[/media-credit] Eileen Wali and dog Lola admire recently planted trees at Sandy River Delta.

By Susanne Wright. Nov. 28, 2016. The Sandy River Delta, an ancient Mt. Hood mud flow, marks the dividing line between the Columbia River Gorge and urban Portland. It’s easy for motorists to speed past this place, unaware of its existence. But to ignore it is to miss out on its treasures and its tale of survival.

In November 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition explored the delta giving the first written description. They recorded in their journals an extraordinary landscape so thickly forested they could not walk through it.

Fertile forests and wetlands supported deer, elk, bobcat, sea otters, and so many birds and waterfowl the explorers complained: “I could not sleep at night…they were emencely (sic) numerous and their noise horrid.” (Lewis and Clark Journals, Nov. 1805)

What the travelers encountered was an active floodplain, the result of progressive sedimentary deposits from Mt. Hood that formed and sustained the delta throughout its geologic history. Long before Lewis and Clark’s arrival, Chinookan Indians thrived along the Columbia River here, fished the delta’s shores, and hunted in its forests and grasslands.

The area the Chinook knew and Lewis and Clark encountered was a unique wild river delta alive with riparian complexity and wildlife. Yet, in a mere 130 years, humans would alter forever what nature had taken a millennium to create.

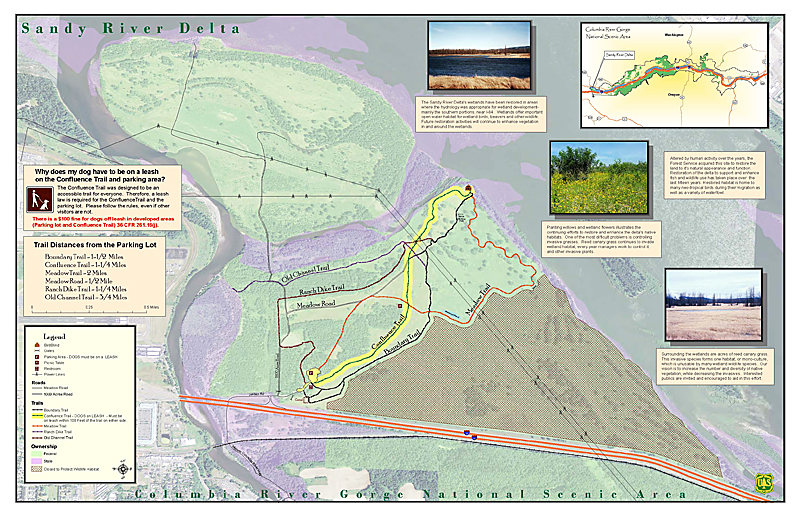

Hiking map of Sandy River Delta to download and see in detail click here

Hiking map of Sandy River Delta to download and see in detail click here

First a railroad and then a highway cut across the delta, obstructing deer and other wildlife. But most scarring was the 1932 erection of a dam across the main channel of the Sandy River, erected in a disastrous attempt to improve declining smelt runs. The exact reason for the decrease was, and is still, unknown. Scientists think factors such as dams, unregulated fishing, and river pollution all played a part. Biologists thought the solution lay in building a 750 foot dam across the Sandy River’s east channel to force it into its shorter west channel.

“Well, of course it didn’t work,” says Robin Dobson, Ecologist, U.S. Forest Service, Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The dam robbed the delta of its natural hydrological complexity. The once healthy east fork teeming with smelt gradually became little more than a slough, causing smelt stranding and death.

Sandy River Delta November 2016

After that, only the delta’s forests remained untouched, and yet, even they were eventually destroyed. On May 30, 1948 the Vanport Flood surged across the delta wiping out its woodlands. “In 1948 everything changes with the Vanport flood,” says Dobson. “It ran right through the delta. The trees, forests, everything was gone.”

Enticed by this expanse of newly opened land, Paul and Verla Martin purchased the ravaged delta in the late 1940s and began planting crops and grazing cattle. In the early 1950s they fell ill, their cattle died and their crops poisoned.

