‘Cold water refuges’ are increasingly crucial for migrating salmon and steelhead. But what exactly are they?

Seeking shelter: Salmon migrating through the Columbia River Basin have never had it easy. Now the annual spawning epic has become even more perilous. Photo by BLM

By Chuck Thompson. July 23, 2020. Water in the Columbia River Basin isn’t just getting warmer. In places it’s getting downright hot.

At the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima rivers in southeastern Washington, for instance, summer water temperatures have been recorded as high as 90 F (32.2 C).

Blame dams, levees and other concrete additions to the river. And, of course, climate change.

All salmonids—chinook, coho, sockeye, steelhead—suffer if the water they live in spikes above 68-70 F. Anything above 70 F (21 C) increases stress and the likelihood of fatal diseases.

In water above 74 F (23.3 C) salmon stop trying to swim altogether. At that point, many will die.

Swimming in warm water requires fish to expend fat stores and burn more energy than they otherwise would.

As a result, by the time they reach spawning grounds, gonadal functions may be impaired or fish may simply be too exhausted to spawn.

So what’s a migrating salmon or steelhead to do when confronted with a warming Columbia River?

What is a ‘cold water refuge’?

For salmon and steelhead moving up the Columbia River in summer—when water temperatures above 70 F are now commonplace—the answer to an increasingly inhospitable river lies in a relatively recent behavioral adaptation.

In growing numbers, salmon and steelhead have begun seeking relief in small pools of cool water. These pools form at points where mountain rivers and creeks feed into the Columbia.

Scientists call these areas of naturally occurring thermal relief “cold water refuges” or CWR. They’re sometimes referred to as “thermal refuges,” “thermal sanctuaries” or simply “refugia,” but each term describes the same thing.

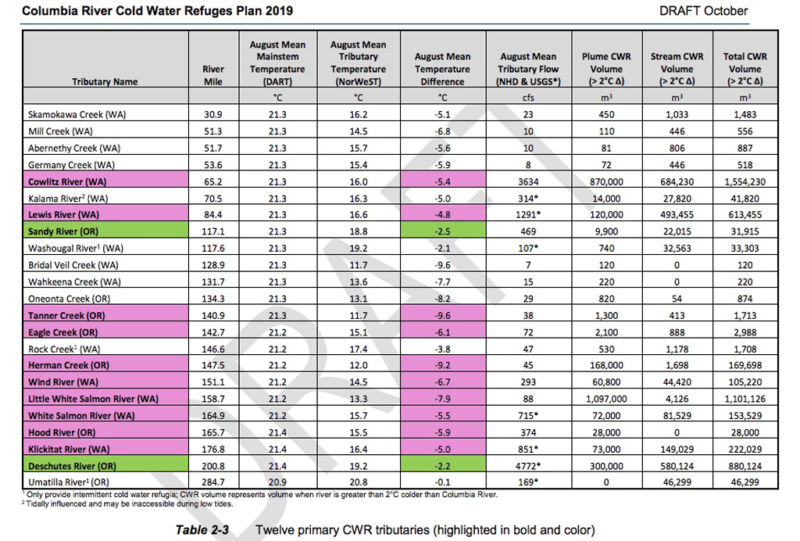

Arranged by river mile, the EPA’s list of all 23 cold water refuges on the lower Columbia River. The Cowlitz River is the largest by total volume. The 12 primary CWRs are highlighted in color. Courtesy EPA

Get used to that acronym. CWRs have become critical pit stops for migrating fish. Chances are you’re going to be hearing a lot more about them.

“These refuges are really telling about the way adult salmon are using habitat in the Columbia,” says Margaret Neuman, executive director of the Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group, in Ellensburg, Washington. “There’s this idea that they’re hopscotching up the river from cold-water input to cold-water input.”

Dashing dozen

Researchers became aware of the importance of CWRs in the Columbia River in the 1990s. Studies led by teams from the University of Idaho in the early 2000s established the current baseline of scientific knowledge about them.

But a 176-page EPA report due at the end of summer 2020—the Columbia River Cold Water Refuges plan—will shed light on just how crucial CWRs have since become to salmon and steelhead survival.

The report is certain to become the touchstone document for assessing CWRs in the Columbia River.

