After deciding the U.S. government was never going to live up to its obligations, a pro-active plan to buy back its lands has brought the Umatilla Tribes national recognition

Forward view: Traditional Umatilla lands are gradually reverting to tribal control to benefit future generations, such as these girls in beaded regalia. Photo by Walters Photographers

By Wil Phinney. May 27, 2021. Thirty-two years ago, when the Umatilla Tribes realized non-Indians owned more property on the 172,000-acre reservation than the combined total for tribal government and tribal allottees, it embarked on a 50-year plan to buy back its land.

Thanks to an aggressive Land Acquisition Program, today the Tribes own 94,590 acres. Since 1990, the Tribes have purchased 77,346 acres—43,393 acres in fee status and 33,953 acres in trust status.

“After the 1855 Treaty, the Tribe’s homeland was reduced considerably,” says Bill Tovey, director of the Confederated Tribes’ Department of Economic and Community Development. “The Tribe figured the federal government would not live up to or solve the problems they created, so we developed our plan to buy back our homeland.”

About 24,000 acres of the 70,000 the Tribes have purchased are within the Tribes’ ceded territory but lie outside the reservation. That includes Rainwater, an 11,000-acre wildlife reserve near Dayton, Washington. It’s filled with mountain timber and is home to big game like deer and elk.

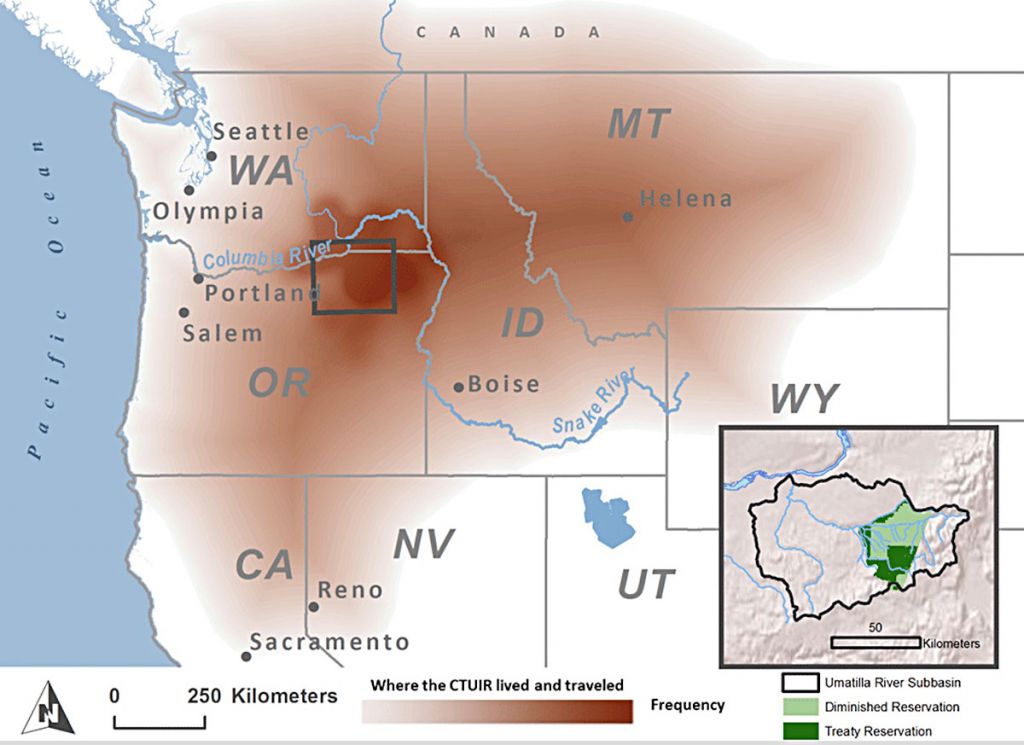

TRADITIONAL USE BY THE CAYUSE, UMATILLA, WALLA WALLA TRIBES

The Wanaket Wildlife Area preserve, about 2,700 acres some 60 miles north of the reservation near the Columbia River, is open for waterfowl hunting. The Wanaket property also includes 190 acres near the Port of Umatilla zoned for industrial use.

Another seven off-reservation parcels range in size from 45 acres to 666 acres. On-reservation, the 5,000-acre Wheelhouse property purchased last year, which the Tribes hope will become a popular area for hunting and gathering, includes steep, rocky ravines with some livestock grazing at the south end of the reservation.

