Even so, the state’s overall wolf population increased in 2023, fueling a debate on removing ‘endangered’ status

Recovery road: Wolves in Washington are thriving in some areas, faring worse in others. This wolf is from the Teanaway Pack, which was confirmed in 2011. In 2023, just one Teanaway wolf remained. File photo: WDFW

By Chuck Thompson. April 25, 2024. In February, Columbia Insight reported that a female wolf—half of the two-wolf Big Muddy Pack in southwest Washington—had mysteriously disappeared.

In April 2023, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife had confirmed the new pack’s existence, the first southwest Washington pack in a century. (Two wolves are enough to meet the agency’s minimum requirement to be recognized as a pack: two or more wolves traveling together in winter.)

That female wolf—the presumed mate of a collared male known as WA109M—remains missing.

In its Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2023 Annual Report, released last week, WDFW confirmed that the area no longer has a pack, much less a breeding pack.

“Although the first pack to recolonize the South Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region only had one wolf during the year end counts in 2023, we have observed multiple collared wolves south of Interstate 90 in the last year,” said WDFW Director Kelly Susewind. “This likely means it is only a matter of time before new packs begin to establish in that recovery region.”

WDFW didn’t wipe Big Muddy off the map altogether. Its area is now labeled as a “single wolf territory” rather than a wolf pack territory.

Downlisting decision

Wolf populations are increasing statewide.

In a press release accompanying its annual report, WDFW said the state’s wolf population grew for the fifteenth consecutive year.

“The report shows a 20% increase in wolf population growth from the previous count in 2022,” according to WDFW. “As of Dec. 31, 2023, WDFW and partnering tribes counted 260 wolves in 42 packs in Washington. Twenty-five of the packs were successful breeding pairs that raised at least two pups through the end of the calendar year. These numbers follow the previous year’s count of 216 wolves in 37 packs and 26 breeding pairs.”

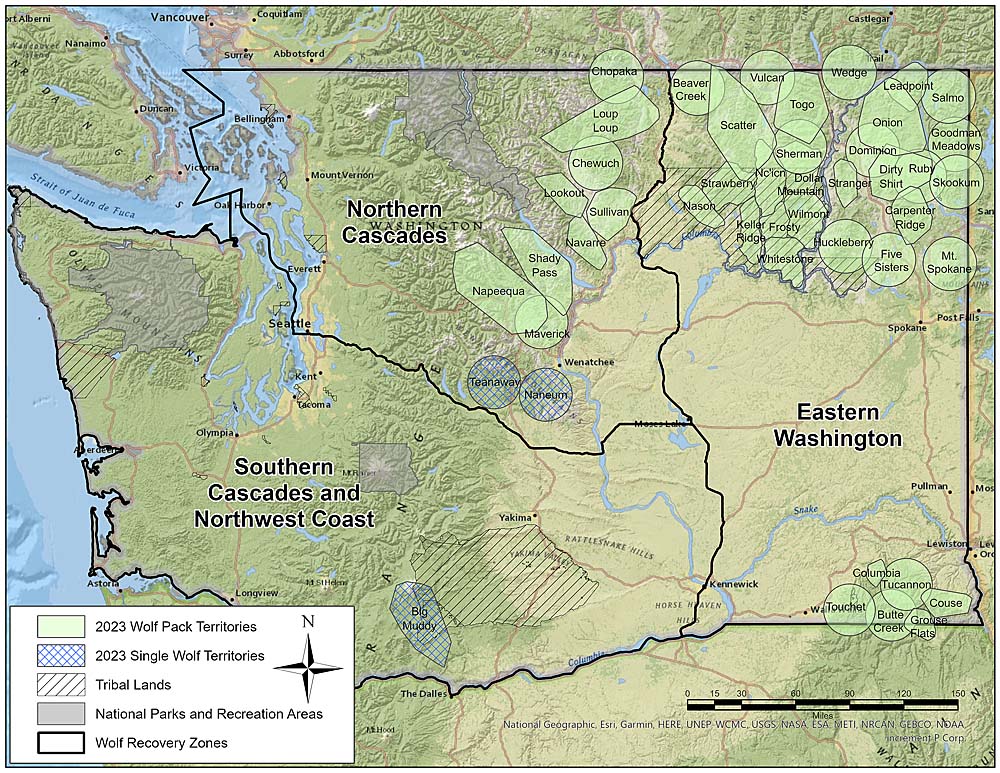

Washington wolf pack distribution in 2023. Map: WDFW

Pack sizes range from two to 11 wolves. Most packs contain four to six individuals.

Three areas contain just one wolf maintaining a territory—the former Teanaway Pack area, the former Naneum pack area and the former Big Muddy pack area.

In July, the WDFW Commission is expected to decide on a proposal to downlist wolves from endangered to sensitive, “based on significant progress toward recovery objectives.”

WDFW, however, has changed the goalposts on recovery, because one of its original recovery objectives was to have two breeding packs in the Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast region.

We need to protect our fellow Kin. We have to be the voice for them and see that they need more land to roam.

We are losing more wolves, we have to fully protect wolves. They have rights to be protected and not be killed.

In a recent winter past, while tucking in for bed, a sound permeated the night. As soon as it touched my ears – though I had never heard it before in my life – I knew deep in my bones exactly what I was hearing. My heart skipped a beat, and my beloved and I desperately stilled our softest breath, as we presented ourselves to receive this ephemeral gift…a song filled the woods that surrounded our home, and I felt it resonate in my warm and wild heart. Silence followed, and I have hung on to that song ever since. My prayer that night, and every night since, has been for all of us to coexist.

The Washington Gray Wolf Conservation and Management 2023 Annual Report is flawed. It was a cooperative effort by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Spokane Tribe of Indians, Yakama Nation, Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Tribal hunting is the largest source of wolf mortality in Washington.

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation have a year-round wolf hunting season with no daily or yearly “bag” limits, as well as a four-month wolf trapping season. The nearby Spokane tribe has also legalized wolf hunting.