A growing group of influencers is promoting the idea that incentives, not mandates, is the best way to get hunters to start using non-toxic ammunition

Spot the difference? A mix of calibers and brands, each of these boxes contain lead-free ammo. Photo by Andrew McKean

By Andrew McKean. March 4, 2021. After 35 years evaluating them, Lynn Tompkins can tell pretty quickly what malady brought eagles, hawks and owls to her bird rehabilitation center just south of Pendleton, Oregon.

Charred talons are a sign the bird tried to roost on high-tension power lines, including the web of wires that radiates away from hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River. Impact injuries like broken wings are commonly caused by collisions with cars, picture windows or wind-turbine blades. Others come in with gunshot wounds. Lacerated heads and legs generally suggest encounters with domestic pets or wire fences.

But a surprising number of raptors come to Tompkins’ Blue Mountain Wildlife with no external injuries at all. Instead, they’re lethargic, disoriented or have clenched talons that make them teeter like amputees.

Many of these birds are brought to the rehab center by game wardens, bird watchers or passersby who thought the dazed birds didn’t look or act right, and managed to nab them in fish nets or winter coats. The fact that a bird of prey—among the most unapproachable of our wildlife species—can be captured at all suggests it’s not particularly fit.

Birds that arrive at Blue Mountain with no obvious injuries are immediately poked with a syringe. Tompkins wants to test their blood.

Lead victim: This golden eagle arrived at Blue Mountain Wildlife with critically high lead levels. “We started chelation immediately, but could not save the bird,” says executive director Lynn Tompkins. “It died the next day.” Courtesy of Blue Mountain Wildlife

“Any bird that comes here in a box, you can’t tell much about it until you look at its blood,” says Tompkins, 68, executive director of the rehab center she runs with her husband, Bob, and a few technicians. In the decades she’s been receiving injured raptors from a three-state area—Idaho, Oregon, Washington—Tompkins continues to personally handle a lot of birds in boxes.

“A blood test will tell us if there is elevated levels of lead in their system,” says Tompkins. “Over the years we’ve learned to test every eagle that comes in, and most buteos [large hawks]. You have no idea if they have lead or not, but a blood test tells you what you have to do next.”

Often lead levels, measured in micrograms per deciliter of blood, are so high the bird must be euthanized. Non-lethal lead levels can often be treated with what’s called chelation therapy, the injection of special chemicals that bind to lead in an animal’s bloodstream and allow it to pass it through their urine over the course of days of treatment.

After years of having to mail blood samples to a lab, waiting days to get the results, and then more days to apply chelation therapy to her avian patients, Tompkins says donors have outfitted Blue Mountain with blood-testing and lead-remediation equipment, so she can do most of her work in-house.

There’s more work all the time.

“It’s amazing what you find if you look,” says Tompkins. “Because we’ve found over the years that otherwise asymptomatic birds often have lead, now we look for it. And we often find it. Nearly all the eagles we get in have some detectable level of lead in their blood. About a quarter of all great horned owls have lead, and it’s pretty widespread in hawks and falcons.”

Tompkins is quick to cite the likely source of lead in birds’ bloodstreams: hunters’ bullets, which scavenging birds ingest from gut piles and carcasses. But she’s just as quick to note that she’s not anti-hunter or hunting.

“Most hunters don’t want to harm wildlife,” Tompkins says. “In most cases, they don’t know the effect they’re having. Our job is to educate them, and hopefully help them make informed choices.”

Spreading poison

Ultimately, Tompkins wants hunters to stop shooting lead. Most don’t know the effect their bullets have on the food chain.

Traditional hunting bullets—those made of a lead core bonded to a thin copper jacket—are designed to expand on impact with their target. These bullets kill with a combination of penetration through soft tissues and expansion, ensuring that the maximum amount of trauma is delivered by transferring energy from the bullet into the animal.

One of the problems with lead is that it fragments fairly easily—much more easily than solid copper bullets, leaving shards and putty-like remnants of lead around the wound channel. Fragmentation can actually be measured by weighing recovered lead bullets and comparing the spent weight with the weight of unfired bullets. Several studies have concluded that even when the majority of the lead bullet passes through an animal, fragments often remain in both the entrails and the meat.

