Gibbons Creek, which enters from the Refuge’s west side, provides important habitat for salmon, waterfowl and other native species. Photo by Jurgen Hess

By Valerie Brown. Jan. 9, 2020. Migratory birds heave a sigh of relief when they reach the Columbia River, where they can take the Steigerwald Lake exit from the Pacific Flyway. The lake is the namesake of a small body of water and a floodplain along the Columbia River just east of Camas/Washougal, Washington. Managed as part of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge Complex since 1987, the 1,049 acre Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge sits right at the western boundary of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. And this year, it will undergo a major transformation: being reconnected to the river.

A wildlife rest stop

Steigerwald’s position is unique. The Columbia River is the first break in the Cascades encountered by migratory birds using the north-south flyway along the west side of the mountains, and the only sea level east-west corridor south of the Fraser River in Canada.

“If you think in terms of highways, where they cross is where we would put a hotel, gas stations, restaurants,” says Steigerwald steward Wilson Cady. Within the Gorge there are few places for either fish or fowl to rest. Which makes Steigerwald a vacation spot, truck stop, and rest area for migratory species, as well as a permanent home for dozens of others. Many birds move back and forth through the Gorge, some intentionally, Cady says, some just taking wrong turns or getting caught up in one of those notorious east winds.

The Columbia corridor is also an important channel for the migration of salmon and lamprey, and the Bonneville Power Administration is legally required to mitigate the destruction of fish habitat caused by dams. Part of the logic behind the Steigerwald project is that restoring shallow freshwater habitat of several kinds will help juvenile salmon prepare for their trip to the sea by offering plenty of food, little to no current, and some protection from predators.

Many ducks in a row

The project entailed lining up a lot of ducks in a row. The Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership (LCEP), formed by the governors of Oregon and Washington and the Environmental Protection Agency in 1995, teamed up with the Bonneville Power Administration, Friends of the Columbia Gorge and others to jump through all the bureaucratic hoops necessary to revitalize Steigerwald. They came up with a plan, funded by the BPA and the Washington Department of Ecology, that will reconnect 965 acres with the river.

Steigerwald was separated from the Columbia 54 years ago for human purposes, including agriculture and industry. Levees were built to keep the river out. Gibbons Creek, which enters the floodplain at the refuge’s west side, was diverted and forced into an aqueduct along the top of the levee protecting the Port of Camas-Washougal Industrial Park, the Washougal Wastewater Treatment Plant and some residences. Not surprisingly, Gibbons Creek has repeatedly flooded the structures the levee was built to protect.

The diversion and channeling of the creek also eliminated the alluvial fan at its entrance to the floodplain. So any migratory fish trying to use Gibbons Creek for spawning have to negotiate the diversion, the levee aqueduct and the fish ladder to reach their goal.

Aerial view of the area to be restored. Photo courtesy of Refuge Stewards

In ecological terms, the Steigerwald project is huge. It’s the largest chunk of land on the lower Columbia available to add freshwater habitat for fish, says Dan Bell, land trust director for Friends of the Columbia Gorge, which purchased 160 acres of private land in the floodplain to add to the refuge. Steigerwald is “one of only a couple of places where you could conceive of a project like this at this scale,” says Bell.

In addition to the positives for wildlife, there will be quite a few benefits for people as well. “It’s rare,” says Debrah Marriott, LCEP’s executive director, to have “a project of this size in that particular geography with the Gorge and the metro area.” She ticks off the benefits: “Reduce flood risk, expand recreational opportunities, fix flooding on the highway, engage kids, and reduce financial impacts on the Port and USFWS for repair and maintenance.”

Long-term commitment

Generations of area residents have enjoyed birding and simply walking the trails, and no one is more familiar with the area than Cady, whose history of the Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge is replete with colorful anecdotes. He writes that after the levees cut off river access, a variety of human uses were proposed, most based on the idea that the area had no wildlife value. These included a dock and turning basin for barges. But locals, especially birders, knew very well that plenty of wildlife used the area.

The federal refuge was created in 1987 with the support of Oregon senator Mark Hatfield, who did not want sightseers at Crown Point on the Oregon side to look down at an industrial area. That was the same year the Washington legislature changed the Department of Game to the Department of Wildlife, reflecting a major shift in both public opinion and government policy from valuing undeveloped land for industry or hunting to seeing it as wildlife habitat.

Since then, conservation management principles have further evolved in the wake of plummeting salmon and lamprey populations, and resource managers have moved toward more holistic ecological and landscape-scale approaches rather than single-species perspectives.

