A chrome-bright coho salmon rockets up a shallow stretch of river. Photo by K. King, USFWS

Against the odds, the Nez Perce tribe is coaxing coho to return to their ancestral river.

By Valerie Brown. Feb. 6, 2020. Pacific salmon are under threat throughout their native range. Looking at the Columbia River Basin alone, most stocks are either vastly reduced or past the point of no return. 106 runs of anadromous fish have already gone extinct in the Basin, leaving approximately 40 percent of the region’s rivers devoid of one their greatest resources.

These are desperate times, indeed, and desperate measures have already been taken — perhaps nowhere more notably than on Idaho’s Clearwater River, where the Nez Perce are restoring habitat, developing innovative hatchery methods for coho salmon, and bending a few rules in the process.

Tribal members, scientists, wild fish advocates and river managers in the Pacific Northwest have long wrestled with how to respond to the decline of these complex animals. And it’s been a hot-button issue in the region since before the 1980s, when those same groups finally started admitting that salmon were going to disappear altogether without some major changes in human behavior.

But for the Nez Perce, “letting fish not survive is not an option.” So says Becky Johnson, the tribe’s leading coho expert.

500 miles away from home

Not surprisingly, the Basin’s most severely affected salmon populations are those that have to negotiate upwards of 500 miles of river and traverse eight dams to reach their spawning grounds. This includes all of the salmon populations native to the lower Snake River, the Salmon River, and the Clearwater River in Idaho.

A map showing the traditional territory of the Nez Perce that was ceded to United States (light green), the current boundaries of the Nez Perce reservation (dark green), and the entire Columbia River Basin (dark tan). Map courtesy of CRITFC

And looking specifically at coho salmon in the Clearwater, records show that the species disappeared before they even had a chance to be classified as endangered or threatened.

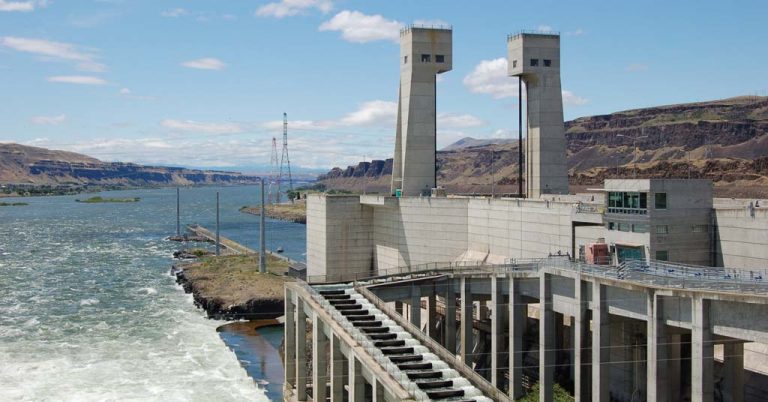

It was the dams — particularly the Lewiston dam, built in 1927 — that sounded the death knell of the Clearwater coho, which were officially declared extirpated in 1985. Chinook and steelhead were also devastated and remain threatened or endangered today. (The Lewiston dam isn’t there any more, but it was replaced by four newer dams on the lower Snake.)

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game tried and failed to reintroduce coho into the lower Snake system in 1962. And during the late 1970’s, Snake River coho were considered for inclusion in the Northwest Power Act, which obligates utilities to mitigate the harm done to fish in the Columbia basin. But by that point it was too late. The fish were already gone.

In the early 1990’s, however, following a decade that was ruled by pessimism, there was renewed interest in preserving and recovering salmon stocks in the region. This interest was fueled, in part, by the four tribes that refused to give up their traditional fishing rights in the Basin: the Nez Perce, Warm Springs, Umatilla and Yakama.

In 1994, the Nez Perce took decisive action to bring coho back to the Clearwater. But the tribe faced a major hurdle from the start: there were no coho native to the river available to serve as a broodstock. So the tribe got half a million coho eggs from federal hatcheries on the lower Columbia (below Bonneville dam). Idaho Fish and Game officials did not approve of the Nez Perce project, Johnson says. But the chance to get such a big batch of coho eggs was enough to inspire the tribe to truck the eggs all the way to the reservation without a long-term plan or a transport permit from the state.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“We out-planted those coho under threat of arrest,” Johnson recalls.[/perfectpullquote]

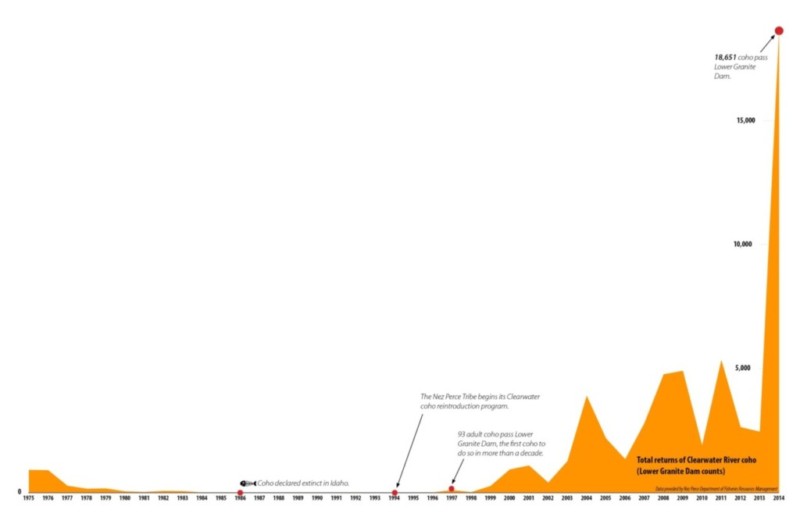

Fast forward 20 years, and in 2014 the tribe and the State of Idaho were able to open a tribal- and sport-fishing season for coho for the first time in Idaho history. The number of returning fish that year reached 18,651. Numbers have dropped since then, but the tribe continues to work toward a sustainable fishing season, which would require about 14,000 fish to return every year.