The Tribes have also purchased several parcels on all four corners of Exit 216 on Interstate 84 for economic development.

MORE: Under pressure: The Oregon community desperate for water

“We figured out that if we wanted sovereignty, we have to have ownership,” says Tovey. “We had some regulatory authority, but better than regulatory is ownership.”

It’s a great story, but it’s one that started long before the 2020s or even before 1989 when the Tribes’ Land Acquisition Program started.

Creating the ‘checkerboard’

In 1855, the Umatilla, Cayuse, and Walla Walla Indians—the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR)—ceded some 6.4-million acres to the United States government with the promise of a 520,000-acre homeland in eastern Oregon.

Ground gamer: Bill Tovey, director of the Confederated Tribes’ Department of Economic and Community Development. Photo by Umatilla Tribes

A subsequent government survey reduced the reservation by almost half to 265,000 acres.

The Slater Act of 1885, specific to Oregon, and the General Allotment Act of 1887, reduced the reservation again to 172,000 acres.

In addition to making the reservation smaller, these two acts also led to the land, which had previously been used communally, being split up into individual allotments.

The U.S. government gave CTUIR males 160 acres, women 80 acres and children 40 acres. The rest was considered “excess” and sold to the white immigrants coming west, creating a checkerboard of Indian and non-Indian ownership across the reservation.

MORE: Opinion: Why the Gorge pumped-hydro project is opposed by the Yakama Nation

Indian-owned land has been divided into two types: fee and trust.

Tribal trust lands are held in trust by the United States government for the use of a tribe. The United States holds the legal title, and the tribe holds the beneficial interest. This is the largest category of Indian land. Tribal trust land is held communally by the tribe and is managed by the tribal government.

Fee land is reservation land no longer in trust or subject to restriction. Sometimes a tribe, or individual tribal members, has land in fee. The term refers to the “fee patent” document issued to the individual Indian landowner.

The allotment system further diminished the amount of Indian-owned land when allottees sold their parcels, which were often too small to earn a living from and too large to maintain.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“I’d put them in the top five tribes in the country for regaining lands.” — Cris Stainbrook, Indian Land Tenure Foundation[/perfectpullquote]

In 1920, Poker Jim, a headman for the Walla Walla Tribe, in a statement published in the East Oregonian newspaper, explained why the Walla Wallas were sending a delegate—his son—to Washington, D.C., to speak with Cato Sells, the commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1913-1921, about the allotment deal.

“We do not want these allotments and do not want patents [government grant] here,” proclaimed Poker Jim. “The game and fish is pretty nearly all gone from this country now and if you let the Indians get patents and sell off their lands pretty soon there will be no more home for the Indians here.”

Poker Jim’s statement appealed to Sells to help educate young men who, as soon as they got their allotment, would “sell their land and then they do not have any land and do not have any money because the money is soon spent and drawn, and the Indians are left without any home or any land to live on. Pretty soon, if you let them go on this way, the old Indians will be dead, and the young Indians will be beggars, because they will waste their land and money if they get patents.”

Despite Poker Jim’s request, non-Indians were allowed to purchase lands across the reservation.

Umatilla innovation

A strategy meeting in 1989 included representatives from the CTUIR, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and land experts like Cris Stainbrook, who is now president of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation headquartered in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Dave Tovey (Bill Tovey’s brother), a CTUIR planner at the time, wrote a 50-year plan that envisioned the Tribes directly owning or managing 40% of the reservation land by the year 2040. That’s a little over 100,000 acres of the land within the original 265,000-acre treaty boundaries—about six times more acreage than the CTUIR owned in 1990.

More out there: Blue Mountains above the Walawála Valley (Buckaroo Creek) on the Umatilla Reservation. Photo by Walters Photographers

Stainbrook was working at the time with First Nations Development Institute, a nonprofit organization that assists Native American communities in economic development, when he met with CTUIR leaders. He’s watched the Tribes grow over the last three decades.

“I was always impressed with Umatilla,” says Stainbrook. “Over the years I’ve been watching the progress. When the Tovey boys showed up things started to move.” Dave is now the director of Nixyaawii Community Financial Services; Bill is the director of the CTUIR Department of Economic and Community Development; and Al manages Wildhorse Casino.

