A new book by Eli Francovich brings overdue calm to one of the West’s most emotional debates. It’s time to listen

What do you see? Perhaps no animal stirs as many primal emotions, and points of view, as the wolf: Photo: Idaho Fish and Game

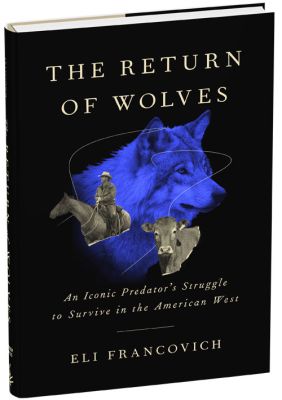

June 8, 2023. Below is an abridged excerpt from The Return of Wolves: An Iconic Predator’s Struggle to Survive in the American West, a new book by journalist and Columbia Insight contributor Eli Francovich. The book is earning well-deserved praise and generating discussion for its evenhanded examination of one of the Columbia River Basin’s most hotly argued environmental issues. The Return of Wolves is available for purchase from Timber Press and wherever books are sold. —Editor

In September 2019, I met Daniel Curry on a hot and dusty day high in Washington’s Kettle Range, hemmed in by thick walls of young pines and wandering cattle. I was touring wolf country with a rancher, a politician, and a biologist all stuffed into a beat-up truck.

I’d been covering wolf news for two years for the regional paper. It was one of the many issues I was expected to keep tabs on, but unlike other beats, I never felt I had a handle on the topic. Instead, I felt I was mindlessly repeating talking points from both sides of the debate.

When caught in the middle of two opposing viewpoints, the normal recourse for a reporter is to find the perspective that most closely represents the middle ground. For issues of wildlife and ecology, this often means speaking with professional biologists and wildlife managers. The prevailing wisdom is that this kind of reporting helps balance out the extreme views.

So I’d attempted to do just that. And yet, I still felt like I had an inadequate understanding of the debate. My reporting had been charged with being anti-wolf. It had also been maligned as being pro-wolf.

“Why don’t you do your research?” angry readers screamed at me, saying that I was misrepresenting the current science of wolf ecology.

The politician I was now riding with had called me late one Friday, spitting mad, alleging that a recent story I’d published had been utterly divorced from the reality on the ground.

All of this disturbed me. Not the anger or criticism, because for a reporter those are as natural and expected as layoffs and pay cuts, but rather the sneaking suspicion that I was missing some bigger, more interesting and important story. While I dutifully recounted the facts, I couldn’t help but wonder if there was a more nuanced, compelling, and challenging tale lurking beneath the surface.

The Return of Wolves is published by Timber Press.

I didn’t know it then, but I was experiencing the natural limits of rational and reductive thinking. Facts and the scientific process are invaluable tools, but when it comes to looking at the issues where people, animals, and culture intersect, they often fall short.

This is not unique to the Wolf Wars of northeastern Washington. It is present in any discussion that, intentionally or otherwise, pits questions of science against questions of belief. We see it in the politicization of the coronavirus. Likewise with climate change. Both are issues of fact that have become terribly divisive, largely along lines of belief. And it seemed to me that there was perhaps no better metaphor for this fundamental tension in contemporary American behavior than the story of wolves returning to Washington.

So I decided to line up a tour of wolf country with three folks I hoped could help me shake off some of my confusion about this particular story. A rancher who had lost cattle to wolves. A politician who represented ranchers but also played in the halls of power. And a biologist who worked on the ground and seemed to know wolves and people well.

After three hours with them, it felt like little had changed. Over coffee, each of my companions had reiterated points and perspectives I’d heard before. They all came across as sincere and honest people, but each of them was also clearly entrenched in their way of thinking.

Then we set off in the truck, taking a series of Forest Service roads winding up into the hills. The rancher recounted times he’d stared down wolves, hand on gun. The biologist talked about the biological complexity of the canids. The politician decried the decisions that urban liberals make, how little they understand rural reality. We stopped occasionally to take photos, or to look at some cows standing by the road, their tails languidly whipping back and forth.

And then, at the tail end of the day, eyes heavy from the heat and the early start, we passed a horse trailer parked in a dusty turnout. Two tents were pitched in the dirt under the blazing sun. Behind them, a banked hill led up to thick trees. A large tarp had been stretched between the thickest pines, and two horses occupied the only shade it provided.

We stopped and jumped out of the truck. A lanky man with shortly cropped hair, faded cowboy boots, filthy pants, and one gleaming pistol on each hip approached us.