The details

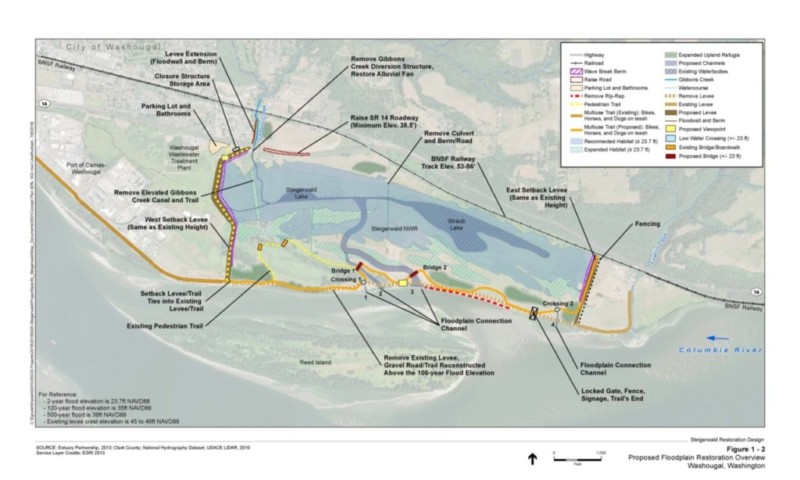

A detailed map shows how the restoration project will move forward. (Ctrl + Click to enlarge) Map courtesy of Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership

The basic restoration plan is relatively simple: undo the features that prevent the river from reaching the floodplain without worsening flood risk for infrastructure. The levee along the river will be breached at several points, while the levee protecting the industrial park and the municipal wastewater treatment plant, along with a residential area, will be rebuilt. Gibbons Creek will be allowed to debouche into the floodplain via its own new alluvial fan. Its diversion structure and fish ladder will be removed. About 1,200 feet of State Road 14 will be raised above the 500-year flood line, and a mile of trail will be added.

Species v. species

There has been some opposition to the Steigerwald project from waterfowl hunters, which illustrates the challenges of protecting species seen as competing for habitat. Albert O’Connor, a spokesman for both the Washington Waterfowl Association and Delta Waterfowl, stated in an email that “trading wildlife habitat including waterfowl for fish habitat will have adverse impacts to waterfowl and other wildlife. The benefits to salmon have not been established.”

The BPA’s final environmental assessment, however, notes that refuge managers intend to continue providing about the same acreage now devoted to grassland for geese that use the area during migration and nesting seasons. Chris Collins, principal restoration ecologist with the LCEP, says the project will create nearly 100 acres of wetland, and he expects the food base for waterfowl to be “more diverse and higher quality. We’ll certainly see greater capacity for those populations.” In any case, he added, the intent of planners is to re-create the environment that the native waterfowl species evolved in — an environment they shared with fish. And while the refuge has never been open for hunting, no decision has been made to ban it permanently, says Eric Anderson, the USFWS interim director for the refuge.

There is also evidence that habitat restoration projects for salmon are succeeding elsewhere in the Northwest, although most efforts are so recent that comprehensive results are not available. A 2016 study by the Nisqually Indian Tribe, the US Geological Survey and the USFWS found that since a dike was removed in the Nisqually delta in 2009, both salmon and waterfowl have begun to recolonize the restored habitat. And since the Marmot Dam was removed on the Sandy River in 2006, that river’s coho and steelhead numbers have increased markedly.

Weasels and widgeons and stilts, oh my!

The refuge will be mostly closed to the public until the project is finished in 2022, but after that visitors will have a chance to see a wide variety of animals and plants. Of the 300-plus species of birds found in Clark County, Cady says, 200 of them have been seen at Steigerwald. Local creatures include beaver, nutria, otter, mink, long-tailed weasel, black bear, cougar, bobcat, coyote, raptors and “a host of rodents,” Cady notes, along with many turtles. He adds that east-side birds including burrowing owls, sage thrashers, avocets and black-necked stilts have been seen at Steigerwald. The BPA assessment expects that cackling goose, Canada goose, wood duck, gadwall, American wigeon, cinnamon teal, and bufflehead will continue to visit as well.

Canada goose. Photo by Jurgen Hess

Anderson knows there’s at least one bittern in residence, and he says there are coho and steelhead in Gibbons Creek as well. He has hopes that “chum might once again show interest in the alluvial fan at Gibbons Creek. That would be a dream come true.”

Ryan Baker, wastewater manager for the Washougal treatment plant, has seen coyotes, deer, ducks, blue herons and a beaver wander in and between his treatment ponds (they don’t stay long), and is happy the project is underway. “Environment comes first. I wouldn’t be in this industry if I wasn’t willing to help the environment,” Baker says.

Among the admirers of Steigerwald, Wilson Cady is the most devoted. The descendant of an Oregon Trail wagonmaster, he is the third generation in his family to stay fiercely connected to wilderness despite the manic pace of human development in the lower Columbia region. Referring to the formation of the Clark County chapter of the Audubon Society in 1975, he says, “We were hoping we could save a remnant of the wetlands out there. This restoration is more than I ever dreamed of.”

Thank you Valerie. I’ve been drowning in bad environmental news lately and this article is a ring buoy.

Great article! Very nicely written, with a good combo of ecology and accessibility for non-ecologists.

Nice article with good news!