Wash. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers’ decision to retire from Congress leaves a power void in the long-running dams fight

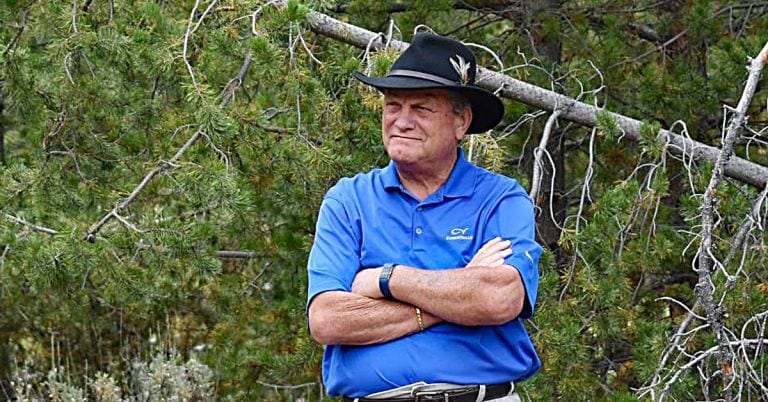

New opening: Wash. Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers has stood in the way of dam removal. Will her successor? Photo: Gage Skidmore/Wikimedia Commons

By Kendra Chamberlain. February 20, 2024. For the past two years, the chair of the U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce has come from the Pacific Northwest.

That’s significant because the committee has a broad jurisdiction encompassing energy, the environment and more. This includes approving legislation before any action could be taken to breach or remove four contested dams along the Lower Snake River.

But earlier this month, Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.) announced she won’t run for reelection this year. (Ore. Republican Greg Walden has previously served as the committee’s chair or ranking minority member.)

Vice Chair Kelly Armstrong (R-N.D.) is also leaving the House to run for governor of his home state.

This leaves leadership for the committee—which will play a key role in the future of the dams that many enviros want to see breached—up in the air.

The Hill reports two Republicans are vying for the top spot: Brett Guthrie (R-Ky.) and Bob Latta (R-Ohio).

If the Democrats win back the House in November, Frank Pallone (D-N.J.) could become the chair as the committee’s ranking Democrat.

The only remaining committee member from the Pacific Northwest is Rep. Kim Schrier (D-Wash.), who is also the minority’s vice ranking member.

Schrier’s role in the dams drama could become particularly important if the Democrats win back the House in 2024.

So where does she stand on the dams? Hard to say.

In 2022, Schrier sent a letter to President Biden expressing her “disappointment” over the release of draft reports related to the dams. [A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Schirier’s 8th Congressional District includes all four of the contested Snake River dams. In fact, it contains none of the dams. —Editor]

“I continue to support policies that are grounded in the best available science, honor tribal treaty rights and reflect the cultural and economic values of our region,” she wrote in 2022. “Washingtonians know that the question of the four Lower Snake River Dams is a complex one and that it’s a decision that should be made in consultation with all affected stakeholders, not by an agency in Washington, DC, 3,000 miles away.”

Last month, Schrier struck a similarly cautious tone.

“I’ve long said that the issue of the Lower Snake River dams is incredibly complex,” she said. “And because of that, all constituents who have a stake need to have a seat at the table.”

Repubs still saying no

Any dam breaching would require congressional authorization and likely need to get past the Energy and Commerce committee before being approved.

McMorris Rodgers has fiercely opposed the idea of breaching the dams, arguing that to do so would jeopardize grid reliability in the region and “permanently harm our way of life in Washington.”

Republicans generally opposed potential breaching of the dams during the handful of congressional hearings held on the subject last year.

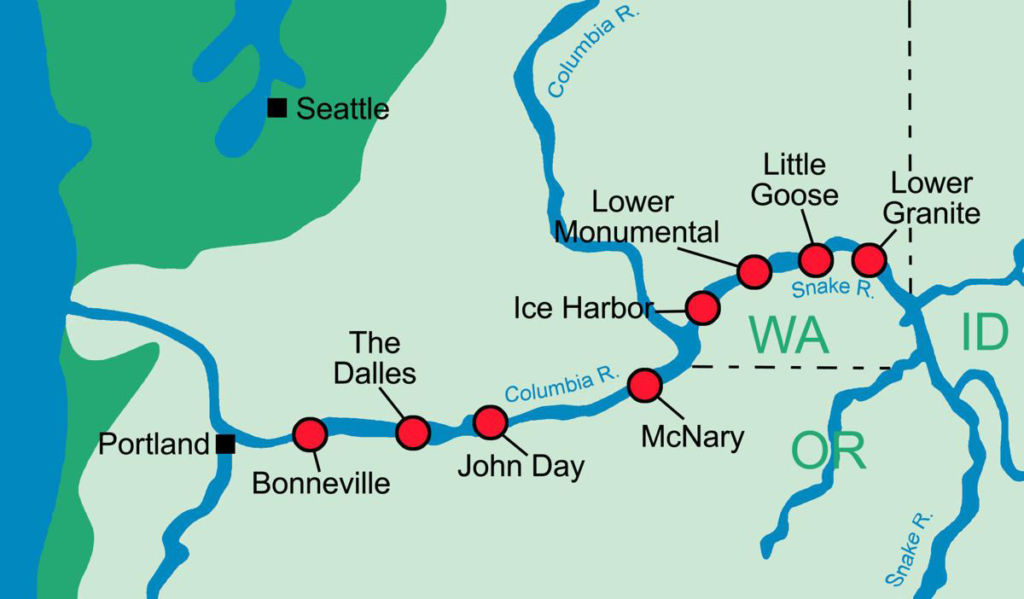

Fish fight: Conservationists have long fought to restore the Snake River watershed by having Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite dams breached. Map: USACE

But Greg Reynolds, Snake River campaign director at the conservation nonprofit Trout Unlimited, points out that the first person to bring the idea to Congress was Idaho Republican Rep. Mike Simpson.

“He brought it forth with the idea that we need a bipartisan solution that works for everybody in the region,” McReynolds told Columbia Insight. “The issue remains bipartisan, and the solution has to be bipartisan. That is how we get this done, by looking forward to what the region needs.

“My hope is that the next chair will be focused on looking forward and not looking back, so that we can move the region forward to a future that has salmon and abundant energy, as opposed to where we are now, where we don’t have an abundance of either.”

The presidential election will grab headlines, but, as usual, it’s the down-ticket races that will determine how environmental actions on the ground are legislated.

Or not.