[/media-credit] Rep. Mark Johnson (far left) leads an energy forum in Hood River Sept. 2015. From left: Jay Ward, Energy Trust of Oregon; John Gernstenberger, Hood River Electric Co-op; Gary Bauer, Northwest Natural; Varner Seaman, Portland General Electric; Scott Bolton, PacifiCorp.

This September Rep. Mark Johnson, R-District 52, held an energy forum in Hood River. The panel included executives from major energy players in Oregon, but in the question and answer segment all the increasingly heated audience questions went to Varner Seamam, Portland General Electric’s State Legislative Affairs Manager and PacifiCorp’s Scott Bolton.

The big electric utilities are proposing changes to the rules that give rise to small renewable energy projects’ wind farms, solar energy systems, dairy digesters, and hydroelectric plants. The owners and developers of these projects are alarmed and angry.

Farmers Irrigation manager Jer Camarata of Hood River, Oregon told the legislators that the irrigation rates the district charges their farmers are a fourth of what they would be without the revenue from their small hydroelectric plant.

[/media-credit] Craig DeHart inspects a fish screen that replaced a dam. Allowing fish passage in the stream behind.

“We’ve spent $30 to $40 million from our funds on piping, removing fish barriers, and improving water quality–instream and for patrons,” said Craig DeHart, Middle Fork Irrigation general manager (Parkdale, Oregon). “The largest share of that has come from our hydro revenue.” Things benefiting farmers, salmon, and water conservation.

East of Wasco, Oregon, Ormand Hilderbrand developed PáTu Wind Farm on his family’s acreage. He estimates that his six-turbine wind farm puts $500,000 a year into struggling Sherman County in the form of salaries and taxes.

Others said the changes the utilities are proposing may raise irrigation rates for farmers, put some small renewable projects out of business and stop any further projects. Worst case, these changes could hamstring the energy security these independent projects are to provide.

Many of these small scale renewable energy projects came about because of a 1978 federal act known as PURPA, Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act. After the oil crisis in the 1970s the federal government decided the country’s security needed to be less dependent on imported oil and fossil fuels. PURPA was its answer. Its aim is to encourage innovative small-scale renewable energy generation. It required big utility companies like PacifiCorp and PGE to buy electricity from these small producers. While PURPA is a federal law, the individual states set the rate the utilities must pay and the length of contracts.

In Oregon, the Public Utility Commission (PUC) sets those rules. To be eligible a renewable energy project has to be generating no more than 10 megawatts?enough electricity to power about 6,000 homes–all the homes in The Dalles.

The current controversy is about the rules PUC set for the big utilities. PacifiCorp and PGE are required to buy all power generated by small projects (QFs in the bureaucratic lingo for Qualifying Facilities), offer them a 15-year standard contract, and pay for that electricity at a price the PUC sets. Generally that price is the ‘avoided cost,’ a calculation of what it would cost a utility if it had to build another energy plant.

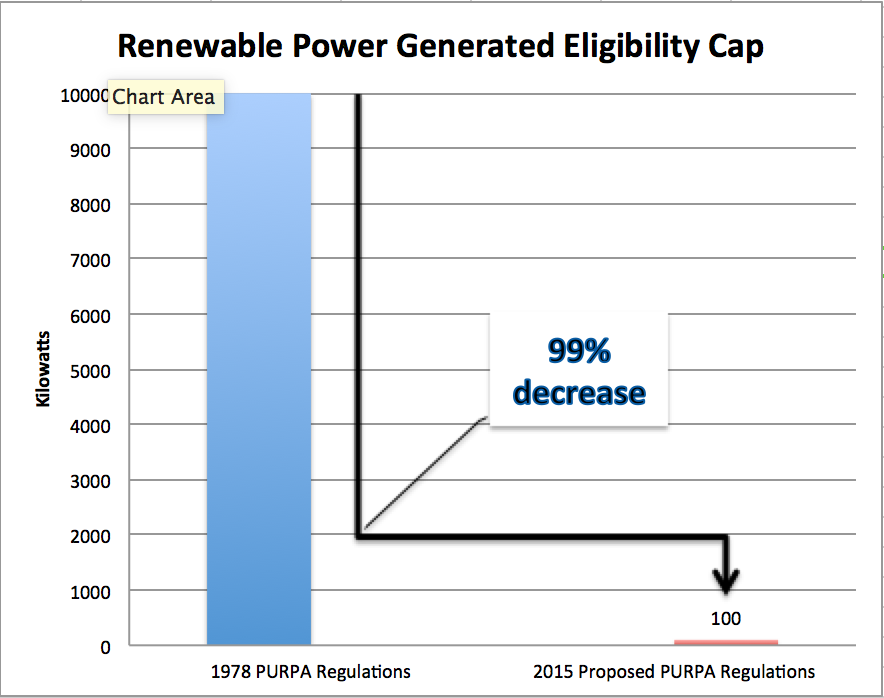

On May 21 this year, PacifiCorp filed an application with the PUC asking it to reduce the fixed-price contract length to three years and lower the eligibility cap from 10 megawatts (10,000 kilowatts) to 100 kilowatts–a 99 percent reduction.

