A recent report shows an explosion of growth of a non-native species in the Columbia River. What does that mean for salmon and the cultures built on them?

Growing issue: Juvenile shad are becoming more common in the Columbia River Basin. Photo: James Ervin

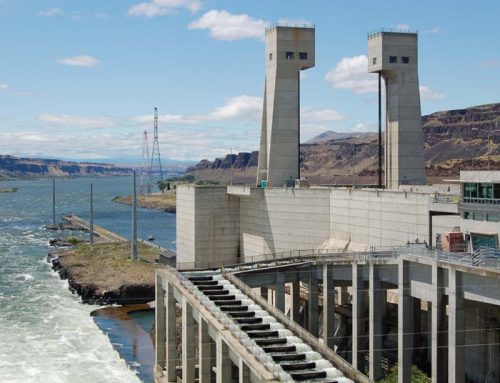

By Eli Francovich. January 27, 2022. In 1957, the steel gates of the Dalles Dam closed and—13 miles upstream on the Columbia River—one of North America’s largest waterfalls was inundated with water.

With that, an important Indigenous cultural gathering place was flooded and an unforeseen ecological cascade triggered.

Now, 77 years later, often the most common fish found flopping up Bonneville Dam’s fish ladders are nonnative shad, a silvery member of the herring family and the unlikely beneficiary of the flooding of Celilo Falls.

“The shad are, even though they run out to the ocean and come back, they are not great swimmers like salmon are,” says John Epifanio, lead author of a newly published report examining the proliferation of shad in the Columbia River system.

Some years shad, which were introduced to the West Coast in the 1880s, make up more than 90% of recorded upstream migrants, according to an Independent Scientific Advisory Board report to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council published in November.

Not-so-secret spot: In June and July anglers line up below Bonneville Dam to catch some of the millions of shad migrating upstream. Photo: Rob Phillips

What impact these fish are having on native ocean-going species like salmon and steelhead still isn’t clear.

While the report doesn’t offer any definitive answers, it does show how ecological disruptions, whether from hydroelectric development or climate change, can hurt one species while benefiting another.

The horseshoe-shaped Celilo Falls is a prime example.

The falls once dropped 40 feet. Migrating steelhead and salmon battled up and over the falls during their yearly migration.

But, for the nonnative shad the falls proved to be an unnavigable obstacle.

Now that the falls are submerged that’s no longer the case.

‘We’re salmon people, not shad people’

Prior to 1960, there were fewer than 20,000 adult shad per year at Bonneville Dam, which is downstream of Celilo Falls.

After the Dalles Dam was built that number rose to 1 million a year, and shad numbers have increased on average 5 percent each year.

That means the shad population is nearly doubling every decade, says Epifanio.

Dams of the Columbia River Basin. Map: USACE

In addition to the removal of the physical barrier, the hydroelectric system has also slowed the downstream flow of water, which has raised overall water temperature. It’s possible shad, which can survive a wider range of temperatures than salmon, have capitalized on that fact, too.

“There have been a lot of changes. It just seems to have favored these guys and they’ve taken advantage,” says Epifanio.

MORE: Thermal hopscotch: How Columbia River salmon are adapting to climate change

Regardless of the cause, shad numbers have increased.

What’s more, they’re making it farther upstream and into the Snake River above Lower Granite Dam, says Jay Hesse, director of biological services for the Nez Perce Tribe’s Department of Fisheries Resources Management. The tribe was not involved in the study.

“Their abundance is increasing to really notable levels,” he says. “And their distribution at those higher levels is also expanding.”

That’s concerned Nez Perce biologists who worry shad may hurt their already struggling steelhead and salmon populations.

Overwhelming: Amid lots of shad, one chinook salmon (bottom, center) passes through the Bradford Island Fish Ladder & Count Station at Bonneville Dam. Photo: USACE

The report doesn’t establish any direct link between the shad increase and the salmon and steelhead decrease, however it does offer a few theories on how shad may negatively impact salmon.

For example, higher-than-normal shad numbers may be supporting a larger avian predator population and shad may be competing for food sources and nursery habitat.

Learn more about your environment: Subscriptions to Columbia Insight are free.