He wanted to know what we were doing. Who we were. Why we were there. This is how I met Daniel Curry.

Later I would learn that Curry is a range rider, a job that requires him to spend most of the year in the woods trying to keep wolves from killing cattle and cattle from wandering into the mouths of wolves. He works for the biologist with whom I was traveling. His days roll with the seasons.

He works in rugged country, country choked with pines after decades of fire suppression and clear-cutting. Here, he patrols sections of the 1.1 million-acre Colville National Forest on behalf of ranchers who release their cattle onto the land every spring and demand their safe return in the fall.

He spends weeks at a time in isolation, his only company a menagerie of animals (three dogs and three to four horses), working odd hours, heading into the hills at 9 p.m. on some days and 3 a.m. on others. Typically on horseback (but sometimes on an ATV), he searches for cows and looks for wolves and tries to disrupt the natural outcome of such meetings. He talks about wolves with evident affection, even wearing a ring embossed with the silhouette of a wolf.

Despite that, his most consistent point of human contact is with the ranchers whose cattle he guards. These are men and women who don’t wax poetic about the howls of wolves. Politically and socially conservative for the most part, ranchers generally see the natural world as a God-given resource to be used for the betterment of humans. A worldview anathema to Curry, who speaks fondly of individual animals as “beings” worthy of respect and care, regardless of their utility to Homo sapiens. His best friend, I would find out, is his horse Griph.

Larger than life: Francovich has written about wolves several times for Columbia Insight, including a 2021 story that examined a controversial Idaho law aimed at reducing the state’s wolf population. Photo courtesy F4WM

I didn’t know any of this that dusty afternoon, but I sensed in Curry a good story—the coveted fuel of any journalism—and a level of honesty and an air of open-mindedness that I found refreshing after spending the day listening to the usual talking points. He was guarded, but friendly.

“I’m busy now,” he said, “but why don’t you come back tonight? We can chat more.”

And so that evening I drove back into the woods.

Amidst the dirge of ecological decline, the return of wolves to the lower forty-eight has been a major chord in a chorus of minors. Their return from near-extinction after decades of focused assault is a remarkable conservation and cultural success story.

In 1995 and 1996, biologists released thirty-one wolves into Yellowstone National Park. The canids, which had been relocated from Canada, multiplied and spread. Bolstered by similar releases in Idaho and Wyoming, the population grew. Over the following decades, wolves made their way throughout the West, inhabiting territory and habitat that hadn’t seen the apex predator since their local eradication one hundred years earlier.

News of their resurgence provoked a whole spectrum of reactions. For scientists, wolves represented a singular opportunity to observe, in real time, the consequences when a long absent predator returns to an ecosystem. For activists, the return of wolves was a clarion call for conservation. For some ranchers, hunters, and farmers, wolves became a prime example of government overreach and an attack on their values and way of life. For journalists and artists, here was simply a good story that tapped into primal fears and ancient iconography.

Most of the attention was focused on the wolves living in one of the largest remaining tracts of undeveloped land in the contiguous United States: the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Anchored by the eponymous national park, it encompasses parts of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. By landmass—between 20,000 and 35,000 square miles depending on where you draw the lines—the ecosystem is larger than eighty-six countries. What’s more, the states bordering this wilderness are lightly populated and politically homogenous, with a combined population of approximately 3.5 million people.

In 2008, when the long-legged lopers reached Washington State, they encountered a landscape sundered largely along geographic lines. West of the Cascade Mountains, the Evergreen State is humid, urban, liberal, and increasingly wealthy. East of the divide, it’s dry, rural, and increasingly poor. The political beliefs of nearly eight million Washingtonians can roughly be predicted by where in the state they happen to call home.

The wolves arrived from the east and the north—migrating from Idaho and Canada—and their population remains concentrated in the eastern half of the state. And so, every summer for the past decade and a half, when cattle head out to graze the public lands located primarily in Washington’s rural, politically conservative, and poorer counties, wolves will kill some of them.

Ranchers cry out, saying their livelihood and culture are under attack. In response, state wildlife managers will take to the air in helicopters and kill wolves.

Environmentalists and wolf advocates protest and file lawsuits, arguing that cows are a nonnative species and ranchers are grazing their cattle on public land for a nominal fee. The threats fly in both directions. Wolf meetings are canceled due to threats of violence. The FBI gets called. Wolves poached. Pelts smuggled to Canada, a bloody FedEx package the fateful clue. A state lawmaker suggests sending an environmental activist a severed wolf tail and testicles. In short, wolves incite the kind of passions usually reserved for war and infidelity—passions that highlight deep political and social divides.

