Photo by Loren G. Davis

Archaeologists digging in western Idaho find some of the oldest evidence of human occupation in the Americas.

By Valerie Brown. Oct. 17, 2019. In the Columbia River Basin there are thousands of miles of gravelly banks that line the Big River’s major tributaries — rivers like the Salmon and the Payette, the Deschutes, the Clearwater, the Yakima and the Grande Ronde. These gravel bars form as sediment is carried downstream, and they shrink, shift and expand in response to geologic processes that occur over thousands of years. They also made attractive sites for the earliest humans in the region seeking freshwater, fish, and material to make stone tools with. As such, these layers upon layers of gravel contain all sorts of clues that can help us gain a better understanding of the region’s natural history, as well as the continuously developing narrative of human occupation in the Americas.

However, the Basin’s extreme geology — replete with floods, landslides and volcanic eruptions — has likely destroyed most evidence of ancient occupation, much to the chagrin of archaeologists.

“There’s probably a whole series of encampments or occupation areas from the mouth of the Columbia River all the way up” to the Salmon River that are impossible to locate, says Oregon State University professor Loren G. Davis…

…which makes his team’s excavation of artifacts from a gravel bar in western Idaho that much more remarkable.

Known as Cooper’s Ferry, the site is located along the Lower Salmon River at its confluence with Rock Creek. Davis first excavated a cache of stone points there in 1997, and a more thorough investigation of the site was launched about ten years ago. In the time since, Davis and his team have uncovered more stone tools (spear points, blades and other bifaces), as well as charcoal and bone fragments from ancient mammals.

Since 1997, students from across the country have participated in Davis’ annual 8-week archaeological field school at the Cooper’s Ferry site. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

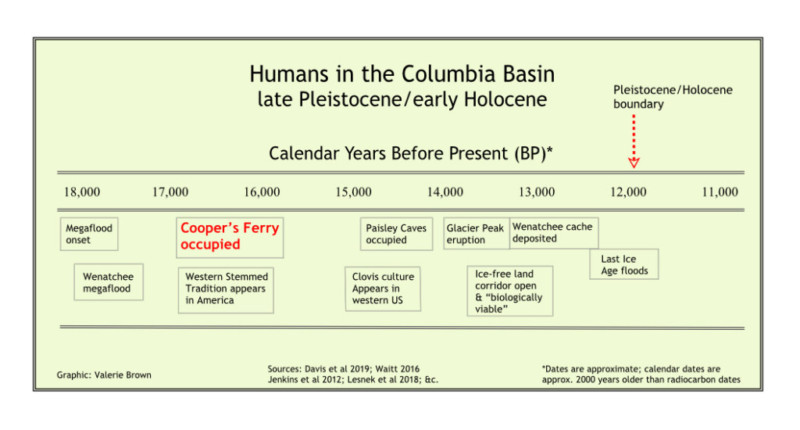

Using these artifacts and radiocarbon dating techniques as proof, Davis and his colleagues published a paper in the August 30 issue of Science showing that people lived in the region much earlier than had been supposed. They dated the earliest human presence to 16,500 years before the present (BP). This puts the first humans in North America at least 2,000 years earlier than previous estimates, and more deeply into the Pleistocene epoch, before the Ice Age ended and the era’s megafauna — mammoths, giant sloths and the like — went extinct*. These changes mark the transition to the current geological period: the Holocene (also known as the Anthropocene) epoch.

[*Note: the theory that humans are responsible for megafaunal extinction has been questioned by recent research, which blames climate change.]

The early date, provocative enough by itself, establishes two more fascinating points.

First, Davis’ team found bone fragments belonging to an extinct species of horse. In the northwestern U.S., the direct association of extinct animals with human artifacts has been exceedingly rare. The best established regional association before the Cooper’s Ferry site was the Paisley Caves in southeastern Oregon. Workers there have dated ancient spearpoints along with bison, horse and mastodon bones to about 14,000 years BP.

The second striking implication of the Cooper’s Ferry date is that it shows people were living in the region during the Ice Age, when massive ice dams occasionally formed and collapsed along river courses, causing around 100 megafloods throughout the Basin. This period occurred from about 17,000 years BP to 11,000 years BP — with the extensively researched and oft-cited Missoula Floods occurring between 15,000 and 13,000 years ago.

And while we don’t know exactly how people got to Idaho, the most obvious route would have been to follow the Columbia River inland. They would have encountered evidence of mega-floods everywhere, including the rumpled chaos at Cascade Locks and eastern Washington’s channeled scablands.

It’s impossible to know whether people at any of the archaeological sites in the Basin witnessed or fell victim to any one of the Ice Age floods, but U.S. Geological Survey geologist Richard Waitt has made a meticulous inventory of the floods by analyzing the great washes of gravel, sand and mud that swept sequentially through the region and formed places like the Pangborn bar in Wenatchee, Wash. A spectacular cache of spear points was found there in 1987. The cache was loosely embedded in post-flood windblown silt on top of flood debris dated to about 5,000 years earlier — close in geological terms, but not a match.

