The views and opinions expressed in the following essay are those of the author alone, and they do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Columbia Insight.

By Dac Collins. June 27, 2019. On Friday, June 14, over 150 people gathered on the banks of the Columbia in southeastern Washington to participate in the first annual Hanford Journey. Down around the bend from them — a quick flight for a cormorant — a shuttered nuclear reactor towered above the surrounding sagebrush. Standing out like a corpse at a cocktail party, the B Reactor’s presence served as a stark reminder of why demanding a thorough cleanup of Hanford is just as necessary today as it was 30 years ago.

Sponsored by Columbia Riverkeeper and the Yakama Nation Environmental Restoration and Waste Management (ERWM) Program, The Hanford Journey celebrated the legacy of the late Dr. Russell Jim, a Yakama tribal elder who founded the ERWM program and dedicated his life to giving Native American tribes a voice in the Hanford cleanup.

Photo by Dac Collins

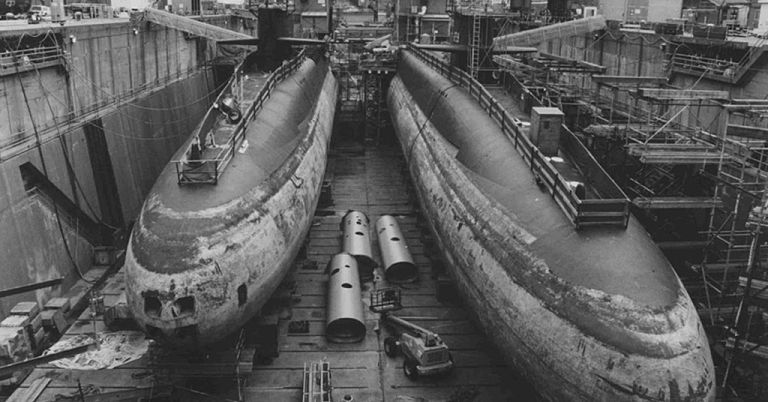

Dr. Jim was born on Yakama Reservation lands in 1935, just four years before Hitler invaded Poland and kicked off the deadliest war in modern history. Six years old when the United States joined World War II, Jim would have been around eight years old in 1943, when the U.S. War Department decided to locate portions of the Manhattan Project along the Hanford Reach of the Columbia. (The ancestral home of the Wanapum Tribe, this stretch of river is still an archaeologically and culturally important site for other tribes in the region, including the Umatilla, Nez Perce and Yakama.)

76 years later, history books remind us that the weapon produced with B Reactor plutonium ended World War II, ushering the United States into a period of global dominance and affluence that continues today. But it remains difficult for us to comprehend the scope of environmental degradation and dehumanization that the Hanford Nuclear Site has wrought on the Columbia River and its people…

…not to mention the moral implications of the U.S. government’s decision to use that B Reactor plutonium on the people of Nagasaki. And regardless of whether or not you agree with that decision, it’s toxic legacy — the routine exposure of Hanford workers to radiation and the continued poisoning of the river and its inhabitants — proves that some of the catastrophic damage caused by Fat Man has been self-inflicted.

The damage control continues to this day, as a species with an average life-span of 79 years confronts a man-made element with a half-life of 24,000 years.

Last year, the U.S. Dept. of Energy announced a proposal to reclassify some of the high-level radioactive waste at the Hanford Reservation as lower-level waste. And just weeks ago, the DOE issued new rules giving itself the authority to abandon storage tanks with more than 100 million gallons of high-level radioactive waste at Hanford. Meanwhile, continued research shows that radioactive groundwater plumes continue to threaten the health of the river, and the Oregon Dept. of Energy admits that “chromium, nitrate, uranium, technetium, tritium and strontium have all reached the Columbia River” — all of which threaten the last remaining stretch of the main stem where fall chinook spawn in significant numbers.

In light of these continued challenges, the Hanford Journey was a rallying point for those who carry on Dr. Jim’s advocacy work. Participants included Yakama Nation elected officials and tribal members, legislators, agency representatives and citizens from all over the Pacific Northwest.

Polly Zehm, Deputy Director of the Washington Dept. of Ecology, shared some of the lessons she learned from Jim, including his advice “to stop thinking about the Columbia River as something separate from us people…to think of ourselves as part of the river, and to think of the river as part of ourselves.”

Jim’s niece Natalie Swan, who works as a botanist for the tribe, also gave a speech, as did Yakama Tribal Chairman JoDe Goudy.

“I’m not here to hurt anyone’s feelings…and I refuse to be held responsible for anything that comes out of my mouth,” Goudy began, launching into a searing speech that framed the historical context of Hanford. He focused on the underlying threads of deceit and domination that can be traced back to the European conquest of the Americas, and through landmark cases of the 19th and 20th centuries to the present-day.

“So when we get into a discussion of how Hanford came to be, of what happened historically to essentially exert a modern-day dominating and dehumanizing act such as the inception, the origin, the continued existence and the challenges with regard to cleanup of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation,” he continued, “I try to understand what has happened to build us up to the history of the present moment.”

And referring to the “sacrifices that have been endured by this land, by this water, by the different entities and resources, and by the peoples that were affected,” the Chairman posed an important question to the crowd: “Are we truly discussing this thing in the proper context?”

Silent as stones, the participants listened on while the big river flowed past. Caddisflies danced on its sunlit surface as it ran eastward, moving toward a thing that can be explained and contained but can never be undone.

Photo by Kiliii Yüyan