Newcomer: This photo of a collared gray wolf dubbed WA109M was taken by a trail camera earlier this year in Klickitat County, documenting the return of wolves to southwest Washington. Photo: WDFW

That passion for wolves—both negative and positive—means that wolves get all sorts of media attention and money. Environmental groups milk outrage over the killings of wolves to assist their fundraising efforts. Cattle producers’ associations do the same, buying up billboards in eastern Washington featuring the image of a snarling wolf and a tagline urging folks to call the sheriff. State agencies employ multiple biologists focused on Canis lupus, even while more endangered species—sage grouse, for instance—are lucky to have a single fulltime employee studying them. Some of that focus comes from ignorance. And some of it comes from misplaced passion, or pure and simple greed.

But I believe that the primary tension underlying the Wolf Wars is one that’s common to all human-nonhuman relationships: the problem of coexistence. Do we have the will and wisdom to coexist with nonhuman animals? That question is particularly pressing in a state like Washington, one that jams humans and animals together. And while Washington may be unique in the United States now—with its dense human population surrounded by wild animals—it likely won’t stay that way.

Consider other less populous Western states like Montana and Idaho. Their populations are booming, with people moving into lands once roamed by bears, grizzlies, bobcats, coyotes, wolverines, fishers, and, yes, wolves.

At the same time, larger, more populous (read: more liberal) states that long ago killed their native predators have been clamoring for a touch of wilderness. Colorado has drawn up plans to reintroduce wolves. Meanwhile, California’s ongoing rewilding efforts have led to a healthy and surprisingly urban cougar population, and a pack of gray wolves recently arrived in Plumas County along the Nevada border.

The story is similar abroad. In 2015, wolves returned to the Netherlands for the first time in more than a century. Rewilding efforts across Europe are bringing long-absent species back onto a continent that has been manhandled by humans for thousands of years.

In all of these cases, wild animals are coming into contact with highly altered landscapes that demand adaptation and resilience on their part.

And yet, the true burden of coexistence will fall upon humanity’s collective shoulders. One hundred, two hundred, or four hundred years ago, the answer would have been simpler: move or kill the wild animals. That is no longer a viable approach, as there is no longer an “elsewhere” to which to move these animals.

At home on the range: Daniel Curry in January 2021. Photo: Eli Francovich

Ironically, and perhaps tragically, as humans move farther from the world of rain, snow, and wind, our desire for a return to the wild—powered I believe by a deep genetic nostalgia— is renewed. And yet, most of us don’t have the faintest idea what that kind of life requires.

From Republic, Washington, a charming albeit decidedly weathered former gold rush town, Curry’s camp was an hour drive away. Belying stereotypes about rural life, Republic collects an astonishing array of people: old hippies clinging to the ghost; young back-to nature types driving banged-up Subarus through washed-out roads; conservative-minded ranchers, loggers, and miners who have seen their ways of life dry up as natural resource extraction has ended in much of the United States; at least one family of immigrants from India.

After fueling up I drove back into the hills to meet up with Curry. We talked late into the evening, drinking by the fire.

The rancher with whom I’d been riding earlier joined us. Whiskey loosened his tongue and I learned that he’d shot and killed a wolf days before in self-defense. Curry flinched at this revelation but said nothing. This rancher, after all, had agreed to try and live with wolves, a minor miracle in eastern Washington. After several hours of drinking and talking, he went on to confess that he kind of liked hearing wolves in the hills.

Beneath the nearly full moon, someone pulled out a steel drum, and we howled into the night, hoping for a response. None came and in the morning, I returned to Spokane, the second largest city in Washington, where I live and write for the newspaper. I published a story about Daniel Curry and range riding.

Life rolled on, but something stuck with me about Curry’s quixotic mission. Perhaps it was the doomed romanticism of all those years spent alone in the woods, away from people, defending an animal that most will never see. I was struck by the immediacy of that work. Of the challenge of trying to balance human interests and need with nonhuman interests and the difficulty of bridging the rural and urban divide. After all, Curry believes that the wolf wars are simply a symptom of a bigger problem: the widening political and cultural divide in the United States. Striking a balance in wolf land would go a long way toward kneading the “dough of society” back together, he told me.

“This place has the chance to work out,” he says. “It could be a good example. Or it could all fall apart.”

Wonderful story, thanks.