“Over the years I’d put them in the top five tribes in the country for aggressively regaining lands as well as using the land for tribal economic development.”

Getting fair market value

In the mid-‘90s the CTUIR created its land-acquisition program. It initially purchased land using money from mitigation funding to Tribes for the loss of land, including wildlife habitat, caused by dams on the Columbia River, and the Bonneville Power Administration for salmon recovery. A percent of gaming revenues from Wildhorse Resort & Casino as well as bank financing and contract sales has also been dedicated for land purchases.

Of the Tribes’ 43,393 acres of fee property purchases, 21,688 acres were paid for with mitigation funding and 21,705 acres using Tribal money.

Integrated planning: Blue Mountain foothills rise above the Confederated Tribes’ major crop: wheat. Photo by Walters Photographers

Bob Burns, an accredited rural appraiser, has been working for more than 50 years as a farm and ranch appraiser. He’s worked with the CTUIR staff in the Land Acquisition Program for several years.

“They know what they’re doing and if they don’t they ask direct questions of the right people,” says Burns.

Burns notes that the Tribes try to purchase land at fair market value but are often faced with a higher asking price.

“A lot of people take a run at them with a price that’s way too high. They think because the Tribe has a casino they can ask a premium,” Burns says. But staff in the Land Acquisition Program “talk to people one on one and it usually comes down to the price of the appraisal; the real fair market value is what the Tribes do.”

Funding the buy-back

The Land Buy-Back Program was created as a result of the settlement in Cobell v. Salazar. In the late 1990s, Elouise Cobell, a Blackfeet Indian from Montana, sued the Bureau of Indian Affairs for 100 years of inadequate accounting of compensation owed Indians for leases.

The trial lasted a dozen years and Cobell died before she could see the creation of the Land Buy-Back Program, which is funded by a settlement of $3.4 billion.

A total of $1.5 billion is being distributed to current Tribal-member landowners based on the value of the property and income that could have been produced over the last century.

Historic division: I-84 cuts through Umatilla Reservation lands. Photo by Maryellen McFadden/Creative Commons

Funded by the other $1.9 billion in the settlement, the Buy-Back Program set aside funding for tribes throughout Indian Country to reduce fractionation—that is, land that through inheritance is often owned by hundreds of Indians, many from different reservations.

The Umatilla Tribes received about $20 million in two allocations as their share of the $1.9 billion but expect to get more, according to Bill Tovey. This has helped the Tribe purchase almost 13,000 highly fractionated acres of land within the Reservation.

To address fractionation, in 2008 the Umatilla Tribes updated their inheritance code, which now requires that when a landowner dies their land can only be passed to CTUIR members. Each year the Tribes spend around $700,000 on land in program that has no CTUIR heirs. Purchasing that property is no easy task. In some cases, hundreds of owners—many from other Northwest reservations—share in small parcels.

Tovey knew of one parcel of slightly more than a third of an acre owned by more than 20 Indians. In those instances, the CTUIR has issued checks for pennies, especially if the parcel is rangeland, which is valued lower than productive farmland.

MORE: Environmental justice at Hanford: Reconnecting Indigenous people to their land

Of the 33,953 acres of Trust land purchases, the Tribe has bought 15,788 acres from willing sellers, 5,495 acres through probate and 12,670 acres with the Land Buy-Back Program.

Tovey says the CTUIR is well on its way to realizing the land acquisition vision set out by his brother in 1990.

“The CTUIR has been very aggressive with land acquisition,” Tovey says. “The staff has grown from one in 1990 to 10 people who work on acquisitions, probates, fee to trust, land management and data collection. Gaming revenues and mitigation funds have helped push the ball further with the Land Buy-Back Program giving the Tribe big bursts of funding to secure lands.”

Wil Phinney recently retired after 24 years as editor of the Confederated Umatilla Journal, the award-winning monthly newspaper on the Umatilla Indian Reservation in eastern Oregon. He lives in Pendleton, Oregon.

Pat and Ric Walters have owned and operated Walters Photographers, a portrait studio in Pendleton, Oregon, for 30 years. Pat is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and enjoys photographing the people and land of the CTUIR.

READ MORE INDIGENOUS ISSUES STORIES.

The Collins Foundation is a supporter of Columbia Insight’s Indigenous Issues series.