Reynolds Metals Company, located a quarter mile west, operated an aluminum plant for the war effort. Its production methods caused huge quantities of fluoride to escape, settling on the Martin’s farm, absorbing into vegetation and contaminating their water. Upwards of 3,281 pounds of fluoride were emitted daily, showering a four mile radius with toxic chemicals, sickening the Martins and killing their cows. They successfully sued Reynolds Metals Company for damages, but were forced to move away from their delta farm to avoid further contamination.

A dam, rail line, highway, historic flood, cattle grazing, and chemical contamination. It would seem the once resplendent Sandy River Delta had been leveled to its very bedrock, its natural resources mined to extinction, yet there was more potential degradation to come. In 1950 Reynolds Metal Company installed a fume chemical control system; and cattle grazing on the delta resumed. “By 1992,” says Dobson, “it had 300-600 head of cattle and was so heavily grazed it had a foot of dust in the summer months.”

Investors saw another potential for this land, eying its location on Portland’s fringe for commercial development. Nathan Baker, Staff Attorney, Friends of the Columbia River Gorge, writes in their fall 2002 newsletter, “Plans for golf courses, industrial development, truck-weighing facilities, and housing developments were announced…”

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

It appeared the delta’s legacy as a regional treasure was to be sacrificed for commerce. But in true cinematic fashion, just as the heroine is about to meet her doom, she has a stroke of good luck. Trust for Public Lands, a non-profit organization that funds the creation of parks and protected lands, swooped in and purchased the delta from Reynolds Aluminum Company for $2.76 million in 1988, “…enabling it to be forever preserved as Oregon’s gateway to the Gorge.” (Nathan Baker, Fall 2002 Newsletter) What it meant for the Sandy River Delta was protection and public access.

The Trust for Public Lands planned to place the delta with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to create a sister refuge to Steigerwald Refuge, which lies across the Columbia River in Washington. But the USFWS didn’t have sufficient funds for the purchase. The U.S Forest Service, Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, newly flush with land acquisition funding, bought it in 1991.

Because of the delta’s riparian habitat and outstanding scenic values, “It was regarded as a high priority for U.S. Forest Service acquisition to ensure its protection,” says Dobson.

Despite the Forest Service’s mission to protect the delta, it was quickly apparent they had purchased a land with many problems: abused, neglected, and supporting a few hundred hungry cows. But the land quickly drew a wide variety of users: joggers, bird watchers, hunters and the level of interest in its restoration was high.

[/media-credit] Columbia Riverkeeper and Project YESS working on restoration at Sandy River Delta Nov. 10, 2016. “The hardworking crews have planted thousands of native trees, removed acres of invasive plants, improved salmon habitat, and protected critical wetlands” in the Columbia River Gorge.

Working with various agencies and the public, the Forest Service created a comprehensive low-impact, sustainable plan, which included developing a trail system for visitors and restoring its forests and wildlife habitat.

Many volunteer groups, coordinated by the Friends of the Trees, turned out to plant hundreds of trees, but this effort stalled when the Friends of the Columbia River Gorge threatened the Forest Service with a lawsuit for “bypassing the public and disregarding environmental laws in allowing the grazing of 120 cattle and construction of cattle fencing.” (Nathan Baker, Fall 2002 Newsletter). The Forest Service halted the grazing, but that led to an explosion of non-native plants fanning out across the delta.

“Since the cattle came off two years ago, a rogue’s gallery of non-native plants has overrun the delta. Bull thistle, tansy ragwort and reed canary grass have thrived. Blackberries have exploded. Without intervention, the Forest Service might as well rename the delta the Himalayan Blackberry National Monument.” (The Oregonian)

This unexpected turn of events showcased the severity of the delta’s broken ecosystem. It was clear that correcting it would require a massive effort. The Forest Service weighed its options and initiated an aggressive approach with funding from Ash Creek Forest Management and Bonneville Power Administration. “We decided to go all out with machines. We had to,” says Dobson. “So out came tractors to pull down the blackberries. We went into it big time. And then we put out rows of trees. It was complicated. We did a lot.”