In the lower Columbia—the stretch from its mouth at the Pacific Ocean to its confluence with the Snake River some 325 miles upstream near the Oregon-Washington border—EPA researchers assessed 191 sources of water input into the Columbia.

Of these 191 tributaries, just 23 qualified as CWRs—meaning the water they drain into the Columbia flows at high enough volume and significantly colder temperature to make a localized impact.

Of these 23 CWRs, 12 were identified as “primary” CWRs.

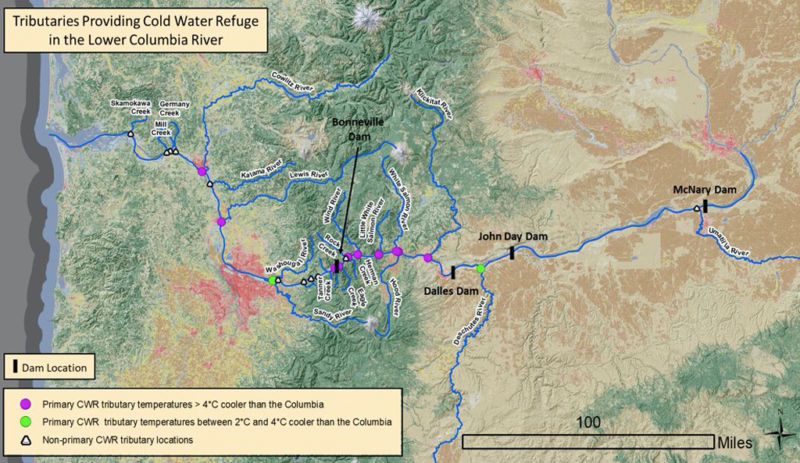

Primary CWRs are unevenly distributed. Past the Deschutes River (the most easterly green dot) fish find little relief. Courtesy EPA

How important are these 12 primary refuges? Collectively, they constitute 97% of the total CWR volume on the lower Columbia River.

The two largest are located at the mouths of the Cowlitz River (river mile 65) and Little White Salmon River (river mile 159), which empties into Drano Lake prior to entering the Columbia River. Both rivers are in Washington. (See map above for location of all 12 primary CWRs.)

Perhaps the most astonishing find by researchers is the way salmon and steelhead are altering historic patterns of migration to dash from CWR to CWR on their way to upriver spawning grounds.

“During the peak CWR use period—late August-early September—we estimate that 80-85% of the steelhead in the Bonneville Reach between Bonneville Dam and The Dalles Dam are in CWR, which is 0.2% of the total volume of water in this reach,” says John Palmer, senior policy advisor at the EPA Region 10 office in Seattle and the new CWR study’s primary author.

In other words, when temperatures are warm the majority of migrating fish aren’t even bothering with most of the Columbia anymore. They’re simply seeking out rare breaks from its punishing heat and regrouping before racing to the next refuge.

Adaptive research

Although the current vernacular isn’t widespread, “cold water refuges” have always been a feature of river hydrology.

So how do researchers know salmon and steelhead along the Columbia haven’t always sought out CWRs as R&R stops along their grueling journeys?

“The Columbia historically wasn’t as warm as it is now,” says Palmer. “Summer temperatures were about 2-to-3 degrees Celsius less, so it didn’t get to the temperatures that we know trigger refuge use. The University of Idaho (studies) found that at 19 C some fish use them, but when you get to 21 C you have almost 70% of steelhead moving into cold water refuges.

“At 21-22 C, those are thresholds the science says fish want to escape that water. Putting two and two together we concluded the amount of use we see today is an adaptation to the warmer river. The evidence is highly suggestive that’s what’s happening.”

Enough cold water left?

Starting in the 1930s, dams and the slackwater they produce have warmed summer temperatures in the Columbia River by about 2 degrees Fahrenheit, according to the EPA. Climate change has additionally warmed the river by a little more than 2 degrees Fahrenheit.

Conditions will get worse. Across the Columbia River Basin the trend is warmer water.

“There’s only so much cold water,” says Palmer. “It gathers in winter and spring but slowly gets flushed out of the system (as summer progresses).”

So, given current models are there enough CWRs to accommodate the needs of migrating fish?

In the lower Columbia, probably so.

High heat: Fed by tributary creeks originating from elevations of up to 8,000 feet in the Malheur National Forest, the John Day River is still too warm at its confluence with the Columbia to provide thermal refuge. Photo by BLM

East of the Cascades, however, rivers and streams flowing into the Columbia are generally warmer. That’s where the situation gets dire.