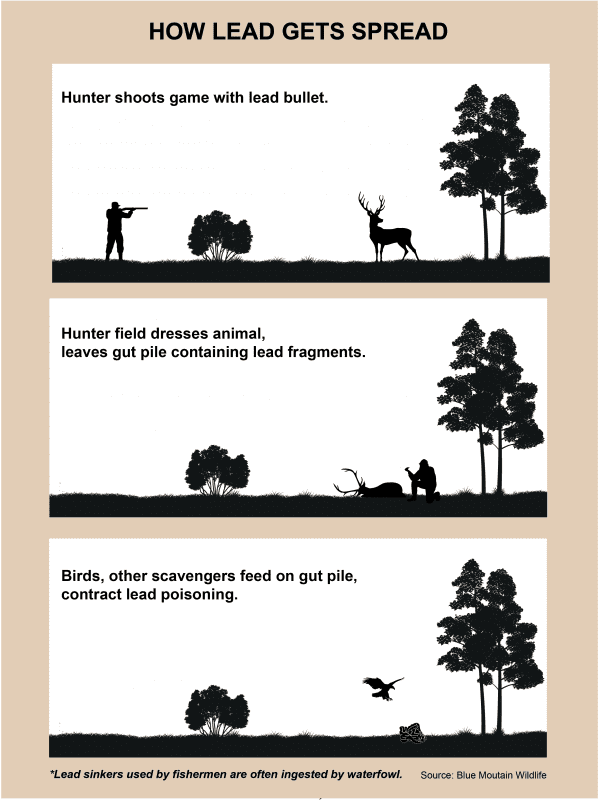

It’s those fragments that often end up in the gullets of scavengers, who eat from the carcasses or gut piles left behind by hunters who field dress animals. The more lead fragments that are ingested, the greater the impairment on the neurology and motor skills of not only raptors, but also secondary species such as magpies, ravens and crows.

Tompkins says there’s a precedent for hunters making informed choices when it comes to the ammunition they shoot. She points to the transition hunters made starting in 1987, when lead shot was banned nationwide for waterfowl hunting based on studies that showed high mortality from ducks and geese that ingested spent lead pellets in shallow marshes. The prohibition was phased in over three years, and now the use of non-toxic shot for duck and goose hunting is normal.

Tompkins thinks big-game hunters can make that same transition, even without the cudgel of law.

Blue Mountain Wildlife has encouraged the use of non-toxic ammunition for hunting elk on Zumwalt Prairie near Enterprise, Oregon, where the state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) issues some 1,000 cow tags annually. Hunters who volunteer to use non-lead ammunition are entered into a drawing for prizes valued at several thousand dollars.

MORE: Elk numbers decline in Zumwalt Prairie

The incentives, promoted by the Nature Conservancy (which owns a big chunk of Zumwalt Prairie), the Oregon Hunters Association, Boise-based The Peregrine Fund, ODFW and the Oregon Zoo, have resulted in about 70 percent of Zumwalt elk hunters using non-lead bullets. This presumably exposes far fewer raptors to lead poisoning.

Tainted meat?

There’s still a lot of carcasses in the Columbia River Plain created every year by hunters shooting lead ammunition. Oregon and Washington report about 5,000 mule deer are taken by rifle hunters in units on both sides of the river each fall.

Fragments from lead bullets are often left behind in gut piles. It’s those remains that Tompkins says poisons scavenging raptors, which are particularly susceptible to lead poisoning because their highly acidic digestive systems dissolve lead along with putrid meat and rancid entrails.

Non-toxic bullets, generally made from solid copper, don’t fragment as easily as lead, and any copper fragments that do remain in gut piles and are consumed by scavengers have negligible health impacts.

What’s inside? After field dressing deer, hunters leave behind gut piles often laced with toxic lead fragments. Photos by Chuck Thompson

If lead fragments can end up in gut piles, how about in the deer and elk meat hunters take home? A 2008 study from North Dakota, in which donations of hunter-harvested venison to food banks revealed lead fragments in about half the samples, alarmed hunters. But members of the North American Non-Lead Partnership are not focused on risk to human health.

“We’re not medical doctors,” says Chris Parish, director of global conservation for The Peregrine Fund. Instead, he says, “our focus is preventing potential exposure in scavenging wildlife.”

MORE: Mystery bacteria is killing bighorn sheep in Eastern Oregon

Measuring the effect of ingested lead in humans is complicated. Some studies show elevated lead levels in hunters; others claim that because humans’ digestive systems are less acidic than birds, we don’t metabolize lead easily.

