Transmission development is the biggest obstacle to renewable energy goals. The Bonneville Power Administration is moving on a major initiative

More, please: The power grid is evolving to include intelligent controls, distributed computing, automation and other new technologies. It also needs to grow. Image: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

By John Harrison. September 26, 2024. Building new high-voltage transmission is expensive, complex and complicated, but without it compliance with government clean-energy mandates will be difficult to achieve—maybe impossible.

In July, the Bonneville Power Administration announced a plan to move ahead with more than $2 billion in multiple high-voltage transmission substation and line projects necessary to reinforce the transmission grid that connects the Pacific Northwest with the American Southwest and points east.

“These projects are intended to increase capacity and accommodate regional growth, as well as an abundance of new, clean energy resources,” the agency said in a statement. “The projects must undergo environmental review and, if constructed, would support thousands of megawatts of renewable energy added to the power grid and help Oregon and Washington customers meet 2030 clean energy targets.”

Six projects would reinforce existing major Bonneville transmission lines that run from east to west, boosting the capacity of the lines to move electricity from the east side of the region—Montana, eastern Idaho—west to load centers such as the Puget Sound area and Portland.

These projects, combined with a handful of smaller projects near Seattle and Portland, would reinforce transmission lines that deliver electricity to utilities and large industries that are Bonneville customers in those areas.

Early estimates are that the projects collectively would cost approximately $1.35 billion with expected energization between 2025 and 2032.

If all are energized, they’d provide at least 6,000 megawatts of additional capacity on Bonneville’s transmission network.

In addition, Bonneville is working on four projects in Central Oregon, where utilities are experiencing significant demand growth and are attracting large commercial customers.

These projects consist of one new transmission line and three substations.

Collectively, these are estimated to cost $839 million and could accommodate new service for incoming large customers and regional load growth while maintaining high transmission reliability.

“Big-money issue”

Transmission adequacy is an issue across the West, where states, utilities and local governments have adopted clean-energy policies in response to the impacts of climate change.

The goal is to improve the capacity of high-voltage transmission, and thus help steadily move the electricity supply away from generators that burn fossil fuels to new and existing renewable energy, particularly wind and solar power.

While transmission is an unlikely topic for casual conversation among friends, it has the attention of those utilities, utility organizations, environmental groups and government agencies that either transmit power or have an interest in it.

This is not a trivial matter. It’s a big-money issue rife with complexities such as siting issues (where to build new lines) and litigation, particularly litigation over environmental impacts such as protection of habitat for threatened species like sage grouse.

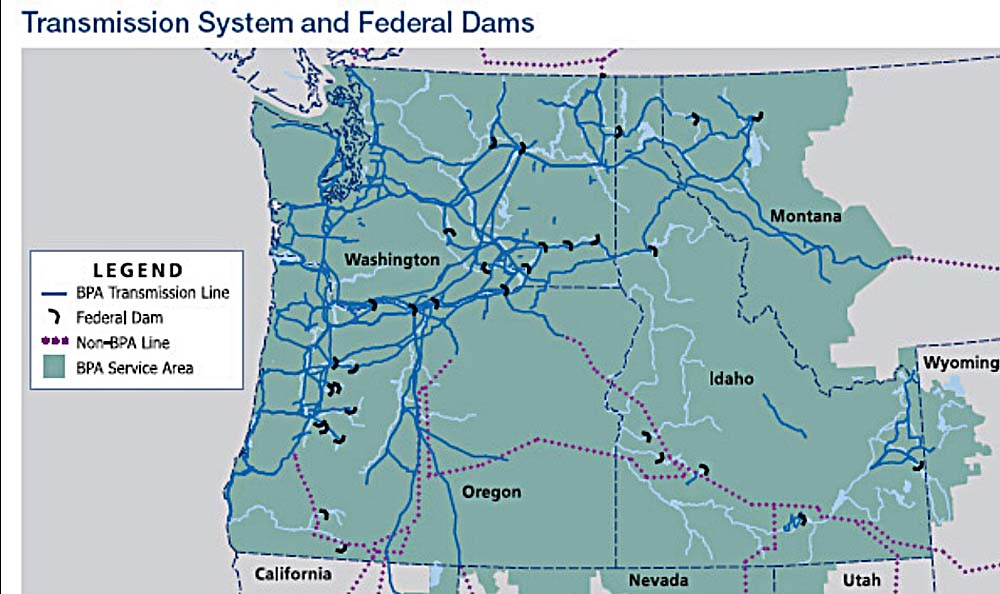

The Bonneville Power Administration’s 15,000+ miles of high-voltage lines account for 75% of the PNW’s grid. But blank spots exist east of the Cascades where renewable energy is being produced. Map: BPA

For example, the beginning of construction of a new line through eastern Oregon to eastern Idaho has been delayed for years over actual and potential litigation regarding issues including location of the line, property owners’ unwillingness to sell rights of way, and impacts to sage grouse habitat and the historic Oregon Trail.

Another problem is the current system of contracting for access to transmission. This archaic system sometimes leaves lines fully contracted but not fully utilized.

Separate from the projects announced in July and others announced earlier this year, the BPA also is beginning to study demand in the Mountain Northwest high-priority transmission corridor for accelerated transmission expansion.