“We’re still examining the question,” says Palmer. “There are no refuges above the Deschutes River (river mile 201). So fish have to go from there past the John Day Dam up through the 76-mile John Day Reservoir. It’s the warmest stretch of the river and there’s really nothing there for them to escape those temperatures.”

During hot summer months, between the John Day Dam and McNary Dam (river mile 292) there are no CWRs at all. In warm years the river here can average 72 F (22 C) in August. The 10-year average is 70.7 F (21.5 C).

Just below the McNary Dam, the Umatilla River can be considered a CWR only after late August and September, when it begins to run slightly cooler than the Columbia.

The Umatilla would need substantial upstream restoration to reestablish flow and lower its temperature before it could supply meaningful thermal refuge to fish in the hottest weeks of summer.

Waters begin to cool, if gradually, after the Columbia’s northward bend into Washington and eventually British Columbia.

From fire to frying pan

CWRs might sound like a welcome relief for salmon and steelhead. But any benefits they derive from CWRs are mitigated by a massive drawback.

CWRs don’t just attract fish. They attract fishermen.

“Fishermen know these areas because that’s where fish go. But they don’t refer to them as ‘refuges.’ They call ‘em ‘fishing holes,’ right?” says Palmer.

Refugia researcher: EPA’s John Palmer. Courtesy of John Palmer

Fish in a kettle is an apt analogy. There’s a reason large CWRs, such as Washington’s Drano Lake, attract commercially guided fishing expeditions from as far as Yakima. Anglers know their chances of landing fish increase in compact areas where fish cluster.

A 2009 study found migration success among steelhead that used CWRs was about 8% less than steelhead that didn’t use them. Fishing in CWRs explained the decreased survival rate.

It’s a cruel twist for migrating species. Fish are seeking cool refuges; in response, humans have made these refuges even more dangerous than the warm waters fish are so desperate to escape.

Palmer stresses the purpose of the coming EPA report is to provide information, not suggest mitigation efforts.

“We’re not in the fish-regulation business, we’re in the water-quality business,” he says.

Nevertheless, the agency’s forthcoming report will likely inform future conservation strategies.

“People in the salmon recovery world doing projects in these tributaries can help justify a project by saying, ‘Well, not only are we going to increase spawning and rearing habitat in the tributaries but it’s helping to cool the water, which will have a beneficial effect down river.’ People doing projects will think about this as an objective,” says Palmer.

Management policies have already been influenced by the evolving significance of CWRs.

Hot spot: Salmon and steelhead seek relief in the cool waters of Drano Lake. Fishermen await. Photo by Jurgen Hess

In 2020, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife closed all fishing during warm months at what the department calls “thermal sanctuaries” at the mouths of Eagle Creek, Herman Creek and the Deschutes River. The closures are in effect from July 15-September 15.

The EPA’s report could help build a case for more protections around CWRs.

Enhancement projects

Although cold water refuges occur naturally, efforts to enhance them are popping up around the Columbia River Basin.

The Portland-based Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership (LCEP) is currently in the assessment phase of a thermal refuge enhancement project at the confluence of Oneonta and Horsetail Creeks on the lower Columbia River.

“The concept is to construct one or more diversion structures that will promote expanded cold water plume formation by diverting warmer Columbia River water away from the confluence zone,” says LCEP physical scientist Keith Marcoe.

Feature attraction: A manmade alcove in the bank helps retain cool spring-water at the Yakima River Mile 25 Thermal Refuge. Photo by Eric McCrea

In 2019, near Benton City on the Yakima River, the Mid-Columbia Fisheries Enhancement Group (MCFEG) reconnected a small, cool groundwater spring to the river. It’s likely the Yakima River Mile 25 Thermal Refuge is the first such enhancement project on the river.

Coupled with downstream projects currently in development, the goal is to capitalize on critical sources of cool water in what the organization calls a “very hot portion of the Yakima River.”

“The spring is already naturally there; we’re trying to maximize how much positive impact it’s having on the river,” says MCFEG executive director Neuman. “We basically dug a little alcove into the bank …and added wood and planted trees along the spring area to try to keep the water cool. We installed (structures) to hold the spring-water back, just not let the spring-water all run off at once, but try to modulate it a little bit.”