[/media-credit] Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership volunteer tree planting event Nov. 19, 2016 at the Thousand Acres site. Another is planned for Dec 10 this year.

The forests now once again are flourishing thanks to concentrated reforestation efforts and funding from the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers and Ducks Unlimited, and work by Friends of Trees, Sandy River Basin Watershed Council, Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership, Columbia Land Trust, Columbia Riverkeeper, Project Yess, and others.

“You walk through the delta in 2016 and it looks like a regular forest,” says Dobson. “Back are black cottonwood, Oregon ash, snowberry, Indian plum, and dogwood. We are hoping things get bigger and bigger.” The maturing forests, it’s hoped, will provide wildlife habitat including bringing back the Yellow-billed Cuckoo, that has not been seen on the delta for decades. Three years ago, to the delight of birders, one was spotted near the delta’s Bird Blind. “It’s an indication we’re on the right track,” says Dobson.

In 2014, the Sandy River Dam was removed. The last section to be restored is a swath of open land bordering Interstate 84. A geological survey revealed that the area once contained numerous watery sloughs and wetlands supporting the mighty numbers of waterfowl Lewis and Clark reported. Drained decades ago to make pasture for cattle, the area is heavily infested with reed canary grass. The Forest Service plans to recover these crucial wetland habitats; they are currently pursuing funds to begin a large scale restoration.

A full parking lot at the Sandy River Delta

Located on Portland’s urban edge, the delta’s visitor trails have become a popular destination for hikers, runners, birders, equestrians, and dog walkers.

Lots and lots of dog walkers. With dogs comes dog poop.

The Friends of the Sandy River Delta, a non-profit, volunteer organization that maintains trails and cleans up the site estimates it removes roughly 450 pounds of dog waste and trash from the delta each week.

“The delta is remarkably clean considering its heavy use, but many still don’t recognize that access to the delta is a privilege gained from the hard work of a few committed individuals,” says FSRD liaison Jeff Schuh. “The delta is not a dog park and dog walkers need to recognize this. There is concern the delta may become a victim of its own success. We hope that all visitors understand the need to be responsible.”

Dog waste receptacles

Since Lewis and Clark stepped foot on the delta 211 autumns have past. The Sandy River Delta of today more closely resembles the extraordinary forest habitat the explorers encountered than at any other time. It’s a gateway to the splendors of the Columbia River Gorge, a wild place discovered and squandered and ultimately redeemed; a movie drama worthy of an Oscar.

Key Youra and her dog Rocket often walk the delta’s paths. “I like the beauty, birds, birdsongs, and the sky. It’s close to town, yet a world away.”

Friends of the Sandy River Delta volunteers working on the boundary trail.

We had some questions about the specifics about the dog waste on facebook. This is an email response from Friends of the Sandy River Delta about dog waste and how it is handled by their volunteers:

Regarding dog waste, When we first began discussing the Delta with the Forest Service around 2005, we were told that they were investigating composting disposals for the dog waste. That proved unfeasible, and we continued to discuss options.

At the same time, we began monthly clean-up sweeps of the trails, especially the first few hundred yards. We would also enlist visitors to help by taking a garbage bag on their own. This was in general effective in establishing some level of self management by what was at the time, relatively low numbers of visitors.

We continued to discuss waste management, and although the Forest Service preferred a “pack it in – pack it out” approach, we suggested that this would be difficult to manage and enforce.

We suggested they allow us to place cans out in the field that we would manage (haul waste out and replace liners). We began to do this weekly, and for a time would haul the bags ourselves to a disposal site, but the Forest Service quickly took the responsibility of retrieving the bags, and disposing.

Soon we all realized that it would be worth the expense of having a trash hauler provide a dumpster. Currently, our volunteers go through the site once/week to haul the contents of estimated 16+ cans to a dedicated dumpster in the parking lot (behind an enclosure and locked to discourage dumping). During the summer, we sometimes empty the cans twice/week.

Though there are always those who don’t comply due to distraction, or neglect, most users understand the need to keep the area clean, and we likely collect well over 95% of the dog waste. Also, many regular visitors will take the responsibility to pick up after other users.

I hope this helps.

Jeff