This graph shows dramatic comeback of coho in the Clearwater. Graph courtesy of CRITFC

Idaho’s official attitude has mellowed considerably since 1994. According to the state’s chief of fisheries, Jim Frederick, “We’ve been excited to see how successful that program has been. It’s just beginning to provide some great opportunities for tribal members and recreational [fishing]. I give them a great deal of credit.”

It’s complicated

Because the salmon life cycle is so complex, reestablishing a population anywhere is dicey. To survive, salmon have to be able to adapt to a wide range of surroundings, from beaver ponds to vast rapids to slack water reservoirs to saltwater. This is one of the reasons why coming up with a workable management policy is so difficult. On their journey from their natal streams to the Pacific and back again, the fish utilize floodplains, wetlands, meandering streams, fast-moving water, brackish estuaries and open ocean.

Salmon are also adapted to micro-environments when spawning. “We started with fish from the lower river that didn’t have to pass any dams, and moved them 500 miles from the ocean,” Johnson explains. The first returning fish had to be able to make the return trip on their own, perhaps drawing on some genetic memory of ancient spawning grounds.

And it seems to be working. “Even though they have a tough time, we’re seeing thousands of fish return as compared to when there were none,” Johnson says.

There has long been controversy over the role of hatchery fish and their negative effects on wild populations. Wild fish survive the ocean phase of their lives far better than hatchery fish, but as Johnson says: “You’ve got to be able to use the tool that will increase survival. And we wouldn’t be able to do this program without hatcheries.”

“If we didn’t have the dams we wouldn’t need the hatcheries,” she adds.

There is also recent research showing that some differences between wild and hatchery fish are epigenetic – related not to different genes but to different gene expression – suggesting that hatchery fish might be able to up their game and recover the behaviors of their wild cousins under the right conditions.

A male coho displays full spawning colors while digging a redd in its natal stream. Photo courtesy BLM

The Nez Perce program is aimed at sticking as closely as possible to the wild genotype. “We take wild fish into the hatchery for broodstock and have hatchery fish that go out into nature to spawn,” says Johnson. Thus the most robust hatchery fish that have made the round trip can then be used for a new broodstock — wilder, at least, if not truly wild.

The ghastly gauntlet

Even with carefully tended hatchery and wild populations on the Clearwater, there are many factors beyond the tribe’s control. Migration presents a ghastly gauntlet for all anadromous fish and water temperature is becoming a major problem. (Currently, the water behind the Dworshak dam is released in the summer months to cool the Snake River for adult fish returning from the ocean.) These fish have to traverse multiple reservoirs, encountering native and introduced predators, including sea lions, walleye and smallmouth bass. Ocean conditions also vary dramatically according to cyclical patterns such as the North Pacific Oscillation and El Niño/La Niña.

Elephants on the table

Most, but not all, stakeholders acknowledge that the single most effective action to help coho (along with all of the other migratory fish in the Columbia Basin) would be to take out as many dams as possible. “Recovery is near impossible without freeing up the lower Snake,” says Bert Bowler, a fisheries biologist with Snake River Salmon Solutions.

Of course, the four dams on the lower Snake were built with federal money, so it will take federal permission — and funding — to remove them. And while Bowler believes removal is a distant prospect, Johnson is optimistic. “There will be a day when they come out,” she says. ”At some point the cost to maintain and take care of them as they age will outweigh the benefits.”

It can’t happen fast enough for the fish, because, as Bowler points out: “The elephant in the room is the rate at which climate change is overtaking us.” Restoring salmon habitat and free-flowing rivers may be the only hope of giving salmon a robust enough environment to survive the looming stresses of drought, heat waves, warm water, crashes in prey populations, and ocean acidification.

But as the story of coho in the Clearwater shows, the bond between people and fish can be surprisingly deep. Johnson, a native of Leavenworth, Washington, thought she wanted to be a physical therapist when she started college. But when a biology professor arranged a summer project for her with the local tribe, Johnson says she “was hooked.” She took a job with the Nez Perce straight out of college and has never looked back. She believes the tribes will never abandon the coho, chinook, steelhead and lamprey they are nursing back to vitality.

“I thought if anybody was going to fix this problem, the tribes will, because they care so deeply,” Johnson says.

“They’re like the protectors. Having fish for them is like breathing.”

Photo courtesy of the Oregon Dept. of Forestry. (Click here to watch an underwater video from Alaska’s Campbell Creek)

Great writer, great story. Everyone should pass it on!