Most sources say that because the science is contentious, we’re better off looking at known victims of lead: scavenging birds.

The California mistake

The most vocal advocate for getting the lead out of ammunition in Columbia River country is Leland Brown. Burly and bearded, Brown is the non-lead hunting education coordinator at Oregon Zoo, and a founding member of the North American Non-Lead Partnership, which aims to wean hunters off lead-based ammunition.

Brown is by now accustomed to the fact that any discussion of getting the lead out of our fields and forests comes with sharp political overtones. Second Amendment groups claim ammunition restrictions are tantamount to gun control. They frequently point to California as proof of their point.

California lawmakers started phasing out lead ammunition back in 2013, citing harm to endangered California condors from environmental lead. A total statewide ban on lead ammunition—for target shooting, small-game hunting, all bird and big-game hunting—took effect in 2019, making it a criminal act to possess or shoot lead ammunition. Brown was one of several non-governmental educators tasked with teaching California’s hunters and shooters how to transition to non-toxic bullets and shotshells. It’s not an experience he cares to repeat.

“I point to California as an example of what not to do,” says Brown, who since 2015 has tried a voluntary, incremental approach to getting hunters to consider alternatives to lead ammunition. “Hunters were openly hostile to what was a top-down mandate in California, which they considered a tactic to end hunting and shooting altogether, and we’ve seen widespread lack of compliance as a result.”

Lead-free: Leland Brown is the founding member of the North American Non-Lead Partnership. Courtesy of Leland Brown

In Oregon, Brown wants to approach the topic collaboratively and incrementally, in the hopes that incentives can do what lead-ammo prohibitions couldn’t: allow hunters to take responsibility for their decisions.

MORE: Wolverines break through … finally!

He points to successes the Non-Lead Partnership had in northern Arizona and southern Utah—inside the range of the California condor—where big-game hunters were asked to consider using non-toxic bullets. Once they were educated about impacts of lead on condors and other birds, nearly 80 percent made the switch. Their decision was accelerated by offers of free non-toxic ammo, but Brown says the conversion is based on a shared desire to be stewards of wildlife and wild places.

“I begin conversations reminding people that we’re all hunters,” says Brown. “At the [Non-Lead] partnership, we love to hunt, and we want to hunt more. But in order to do that we have to protect what we love by promoting sustainability and stewardship, which are core values of hunters. One way to do that is to reduce the lead that we introduce to the environment. We can talk about the science all we want, but we’ve found that the best way to get the point across is to show them.”

In pre-COVID times, Brown and other members of the Non-Lead Partnership hosted field days at which they invited shooters and hunters to see for themselves—by shooting different loads—how lead bullets fragment and leave shards of metal in their targets.

For hunters, lead ammunition has numerous appealing attributes, including lower price, widespread availability and consistent performance, whether on big game, small game or targets. But non-lead ammunition, generally made of copper, can be just as accurate and effective on game, says Brown, who says that non-toxic loads are becoming more available and competitively priced every month. In February, industry leader Vista Outdoor, which owns the Remington and Federal Premium brands, announced the acquisition of Oregon-based Environ-Metal, makers of Hevi-Shot, the oldest non-tox waterfowl loader on the market—a sign that the big boys of the ammo world see the market changing.

Many of Brown’s field days ended with attendees getting coupons for free or reduced-price “non-tox” ammunition. The Non-Lead Partnership hopes its efforts are the start of an ammunition conversion, and at least one fewer problematic deer or elk carcass on the landscape.

Why lead still rules

The fact that hunters need to be incentivized into conversion indicates the scope of the problem. Despite narrowing the supply and price gap, copper bullets remain scarcer and more expensive than lead.

Partly, that’s a legacy of centuries of ballistics. Malleable, abundant and hard-hitting (thanks to its density), lead has been a favored projectile since the catapult era. It’s fairly cheap to produce—many commercial bullets are cast from lead sourced from recycled batteries—and performs well in a wide variety of firearms.

MORE: 16 and counting … Inside a Washington community’s war on cougars

Copper bullets, meanwhile, must be precisely milled from bar stock. And, because copper is about a third lighter than lead, non-toxic bullets of the same grain weight as lead must be longer, which can make them finicky to shoot in older rifles.

