An OSU prof says $9 billion spent on recovery of wild salmon and steelhead has had no measurable impact. So just give up then?

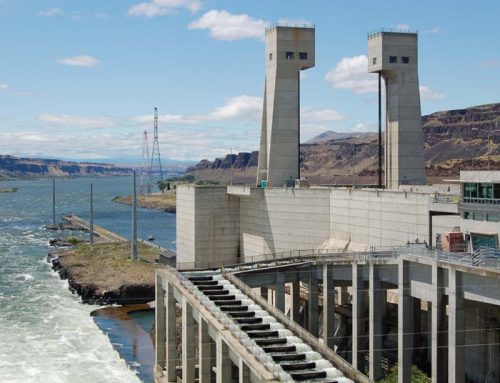

Money pit: The Elwha Dam removal and total Elwha River restoration in Washington’s Olympic Mountains cost $351 million in 2011-12. “Salmon have returned, swimming up past the old Elwha Dam site,” reported American Rivers in 2014. Photo: NOAA

By Chuck Thompson. August 2, 2023. Over the past four decades the public has invested more than $9 billion in inflation-adjusted tax dollars in an effort to conserve and improve salmon and steelhead populations in the Columbia River Basin.

Has all that money, and the endless hours of human effort associated with it, been a complete waste?

That seems to be the implication of a new study from the Oregon State University College of Agricultural Sciences titled, “Return(s) on investment: Restoration spending in the Columbia River Basin and increased abundance of salmon and steelhead.”

The study was published last week in the scientific journal PLOS ONE.

Led by William Jaeger, a professor of applied economics, the study is based on an analysis of 50 years of data “suggesting that while hatchery-reared salmon numbers have increased, there is no evidence of a net increase in wild, naturally spawning salmon and steelhead.”

An estimated 16 million salmon and steelhead once returned from the Pacific to the portions of the basin above Bonneville Dam, according to Jaeger, but by the 1970s there were fewer than 1 million fish, prompting the federal government to intervene.

There’s something you should know: William Jaeger. Photo: OSU

“The Northwest Power Act of 1980 required fish and wildlife goals to be considered in addition to power generation and other objectives. The act created the Northwest Power and Conservation Council to set up conservation programs financed by Bonneville Power Administration revenues,” according to an OSU press release. “The cost and scale of restoration efforts grew considerably in the 1990s … following the listing of 12 Columbia River runs of salmon and steelhead as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.”

The public’s $9 billion-plus tab for the collective conservation effort doesn’t take into account monies spent by local governments and non-governmental agencies.

“A key question has persisted, and its answer is critical for sound policy and legal decisions: Is there any evidence of an overall boost in wild fish abundance that can be linked to the totality of the recovery efforts?” asks Jaeger. “Based on a half-century of fish return data at Bonneville Dam, the single entry point to the basin above the dam, the evidence does not support a yes answer.”

So … no?

“We found no evidence in the data that the restoration spending is associated with a net increase in wild fish abundance,” says Jaeger.

The study also focused on fish hatchery expenditures and results.

“The role of hatcheries in recovery plans is controversial for many reasons, but results do indicate that hatchery production combined with restoration spending is associated with increases in returning adult fish,” says Jaeger. “However, we found that adult returns attributable to spending and hatchery releases combined do not exceed what we can attribute to hatcheries alone. We looked at ocean conditions and other environmental variables, hatchery releases, survival rates for hatchery released fish and conservation spending, and we saw no indication of a positive net effect for wild fish.”

Even expenditures on “durable” habitat improvements designed to cumulatively benefit naturally spawning wild salmon and steelhead over many years did not lead to evidence of a return on these investments, he added.

So what now then?

While the study says spending on fish conservation efforts haven’t amounted to much, it neither addresses the implications of its dramatic conclusions nor offers suggestions for future conservation spending strategies.

If conservation efforts haven’t produced measurable positive results, does this mean conservation efforts aimed at wild fish should be abandoned?

Should conservationists pivot to radically new strategies?

Can we assume that even if conservation efforts haven’t recovered wild stocks, they’ve at least forestalled an even larger species collapse, suggesting that conservationists stay the course (and expenditures) in the hopes that long-term impacts will begin to appear?

“The actual impact of all of these efforts has always been poorly understood,” says Jaeger. “Lots of people have long been concerned about a lack of evidence of salmon and steelhead recovery. One of the issues is that most studies evaluating restoration efforts have examined individual projects for specific species, life stages or geographic areas, which limits the ability to make broad inferences at the basin level.”

Jaeger’s study takes a broader perspective. Whether his study finds a broad audience—and what that audience will do with its conclusions—may require further research. And, of course, funding.