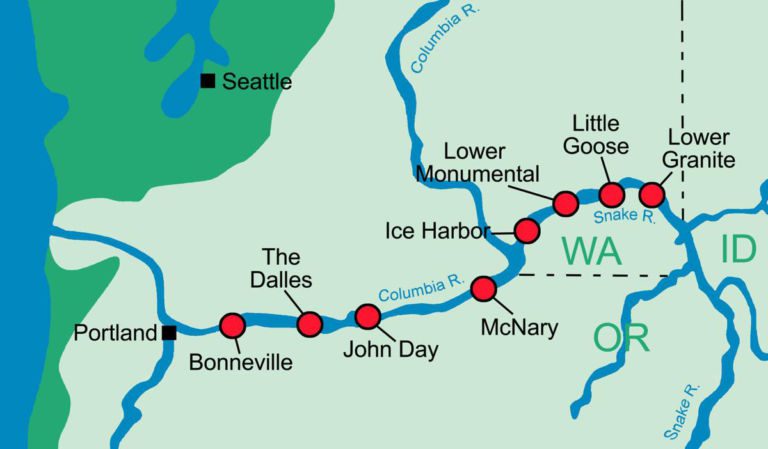

The Mountain Northwest high-priority transmission corridor, designated by the federal Department of Energy in May, is a corridor 1,500 feet wide and 515 miles long, running from The Dalles to Nevada. It’s one of 10 high-priority transmission-planning areas in the country.

The DOE designation identifies the 10 areas as places where new transmission capacity is needed to help move anticipated new electricity, such as from wind and solar in the West, from generation to load.

The designation is intended to speed federal planning and construction of new lines in areas where line congestion currently is a problem, or will be.

Unanimous call for better planning

At an online transmission planning seminar in August, Ravi Aggarwal, the BPA’s director of regional transmission planning, said the agency’s intention for the Mountain Northwest corridor hasn’t been finalized.

But he said additional lines in the corridor, where there already are high-voltage lines, could be an alternative to congested lines including the Pacific Northwest/Pacific Southwest Intertie lines that connect the Northwest to utilities in Southern California.

At the seminar, Rich Glick, a former chair of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), said that a nationwide FERC order issued in 2015, Order No. 1000, which reformed FERC’s electric transmission planning and cost allocation requirements for public utility transmission providers, “was a big success in the sense that … it really addresses what was almost the unanimous call for better and anticipatory transmission planning.”

Transmission adequacy is an issue across the West.

In addition to streamlining the transmission planning process—FERC has to approve new lines—Order 1000 also called for transmission planners to consider alternatives to new lines.

These so-called “grid-enhancing technologies,” which Bonneville relied on for its 2015 transmission improvements in the Interstate 5 corridor, could include, for example, upgrades to substation and grid-control technologies to allow existing lines to carry more power.

While Glick admitted that “some of these new projects are going to be costly,” grid-enhancing technologies, also known as non-wires alternatives, hold out the possibility of what he called “ways to stretch the dollar to utilize existing assets more efficiently [and] to avoid building some new projects.”

The seminar was hosted by the Seattle-based energy and fish and wildlife newsletter Clearing Up.

In his opening remarks at the seminar, Clearing Up Editor Steve Ernst said, “Transmission development in the West is now the biggest hurdle to reaching state renewable energy goals and maintaining reliability in the West. It’s become clear that an historic build-out of transmission—both long-haul transmission lines connecting the Intermountain West to load centers along the coast, and shorter projects around densely populated urban areas, will be needed to meet both the short- and long-term clean-energy mandates.”

Thanks John and team.

Does this plan include replacing the current heavy steel wire with up to date carbon fiber?

In siting wind and solar farms for alternative energy, do FERC, BPA (and similar power providers nationwide), and local Power Utility Districts (PUDs) have any approval role? For endangered species, do EPA or state environmental agencies have any approval role? Or is the siting of such “farms” more of an opportunistic agreement between a willing landowner and solar or wind corporation?

It would seem that optimal and cost-efficient planning and building out an electric grid would need regulation and control of the siting of alternative energy generation.

This is a good introduction to a huge, complex, and contentious issue for Oregon. Several years ago wind and solar farm developers identified transmission capacities as a problem for implementing the HB2021 clean electricity requirements, and HB3630 in the 2023 session directs the Oregon Department of Energy to develop an Oregon Energy Strategy to identify sufficient pathways for generation, storage, and transmission projects, among other tasks. There are multiple agencies and groups developing such plans or sub-plans, with a variety of motivations, various incomplete collaborations, and various levels of transparency.

I believe that the largest stakeholder group–residential and commercial power customers–has not been sufficiently represented in these discussions. Solar arrays on residential and commercial roofs and over parking areas will continue to get cheaper and not require big transmission lines to get the power where it’s needed for resilience. Several days of household energy storage will soon be a standard feature on electric vehicles, which will also get cheaper and cheaper. Combinations of distributed generation and storage can be accessed by the grid as virtual (distributed) power plants (VPPs); there are about 500 VPPs operating in the US, but Oregon has zero. One problem is that we only reward utilities for investing in big energy plants and transmission lines–an increasingly obsolete business model.

I agree completely. I just visited a cousin who has a complex of buildings running off grid on just two rows of panels. They have batteries to store the power and they also can use their truck battery for bi-directional power. It’s expensive, but if the utilities would incentivize or at least not de-incentivize residential

solar it would be more fair to the folks further East who are expected to sacrifice for our power needs out West. In any case we will have to upgrade the transmission system. No

way around that. I hope they can come up with a plan that destroys as little as possible of our natural resources, and creates energy generating shade on the giant parking lots (and rooftops) throughout the Willamette valley.