[/media-credit] This graph depicts proposed changes of project eligibility?? compared to the current standards.

Within days, a flurry of petitions to intervene landed at the PUC, filed by both current QFs and renewable energy developers.

“At 100 kilowatts almost every qualifying facility doesn’t qualify for standard contract prices,” says John Lowe, Renewable Energy Coalition’s director, an organization representing 50 QFs (all but two are hydroelectric). “PacifiCorp’s strategy effectively stops new projects and puts existing long-term contracts into jeopardy when they come up for renewal.”

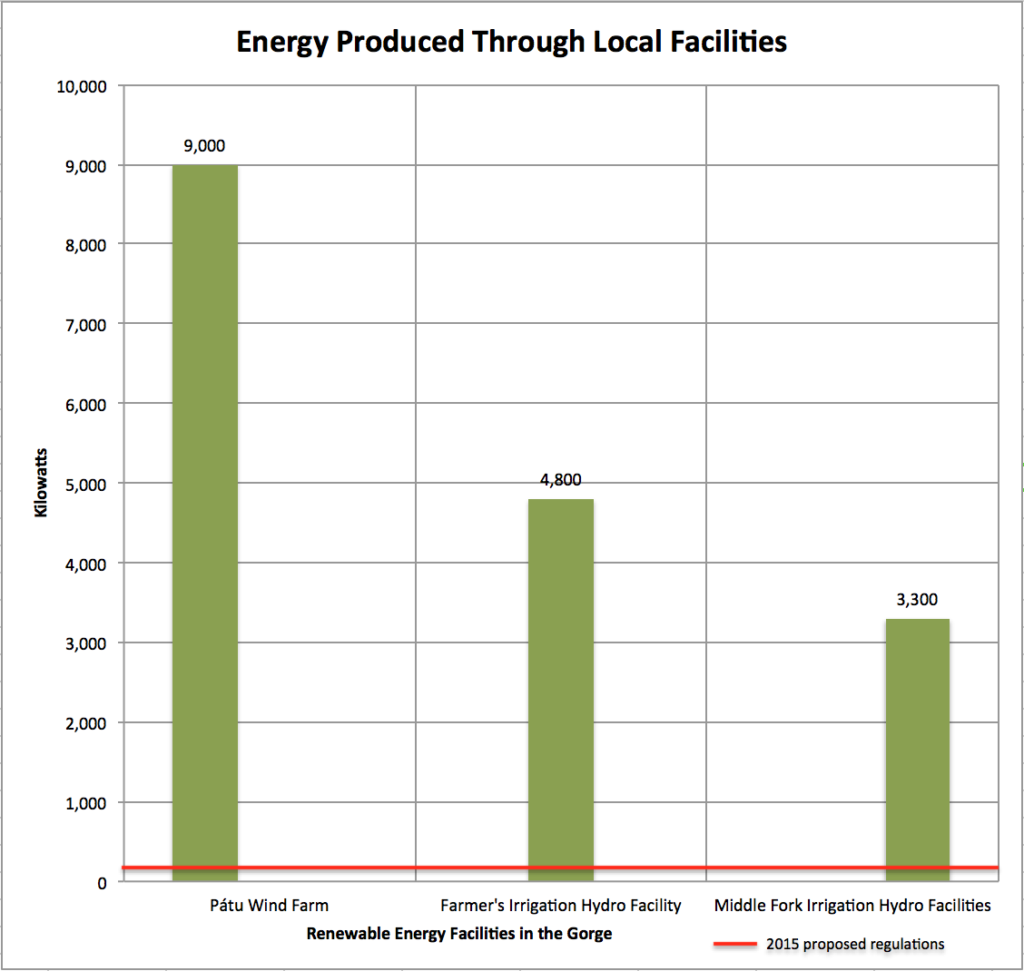

If the qualifying level is 100 kilowatts, three Gorge entities will not be eligible for the standard contract when their contracts come up for renewal. In Hood River County, Farmers Irrigation’s hydro facility generates 4,800 kilowatts (4.8 MW); Middle Fork Irrigation District 3,300. In Sherman County, PáTu Wind Farm generates 9,000.