Still, the cache indicates that people did occupy the area during the latest and smallest floods. These people made their tools in the Clovis tradition, which appeared about 14,000 years BP and until recently was considered the oldest human culture in the Americas. The Wenatchee cache dates to about 13,000 years BP.

But the Cooper’s Ferry material pushes the human presence back to the main late Ice Age flood period. Waitt and Davis agree that the backflood from some torrents would have reached up the Salmon River. “You would have seen the river rise…about two miles downstream” from Cooper’s Ferry, Davis says. The water would have risen slowly enough that people could outwalk it, though, he adds.

They would also have had to cope with a climate that fluctuated pretty wildly during the later years of the melt-refreeze-flood cycle. At the Cooper’s Ferry site itself, the Davis team found relatively sparse evidence of the people’s diet, including a freshwater mussel shell and numerous as-yet unidentified mammal bone fragments.

Who’s here first?

How people reached the Americas has been a matter of vigorous dispute among archaeologists. Until recently, the prevailing narrative has been that people from Siberia and/or the Asian peninsulas trekked across Beringia (a land bridge between Russia and Alaska) during the Ice Age while sea levels were much lower, and followed an ice-free land corridor down the middle of the continent. But as research has progressed, this idea has become less plausible. It now appears people reached the Americas at least a thousand years before the ice-free corridor existed.

What looks more likely is a coastal route taken by people in small boats hugging the coastlines all the way around the Pacific. Although much of it is now underwater, there is evidence of human presence down the coasts of Washington, Oregon and California during the relevant period.

Bolstering this oceanic route theory is a connection drawn by the Davis team in their recent paper: that the Cooper’s Ferry tools belong to the Western Stemmed Tradition, which closely resembles the Japanese tool-making tradition of the same time period.

Thanks, but no thanks to “Euro-splaining”

So what do these implications mean for the native peoples of the region?

According to Nez Perce ethnographer Nakia Williamson-Cloud, the people who lived in North America before Europeans arrived tend to discount the idea that their ancestors came from somewhere else. The Nez Perce, whose original territory included the Cooper’s Ferry site, prefer to view the site as a continuously inhabited Nez Perce site, and they do not believe they have an oceangoing past.

“We know our habitation there goes back generations and generations,” Williamson-Cloud says. “The archaeology is there to illustrate how long our people have been on this landscape.” Calling it “paleo-Indian,” he adds, “is a way to disassociate us from a site that we know is a Nez Perce site. It insinuates that it was somebody else than us.”

The tribe feels an even deeper connection to the site, he says, because the discovery of bone fragments from an extinct horse suggests the tribe’s renowned equine skills predate their interaction with horses imported from Europe, and “shows that their relationship with the horse came full circle for the Nez Perce.”

Northwest tribes have also traditionally opposed any invasive physical testing of ancient human remains, and they have re-interred several skeletal remains found in the Northwest, including Kennewick Man and Buhl Woman. Williamson-Cloud says the Nez Perce would take the same position should any human remains be found within traditional Nez Perce territory.

In future discoveries, genetic material could be the best way to determine — from a scientific perspective — whether there is any gap between early humans and modern Native Americans. (Geneticists have extracted usable 50,000-year-old Neanderthal DNA from soil in Belgium, so this technique might be applicable in the future.)

More sites with more clues?

Many archaeologists concur that the geologically young character of the Columbia Basin works against finding more evidence of early human occupation. But on the other hand, the Basin may be the best place to look, since most of it is “sub-glacial” — meaning it was close to, but not under, the ice sheets, and thus the most obvious latitude to search for proof of the region’s earliest human inhabitants.

“I think it’s a fair enough assumption to think if people are at Cooper’s Ferry by 16,000 BP,” Davis says, “there are probably other places in the Columbia River basin” with evidence of earlier human occupation. But given past climate catastrophes, “One the of the hardest parts of archaeology is finding that sweet spot where the dirt is still preserved,” he adds.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock

Still, the Cooper’s Ferry site shows that there are signs of human occupation at elevations that were higher than where the floods reached. And even though Davis thinks his team has found the earliest level of human evidence at Cooper’s Ferry because their excavation reached the basalt bedrock, he admits that “we have to be careful not to assume we’ve found the oldest there is [just] because we ran out of dirt.”

“There are other parts of the canyons that have even older sediment,” he says. And the team has much more data from the site to analyze than was included in the current study, which focused on precise dating and tool technology.

And although we’ll never hear the trumpeting of mastodons roaming the grasslands, we can still imagine the Columbia Basin much as those ancient inhabitants experienced it: the astringent scent of sagebrush and juniper after a rain, the steppes, hills and mountains windswept and cold in winter, windswept and hot in summer, and heartbreakingly beautiful always.

How about a friendly competition of finding the biggest/oldest tree of various species in HR City and County?

Would be fun highlight the value of our trees.