Maintaining the beauty and productivity of its orchards required citizen action. And still does

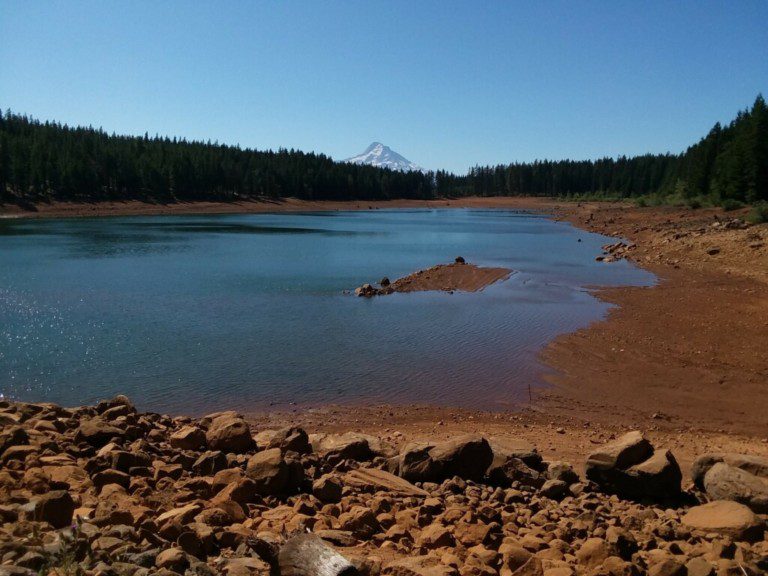

Fruit preserves: Mount Hood viewed from Mount Hood Organic Farms in Oregon’s Hood River Valley. Photo: VWPics via AP Images

By Richard Benner. September 21, 2023. A remarkable thing happened in Oregon in 1973. The Oregon Legislature sent a bill to Governor Tom McCall creating the nation’s first statewide land use program. It aimed to protect farmland and stop urban sprawl.

Fifty years later the slogan promulgated around the U.S. by Travel Oregon bears repeating: “Extraordinary is Ordinary.”

Travel other states and you’ll see the difference: productive farmland just across the “urban growth boundary” from condos, apartments and subdivisions.

In other states, houses sprawl across the rural landscape and render farming impossible or impracticable.

Bordering the Columbia River Gorge on the northern border of the state, Hood River County was one of the first beneficiaries of the new land use law.

For scores of years the Hood River Valley has produced some of the best pears in the world.

It’s blessed with highly productive soils and ample water. As more acres were planted, packing houses and other farm infrastructure popped up in Odell, Pine Grove and Hood River.

Today just under 16,000 acres in the small valley are covered by fruit trees: apples and cherries, but mostly pears—to Homer, pears were the “gift of the gods.”

Overall, the Pacific Northwest produces about 84% of the fresh U.S. pear crop each year, valued at almost $300 million in 2021.

The fight for farms

Fruit trees bear more than fruit.

They bear blossoms in the spring, before the fruit forms. The blossoms turn an already beautiful valley into a spectacular landscape.

People come from afar to admire the blossoms.

Why we fight: Green Bartletts are the most common summer/fall pear in the Pac NW. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

Blossom festivals take place in the towns of the valley and the Columbia River Gorge.

Some tourists find the valley’s beauty irresistible. They want to enjoy it more intimately, to buy a tract of land and build a house among the orchards.

One result is conflict with orchards.

New residents who don’t understand farming complain about noisome orchard practices across fence lines. They drive up land prices and make acquisition of parcels out of the question for orchardists.

The conflict broke into the open in 1977. Developers proposed a “planned unit development” near Parkdale in the upper valley, acre and half-acre residential lots.

The county planning commission put the question to voters: development or farm zoning?

The pending vote spawned one of Oregon’s first county citizens’ organizations devoted to protection of farmland: the Hood River Valley Residents’ Committee (now Thrive Hood River).

Many committee members were orchardists. The committee roused support for agriculture, which prevailed in the referendum.

Then a new player entered: the Mount Hood Meadows Corporation (MHM), owner and operator of a downhill ski area on Mt Hood.

Well aware of the beauty and attraction of the upper valley, MHM waved the vote aside and gained approval from the county board of commissioners for a 450-unit resort complex near the orchards.

The Residents’ Committee went to the new state Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) to upend the county decision. Turning to the new statewide land use planning goals, LCDC overturned the county decision in 1979.

Same old: No billboards, malls, resorts or housing sprawl. Preservation of the Hood River Valley is no accident. Photos: Thrive Hood River/History Museum of Hood River Co/Darryl Lloyd

A second push by MHM two years later was rebuffed by the county planning commission.

Elections to the county commission of two opponents of the resort persuaded MHM to withdraw its application.

Pears and the growers had prevailed: today, there is no resort in the upper valley.

Uncertain future

Early resistance by county governments to the new state land use laws dissipated over time.

Zoning to protect farms has been in place in Hood River County for decades and offers growers a degree of certainty for their investments.

But weak points in state law still bring not only new houses not occupied by farmers, but also “non-farm” uses into farm zones— campgrounds, junkyards, solar-energy generation, landscape businesses, kennels, water bottling operations, contractors’ equipment yards, community centers and dozens more.

Pickathon: Orchard in the Hood River Valley. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

Other challenges have emerged.

Operational costs for farmers have risen. There are local pickers, but not enough. Many orchardists have to bring pickers in from Mexico.

A drying climate makes irrigation more expensive.

Increasingly, pears and other tree fruits grown in the valley compete in an international market. The prices growers receive are often determined by crop harvests in California, Poland or China.

The average age of farmers in Oregon continues to climb. Their children—and younger people in general—are deterred by the hard work and uncertainties.

Despite these challenges, there’s reason for optimism. Growing world population and rising incomes will increase consumption of tree fruits. And Hood River pears are still among the finest in the world.

I was there at the time these events occurred in the early eighties, and was friends with one of the newly elected county commissioners at the time: however I never knew this back story. I guess I was too young and innocent. Thank you for this reporting. It has filled in a significant piece of my own past.

I thought Medford was the pear capital.

It’s unfortunate that like so many articles extolling Oregon’s agriculture – and particularly the beautiful Hood River Valley – that little mention is made of the human costs. For instance, each spring the local FISH Food Bank announces the arrival of the cherry orchard workers. Why? Because they come to the food bank to get food, not earning enough to buy food for themselves and their families. Other groups will do fundraisers to purchase long-sleeved shirts to protect orchard workers from pesticide expsoure. Meanwhile, as tariffs and costs squeeze farmers, many (but not all) are advocating for changes to land use to allow them to add in wedding venues, retail operations, and more. And while adoption of more effective irrigation has helped reduce water consumption, fertilizer and pesticide runoff still makes its way into local streams, groundwater, and rivers. The recent fight in the Oregon legislature over farm stand regulations makes clear that there isn’t a unified view on any of the challenges.