The standard contract is important to QFs, because no time is spent on negotiating the contact term and standard published price are set.

PacifiCorp claims the increasing number of these projects is forcing them to buy more power than they need. In PacifiCorp’s filing to the PUC, they say in Oregon they are already buying 338 MW from QFs and have requests for 587 MW more. Between the existing and proposed PURPA contracts PacifiCorps stated: “would be enough to supply 56 percent of the Company’s average Oregon retail load.”

PUC staff response refutes that statistic saying that the amount would actually be less than 36 percent.

In an email to Envirogorge, Mr. Bolton, vice president of external affairs for PacifiCorp wrote, “To be clear, we are not saying ‘no’ to power purchases from renewable energy developers. We are saying that long term contracts tend to lock in prices that are not reflective of the market, which is more competitive and offering more technology choices than ever before.”

[/media-credit] A graph depicting the amount of energy a few facilities in the Gorge produce.

What has driven down the price of energy is fracking. It has provided so much natural gas that the big utilities can buy it to generate electricity much cheaper than the prices they are paying the QFs. “With natural gas prices low and the price of solar dropping, the 15 year contracts are making them and therefore their customers pay more,” Mr. Bolton says, than the current market price.

In addition PacifiCorp feels that not all the projects are coming from small producers. “The key issue here is small,” Mr. Bolton wrote. “Many of the projects being proposed are 80 MW projects backed by Wall Street firms. We don’t think these kinds of projects should be able to demand 20 year fixed term contracts with prices set 2 years ago. We think we can get our customers a better deal. Naturally, these Wall Street backed firms want to get sweetheart deals on the backs of our customers.”

Mr. Lowe agrees that some big out-of-state companies are circumventing the act’s intent. He thinks that while the system needs fixing, it “doesn’t warrant shutting down PURPA. A more surgical approach is needed.”

Once a price is agreed on, it would seem that a power source is a power source whether it’s a coal plant or a small hydroelectric system. But when PacifiCorp and PGE buy power from the QFs, the cost is passed through to the ratepayer. When they produce their own power, they can earn a return.

The three year contract is especially untenable to the QFs. “From 2008-2010, we spent several hundred thousand dollars trying to renegotiate a simple new [15 year] power sales contract,” Farmer’s Irrigation’s Jer Camarata wrote in an appeal to Oregon Sen. Chuck Thompson. “It makes no economic sense to do this every three years.” Earlier this year, PacifiCorp won a similar case to the one they are proposing in Oregon. The Idaho PUC granted their request to reduce the required contracts for wind and solar from 20 years to two years.

[/media-credit] Wind turbines in eastern Washington.

Equally troubling to the QFs is what might happen when they need to upgrade their systems. Mr. Hilderbrand estimates he went to 30 to 40 banks trying to find one willing to loan him $20 million to construct his six-tower wind facility. He fears that when he needs to upgrade, which could easily run $10 to $15 million, a three year contract will make it impossible to find a lender.

Since the audience at Rep. Johnson’s forum included other legislators, both sides of the dispute aimed comments to bolster their positions. The legislators so far have been quiet on whether they will weigh in at the PUC.

“I think it is important that we have a dialogue about how we move forward as a community, a state and a nation,” Mr. Bolton wrote Envirogorge, “balancing the needs and costs of energy with the climate and the environment.”

That dialogue may well turn on PUC’s decision due in early 2016.

The laws(PURPA) that require electric utilities to purchase energy from small independent renewable energy producers threatens the business model of the typical utility. This threat has increased with the advancements in technology, reduction in cost and increased demand for renewables. While the old model for centralized power with regulated monopolies worked well for nearly a century, the times are changing. Distributed generation with a variety of resource types is desirable for many reasons and it is time for Oregon to lead in moving toward that end.

This was a new issue for us at Envirogorge and we wanted to write about it, because we think few people know about it and how it affects them.

Thank you. It is a dry subject that few people understand. The regulated utilities are very good at thwarting small generation and have monetary resources that dwarf the less organized independent power producers. This is a difficult battle, maintaining the ability to sell home grown energy to our neighbors.

Thanks for your thorough reporting.

I called PUC yesterday and they say an abeyance motion will be decided on next week. It will be interesting to see what happens then.

Thanks so much for covering this very important issue! Great, balanced article.

–Jer Camarata, FID

Thank you very much, Jer. We here at Envirogorge try our best to give a voice to all sides of an issue and provide a wholistic story. We hope you’ll keep us updated on the Central Oregon Irrigation District!