Bottom line: while availability of non-tox ammo has increased and prices have dropped, it’s still more expensive than lead and can be hard to find. And one of the fallouts of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a run on guns and ammunition, presumably as confidence in American institutions and social norms have eroded in some communities. That means the ammunition industry is currently working double-time to make the most popular bullets, which are made of lead.

Jon Zinnel, conservation and youth shooting sports program manager for Vista Outdoor, which in addition to the Federal and Remington lines also owns CCI, a large ammunition manufacturer in Lewiston, Idaho, says the industry is accelerating alternatives to lead. But he acknowledges non-toxic options are slower to get to consumers in the current ammunition market.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Most of what happens to them, we’re responsible for, either directly or indirectly.”—Lynn Tompkins, Blue Mountain Wildlife[/perfectpullquote]

One of Zinnel’s customers is California hunter Ryan Newkirk, who hunts deer, birds and small game around Paso Robles. He’s seen firsthand what happens to ammunition supplies when lead is outlawed, as it was in California. The state’s first lead prohibitions were intended to protect endangered condors; eventually the blanket ban was imposed statewide.

“When the lead-free mandates came down, I was worried about the expense and availability of compliant ammo, but I’ll tell you, the fact that California led the charge led to a lot more options, and the price differential is narrowing,” says Newkirk. “My issue isn’t actually with big game. Monolithic bullets work great on deer and elk. My problem is with upland birds and with small game and varmint hunting.”

Newkirk says lead-free shotshells for doves and quail are relatively ineffective.

“I hate to wound and lose a bird because the ammunition isn’t up to the job,” he says. “And if you think that people are going to spend $2 a shell to shoot non-tox for doves … c’mon. They’re either going to quit hunting doves or they’re going to break the law and shoot lead.

“The industry simply hasn’t made a non-toxic .22 load that’s effective for small game like rabbits and ground squirrels. I worry about the hunter-recruitment problem with that. If you take away the ability for a beginning shooter to have success with a .22—the gateway caliber for new hunters—then you are effectively crippling hunting, whether it’s intentional or not.”

Newkirk says blanket prohibitions on lead ammunition for all hunting as well as target shooting—as California has done—will result in people either quitting hunting or turning them into reluctant lawbreakers.

Resistance to regulation

Back in Oregon, Leland Brown is worried by precisely the dynamic Newkirk describes. He’s seeing legislation come out of both Salem and Olympia that would ban lead ammunition in Oregon and Washington, respectively. In Oregon, Senate Bill 592 would ban lead in fishing tackle and ammunition. In Washington, House Bill 1346, killed in the 2019 session, would have criminalized the sale or gifting of lead ammunition to anyone under age 21.

Tough love: Chris Parish is director of global conservation for The Peregrine Fund. Photo courtesy of Chris Parish

The legislation puts the Non-Lead Partnership in a tight spot. While members generally applaud the intent, they’re deeply worried about implementation, and compliance.

“I think we have to go slow,” says Brown. “We have to use anecdote, word-of-mouth and education, not legislation. This is like the adoption of any new technology. There are the early adopters who are on the leading edge. Then there’s the early majority and the late majority, and then the never-wills on the tail end. It’s your standard bell curve. Our job is not to change that curve, but to help people through it more efficiently so that the transition is painless.”

Brown further notes the partnership is interested in getting lead out of all animal carcasses, not with prohibiting lead ammunition for target shooting.

“One of the fundamental rules that we teach in hunter education is that hunters must know their target and beyond before they pull the trigger,” says Brown. “That really hit me when it comes to shooting an animal when its remains can be part of the food chain.

“We need to know our target, but the beyond is what remains after I leave the field, whether it’s a deer or a rabbit or a quail. If we’re talking about an animal that can become food for us or for another animal, then we need to be thinking about the downstream consequences of lead.”

Back in Pendleton, Tompkins has the same concerns.

“It’s because I feel responsible, I guess,” she says, when asked why she devotes so much of her life to rehabbing raptors. “Most of what happens to them, we’re responsible for, either directly or indirectly. And I feel that if I get to enjoy the beauty and the majesty of an eagle or a hawk, then I need to take some responsibility for them. Besides, what we do to our environment, we do to ourselves. It’s just that we can see it more easily in a sick hawk than in ourselves.”

“How lead gets spread” infographic by Mackenzie Miller.

[…] As in other areas where condors are now living in the wild, the biggest threat would come from potential poisoning from spent lead ammunition. […]