With recent downlisting of the Fender’s blue butterfly, the Oregon valley is earning cheers from conservationists

Comeback kid: Once thought extinct, the Fender’s blue butterfly was known only from collections made between 1929 and 1937, until it was rediscovered in 1989. Photo: Institute for Applied Ecology

By K.C. Mehaffey. April 6, 2023. Created in 1973, the Endangered Species Act will turn 50 years old in December.

If any place has cause to celebrate, it’s Oregon’s Willamette Valley, where over the past decade, two species have been taken off the endangered list, two more are proposed for delisting and many others are benefiting from work to restore prairie habitat.

The first fish species ever to be taken off the ESA list due to recovery—the Oregon chub—is from the Willamette Valley. It was removed from the list in 2015 and is now one of five fish species to recover.

In April 2021, Bradshaw’s lomatium, a plant species found mostly in the Willamette Valley, was also deemed recovered and taken off the list. It’s one of 20 flowering plants to recover.

Delisting and downlisting under the Endangered Species Act are far from common. Nationwide, 71 species have been delisted due to recovery since the act’s inception, and another 56 species have been downlisted from “endangered” to “threatened.”

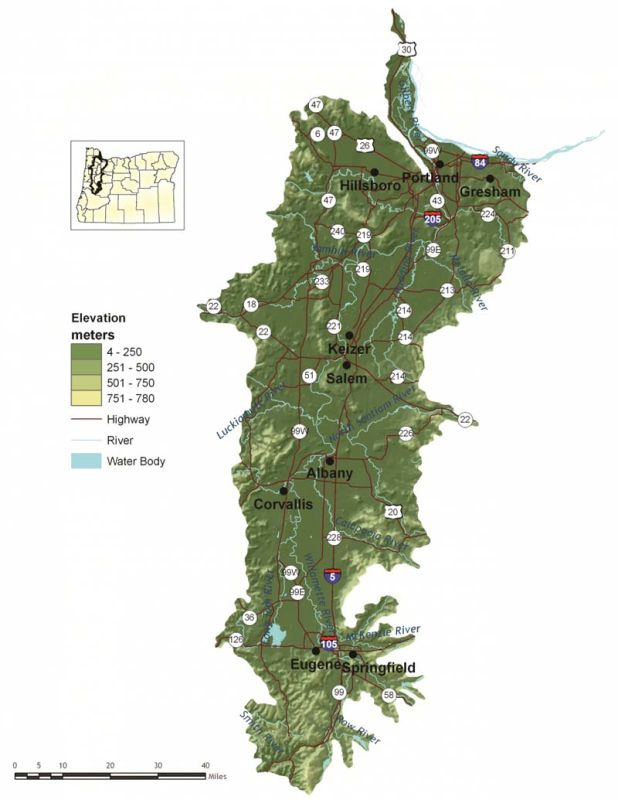

Willamette Valley. Map: Oregon Conservation Strategy/ODFW

The latest success in the Willamette Valley is the January reclassification of the Fender’s blue butterfly from endangered to threatened. Found only in the Willamette, this tiny insect with a 1-inch wingspan and a one-to-two-week adult lifespan was thought to be extinct for 50 years, until it was rediscovered in the late 1980s.

By 2000 it was listed as endangered, and 23 years later it’s rebounded enough to downlist.

In just over two decades, the population has gone from a few thousand to between 14,000 and 16,000 today.

Its host plant, Kincaid’s lupine, is also threatened. During its most recent review in 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that overall abundance appears to have increased, but the magnitude of change was not enough to propose delisting.

Like the butterfly, Bradshaw’s lomatium was thought to be extinct since the 1940s.

A graduate student discovered a few plants growing near Eugene in 1979. It was listed in 1988 with roughly 25,000 plants across its former habitat. There are now an estimated 11 million plants with enough genetic diversity to consider it recovered.

Golden paintbrush and Nelson’s checker-mallow—two more plants found in the Willamette Valley—have been proposed for delisting in the past two years.

Critical partners

As the lead agency charged with implementing the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says successes in the Willamette Valley are largely the result of a concerted effort to restore the area’s unique prairie habitats, and the help they’ve gotten through partnerships.

Restoring land in the 150-mile-long valley isn’t easy. Approximately 70% of Oregon’s population lives in the Willamette Valley, which encompasses its five largest cities. More than 95% of the land is privately owned.

“This is about all the partnerships it takes to do recovery—that’s a very big component,” says Jeff Dillon, endangered species division manager for the USFWS in Portland. “The Fish and Wildlife Service can’t do this by ourselves. We have to have partners.”

Dillon cites several state and federal agencies, nonprofit organizations and private landowners that have played a role in the prairie’s recovery.

“All these people came together and worked on the conservation and partnership and this is what we get—species that we can say, ‘Yeah, they’re doing fine now. We can step back and watch what we’ve done,’” he says. “I think it’s a huge success.”

Too soon?

But recent delisting proposals aren’t supported by everyone.

Tom Kaye, executive director of the Institute of Applied Ecology—which has worked closely with the USFWS to restore these plants and the prairie habitat they occupy—acknowledges the successful habitat work. It has included efforts by his organization to rebuild plant populations by growing them agriculturally and then replanting seeds or plugs in the wild.

But Kay says he doesn’t understand the rush to delist some plants.

He says it’s probably appropriate to take Nelson’s checker-mallow off the list, but he’s not so sure about golden paintbrush.

“I, too, want to celebrate these victories, but looking over our shoulder is a big question mark,” says Kaye.

