

And while the outcome isn’t what Lynn fought for, the public interest is a win.

“The real outcome of this to me, regardless of the city council decision, is that local leadership is keenly aware of the fact the public is paying close attention to this project,” says Lynn. “And that we will be holding them accountable.”

Dr Jerry Franklin says Chad Hansen cherry picks his data in his studies to make his points. In his review of Hansons book, Franklin told me Hanson would rather let forests burn up. As a retired USForest Service person I respect Franklin’s viewpoint. I study and report on wildfires

After erroneously stopping all fires for 90 years fuels have built up that when a fire comes it will be a high intensity fire and burn up everything.

I would like to know examples of the cherry picking you refer to? Chad provides ample evidence in his book that forests burned historically at mix severity (including high severity), and that we should embrace fire for forest health (to reclaim an agency line). He would “rather let forests burn up” is an interesting statement. By “burn up,” do you mean they no longer have timber value and therefore no value at all? If so, the wildlife, vegetation communities, and soils would like a word with you… And nobody is “letting” these large, wind driven fires burn. They just burn. It’s this illusion of control that blinds us and fuels certain thinking like “if we only do more thinning, mowing, and mastication” we can stop or prevent the next mega fire. I tremble thinking about what we are currently doing to our forest ecosystems in the name of wildfire safety. Future generations will be bewildered this went on for so long. We are bloodletting the forests. It’s not working for communities and ecosystem, and the land management agencies keep doubling down. All to get out the cut.

That sort of vague, completely unsupported personal attack has become common from scientists who are funded by the US Forest Service or other logging interests. If they could make a substantive argument to explain away the many dozens of scientific studies that contradict the logging-as-fire-management narrative, they would do it. The fact that they don’t do this, and instead resort to baseless personal attacks, tells you everything you need to know about their scientific credibility, or lack thereof. Chad Hanson, PhD

The USFS is stating that thinning – commercial thinning that kills and removed mature trees — is the solution for wildfire. Where’s their data? Let’s take a look at what they’re talking about, where they’re talking about. With every example we will see thinning toast fails more than thinning that succeeds.

Dr Franklin — and anyone who’s out there promoting large scale thinning — needs to take us all out and show us what he means.

The public will see that there only a few small examples where forest treatments along with prescribed burning, resulted in a lower intensity of wildfire. The results are almost always worse more intense wildfires exactly where thinning has happened.

The author of this article is right: if someone wants to do commercial logging, just call it that. Stop glorifying it and calling it something it’s not.

There are no high severity fires anyplace in the West in my experience that occur without four major ingredients–drought, high temps, low humidity and most importantly high winds. Indeed, 90% of all fire acreage burned is attributed to wind.

The probability of these conditions occurring on any particular spot is exceptionally low. Why is this important? Because the thinning of forests ultimately has a limited effectiveness (assuming it is effective at all) because vegetation regrows. Often the regrowth is more flammable consisiting of grasses, shrubs and small trees. Furthermore, opening up the forest by thinning allows greater wind penetration and drying of soils.

The city of Corvallis, Oregon has been logging its city-owned forested watershed that supplies its highest quality drinking water for many decades. As water treatment costs soar, the city continues to argue that logging is needed to protect “forest health” even as residents have continuously tried to end the logging in favor of preserving older forests, biodiversity and clean water (https://friendsofthewatershed.org/).

There are many other factors in addition to the “catastrophic wildfire” idea. First, the forest service determined in their inaccurate and incomplete environmental assessment that an environmental impact statement was not needed. Logging in the Walla Walla watershed (an inventoried roadless area) will increase stream temperature and turbidity, reducing the value of Mill Creek for endangered species of fish and for the public water supply. Furthermore, logging in the watershed will make Mill Creek flashier, resulting in higher peak flows with more flood damage, as well as reducing the irrigation benefits of the Walla Walla River, especially in late summer. The only study of fire frequency in the Blue Mountains got samples for radiocarbon dating at an elevation of 3750 feet; the mean interval between major fires during the last 3500 years was about 660 years, with the most recent large fire occurring in 1855 AD.

Many of us local to this ‘project’ fear that all the costly non-commercial thinning and prescribed burning that helps sell it, will never happen. But the logging will. And yes, the first two actions out the door are two timber sales.