Such a large-scale change in the Columbia Basin’s migratory fish population is alarming ecologically.

And for people and cultures that venerate salmon, steelhead and lamprey, it also highlights the loss of a way of life, says Anthony Capetillo, aquatic invasive species biologist for the Nez Perce tribe.

“We’re a salmon people, not a shad people,” he says.

What’s the problem?

It couldn’t be more different on the East Coast where shad are a valuable and sought-after sport and commercial fish.

Although bonier and oilier than salmon, shad are tasty. Ironically, shad populations on the East Coast are in decline.

Developing a commercial and recreational fishery in the West may be one way managers can control the proliferation of shad, says Stuart Ellis, harvest management biologist for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission.

While still not a popular species for anglers, shad fishing has grown in popularity in recent years.

https://youtu.be/GzNLgZJydDE

“It’s a huge amount of protein. Perfectly good protein,” Ellis says. “There is no reason not to catch these fish—we don’t need them in the system.”

The Wild Fish Conservancy is also examining experimental trapping methods that could trap shad while not accidentally trapping salmon, steelhead or other unintended species.

Epifanio and other researchers involved in the study hope their report prompts further investigation, particularly into how, or if, shad are hurting native species.

Study subject: Fat content of American shad being measured using a “fatmeter.” Photo: USGS

“At the very least, we just need to continue to monitor what these populations are doing in the basin,” he says. “We hope that we don’t just monitor. We want to have some solutions.”

READ MORE INDIGENOUS ISSUES STORIES.

The Collins Foundation is a supporter of Columbia Insight’s Indigenous Issues series.

Thanks for the article Eli. We have been raising this issue for some time now. It is hard to measure the impact of Shad because the impact is indirect. They don’t eat the out-migrating smolt, but they are occupying the same habitat. A shad produces hundreds of thousands of eggs, a salmon 2000-6000. So the shad are feeding more than the birds referenced in the article, they are feeding the other non-native fish species now in the river which are predators for out-migrating salmonid. Further, there is evidence that the salmon will delay their migration at a ladder when it is filled with live and dying shad. With climate change, delayed migration increases mortalities. There is a solution and the issue can be put to bed in just a few years. The solution is to put in an automated sorting system in every fishway on the Bonneville dam, so the shad can be sorted out of the Columbia River at the very first dam. Within two years, the shad lifecycle, the number of shad in the river would be nearly eliminated. We have such a system, It is part of our Whooshh Passage Portal for selective fish passage that we developed for a better fish passage. We call the subsystem Fishl Recognition ( a play on the common Facial Recognition technology) but the principles are pretty similar. When our cameras see a shad as they pass under our scanner, the computer activates a gate and we can sort it out of the fishway, and the river, so it never has a chance to make it past the first dam and spawn. We are currently working on two shad projects on the East Coast where American Shad are native and passage at dams is desired. Reducing delays in the upstream migration of salmonid is a key counter measure to the warmer waters caused by climate change. See more at whooshh.com .

U.S. Government non compliance with the Columbia River Tribes Treaty is much needed to be changed for the betterment of all life. What the U.S. calls progress is very vivid today that more harm for all life is impacted. Take the dams out and let Mother Nature live forever….pretty simple for me to see the resolution for this important nature law to live forever….Save the homeland and habitat for all salmon and steelhead and lamprey and trout forever….Love & Bless.

Is a bounty still in place on Ptychocheilus oregonensis? I would think that they would prey upon the juvenile shad.

Billions of dollars spent on countless studies to “save the salmon” and nothing much changes. Findings are generally predictable: it’s the sealions, the terns, the pike minnows, the cormorants, and now the shad. Like a wise old conservationist once said, “These aren’t salmon saving studies. They’re dam saving studies.” The reality of this situation is more than most people can bear, but it seems abundantly clear that Columbia/Snake river dams and salmon are not compatible. At this point we may not be able to truly restore salmon runs even if the dams are removed, but there’s one, hard, cold fact we need to acknowledge: these fish will never come close to reaching their potential as long as the dams are in place.

The count this year is almost 2 million fewer than last year. Varies a lot. Fall Chinook are getting through to the upper snake and a lot are coming through Bonneville the last week. 42,000 in one day.