Depth of field: Tom Kaye specializes in habitat restoration, invasive species control, endangered species reintroduction, population dynamics of plants and conservation planning. Photo: Institute of Applied Ecology

That big question mark is the impact climate change will have on recently delisted species, and the unique prairie habitat they occupy.

“I’m concerned that we’re acting too fast to delist and downlist these species when the future of the whole is in jeopardy,” says Kaye.

Dillon says climate change is taken into account when the USFWS makes an official proposal that a species has recovered enough to take it off the endangered species list.

“Anything that could be a stressor on the species is looked at, all across the gamut,” he says. “Climate change is the big new one in the mix these days. But development, disease, invasive species, loss of habitat—all that’s looked at.”

The proposal to delist plants is based on the best science on where the species is, where it’s going and whether it needs to be listed to protect it, he says.

“It’s not a simple thing to do. It’s a very complex thing. It takes a lot of resources, and it takes a lot of time,” says Dillon.

Fender’s blue butterfly

The successes are, of course, related.

Some, like the Fender’s blue butterfly and Kincaid’s lupine, are closely tied to each other.

The lupine is the butterfly’s host plant, and so recovery of one automatically aids in the recovery of the other.

But the loss of prairie habitat that caused their demise is also at the root of the decline for dozens of other species in the Willamette Valley.

Restoring both wetland and upland prairie habitat by mowing, controlling invasive species and bringing fire back to the landscape is benefiting a whole host of species—both rare and common.

Butterfly base: Kincaid’s lupine. Photo: T. Thomas/USFWS

The Willamette Valley has some three dozen species—mostly plants—that are federally listed as endangered, threatened or a species of concern.

Why so many?

With its natural prairies that were kept clear of woody vegetation by Native Americans, the Willamette Valley underwent a significant and drastic change when Euro-American settlers moved west. They arrived to find a valley filled with lush habitat and ready to convert to agriculture.

Dillon says Native Americans who lived there—called the Kalapuya—regularly burned the land to aid production of natural foods.

A history of the valley published by the University of Oregon confirms this.

The influx of settlers first resulted in the loss of the prairie grasslands, where 90% of settlement occurred prior to 1850.

In the following decades, riparian bottomlands were also cleared and drained for agriculture.

Loss and preservation

Preservation of what was left of the wetland habitat began even before the Endangered Species Act became law.

In 1964, an earthquake in Alaska caused the population of dusky Canada geese to plummet. The Willamette Valley was one of their only wintering areas. And so three national wildlife refuges totaling nearly 11,000 acres were established to ensure the geese had somewhere to go.

Dusky Canada geese aren’t listed under the ESA, but the habitat preserved for them also preserved some of the Willamette Valley’s wetland habitat.

Willamette win: Female Fender’s blue butterfly. Photo: Jeff Dillon/USFWS

In addition to the national wildlife reserves, other federal, state and municipal agencies have set aside lands for preservation.

As mitigation for federal hydroelectric dams in the valley, the Bonneville Power Administration is purchasing property and conservation easements with the goal of protecting nearly 17,000 acres by 2025.

“The major loss of wetland and native prairie are due to a number of factors, but largely just human settlement and fire suppression,” says Dillon.

In the last 15 to 20 years, he says, there’s been a concerted effort to restore and conserve prairie habitat in the Willamette Valley.

The treatment has involved mowing, prescribed fire, agricultural production of seeds and plants instead of relying on the collection of wild seeds, and working with landowners to secure safe harbor agreements.

Much of the work involves partnerships with both public and private landowners.

Kaye’s Institute of Applied Ecology is among those partnerships.

The Institute’s part in this success story is the result of putting conservation science and practice together to make real progress, says Kaye.

“We learn as we go, and test it and implement it and it works,” he says.

Measuring ESA success

Endangered species recovery work is just one of the Institute of Applied Ecology’s areas of interest.

Understanding if populations are viable in the long run is a continuing point of discussion and, in some cases, disagreement, says Kaye.

“In some cases, it really does seem to be working well. Nelson’s checker-mallow seems to be a good example. Others, like golden paintbrush—we brought that back from zero. It was entirely extinct [in the Willamette Valley]. Now, we have over 20 populations and some are very large,” he says.

But there’s evidence that some populations get big really fast and then decline.

“While on the one hand it’s really a fabulous success story, on the other hand we don’t know if we’re at the end of that story,” says Kaye. “It’s just amazing what we’ve been able to accomplish. And on the other hand, all of that is threatened by climate change.”

Power plant: Bradshaws lomatium is also called Bradshaw’s desert parsley. Photo: Peter Pearsall/USFWS

Because the Willamette Valley is the urban center of Oregon, there’s still a lot of development pressure, he says. And because of the uncertainties of climate change, the entire ecosystem where the plants and butterflies are being restored is at risk.

“It’s changing now, and it’s already changed because of climate change,” he says. “It’s going to keep changing, and it’s going to change a lot, and that’s not something we should ignore.”

As the Endangered Species Act turns 50 years old, some, like Kaye, say the mechanisms in place for delisting need to be re-evaluated given some of the likely impacts of climate change.

To Dillon, there’s a lot to celebrate.

Since it was enacted, more than 1,660 species have been listed as either threatened or endangered nationwide. Ninety-nine percent of them are still around.

“There are people out there that measure the success by how many we delisted or downlisted,” says Dillon. “I think the 99% is the biggest factor—all those species did not go extinct. So that’s a success as well.”