A beaver has since settled in the area—beaver ponds can enhance cold water refuges—but it’s too soon to gauge the project’s long-term impact.

Manmade CWRs?

Such small-scale interventions lead to a broader question: are large-scale manmade cold water refuges possible?

Although created unintentionally, artificial CWRs already exist along the Columbia River.

Government Cove, where Herman Creek spills into the Columbia River just east of Cascade Locks, Oregon, was created when small islands in the river were artificially joined. The result is a protective barrier that collects and delays the flow of cool water from Herman Creek before it empties into the mainstem of the Columbia.

“It wasn’t built to be a cold water refuge but it’s turned into that,” says Palmer. “The cold water stays there for a while, and fish go into it.”

By far the largest and most used refuge, Drano Lake, east of Stevenson, Washington, is another unintentional refuge. The lake was created when a dike was built at the mouth of the Little White Salmon River to accommodate railroad tracks, and later State Highway 14.

“That already is kind of an artificial CWR,” says Palmer. “So it’s not impossible to think about doing some of this.”

How much help, really?

Among some environmentalists, CWRs are increasingly seen as an important piece of salmon recovery strategies.

Is that hope misplaced? Is human enhancement of CWRs a too-little-too-late solution to the Columbia’s epic problems?

“From our perspective, the problem with temperature in the Columbia and Snake is that the whole river is too hot,” says Miles Johnson, senior attorney for Columbia Riverkeeper. “I don’t mean to say that cold water refuges are not important and worth protecting. But the lower Snake and lower Columbia are too hot for salmon and steelhead and it’s dams and reservoirs and climate change (causing the problem).”

The implication is only large-scale solutions can fix the large-scale problems in the Columbia and Snake.

Steelhead standard: Oregon DEQ defines cold water refugia as “those portions of a water body where … the water temperature is at least 2 degrees Celsius colder than the daily maximum temperature of the adjacent well mixed flow of the water body.” Photo by Jurgen Hess

Especially considering their vulnerability to fishing, Palmer admits the overall value of CWRs is “a big question.” But he’s more bullish on their role.

He points to a modeling study conducted at an EPA lab in Corvallis, Oregon. In a theoretical Columbia River in which all CWRs were removed, the simulation showed stress levels in salmon and steelhead more than doubled.

“In the lower Columbia the salmon have told us cold water refuges are helpful for them; it’s mitigating the warmer Columbia,” says Palmer. “I don’t think they would be going into cold water refuges if there wasn’t some benefit there.”

Chuck Thompson is editor of Columbia Insight. Additional reporting by Valerie Brown.

Excellent read Chuck! Ed Jones, ADF&G Juneau

Very informative discussion.It is very useful for every people.you should post more about this matter.

starvapedubai

Thanks Chuck for identifying these important remaining refuges. I worked on salmon recovery planning for 10 years in the Columbia Basin. These cold water refuges have likely always been important to salmon. However, I always wondered why we continued pursue expensive technical solutions to salmon recovery when we continue to harvest endangered species and produce millions of hatchery fish that compete with wild populations. The reasons for salmon and steelhead decline are numerous, but what would happen if we just stopped fishing and producing hatchery fish for at least a generation? Other than fish and wildlife agencies would collect less money from licenses.

After reading this article that has showed how the salmon have adapted and is surviving the changes in water temp and the obstacles that are far from structural that happen do to act of nature ,weather, flooding ! The cooling holes that have been identified are well talked about but I’m sure there are other people that have possibly the same few questions that I have and about to ask! The reason for these few questions is how much they are related to this article and to ask why we haven’t removed 100% unnecessary slowing of water flow and at the same time have stopped the movement or ability of the the salmon to use the creek to finish the reason they have returned ! What’s up is what I have to ask why would we raise the temperature by stopping the water flow and interfere with the salmons ability to spawn ! Why would we interrupt eagle creek and the one creek you have failed to even mention that has had the highest scores of any creek in oregon for quality of water or however you state those facts (Mill Creek) and about 5 miles up this creek there is a dam that has been more damaging than any other section of this creek ! Why would we not fix these simple problems that have never needed to have in these creeks ! And yes I have a couple more questions in relation to fall chinooks run up the Columbia for another day! Mill creek OR!