The Dalles’ long relationship with aluminum continues with the largest air toxics fine in DEQ history

Aluminum logs produced from scrap aluminum at Hydro Extrusions LLC, The Dalles, OR. Photo by George Esteich

By Valerie Brown. April 23, 2020. On April 24, 2019, inspectors from the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency arrived at Hydro Extrusion USA, LLC (also known as The Dalles Cast) in The Dalles for an unannounced two-day inspection. As a result of their visit, the aluminum recycling company received the largest fine for air pollution in Oregon’s history — nearly $1.3 million.

The fine was triggered by violations of Title V of the federal Clean Air Act, which requires polluters to keep their hazardous emissions below certain levels. The agencies found that contaminated scrap, also called “dirty charge,” was the source of most of the violations. They also found that the company had failed to comply with several record-keeping and safety regulations for more than a year.

Aluminum is the most valuable material in the recycling industry, and it requires only five to eight percent of the energy required to process primary aluminum from bauxite ore or alumina. However, aluminum recycling, and recycling in general, are increasingly plagued by various contaminants that complicate the re-use of the desired materials. Some of the complexity stems from the additional air pollution created when the contaminants pass through the aluminum melting furnaces.

According to Laura Gleim, DEQ’s eastern region public affairs specialist, the agency does not know exactly what toxic pollutants were emitted from the dirty charge. She says that, in order to use dirty charge legally, the company would have to conduct source testing to determine which additional pollutants it would have to acquire permits for, and then install appropriate mechanisms to capture those pollutants.

“Part of why the fine was so high was because…they’re supposed to up front come to us and show us they can meet the applicable emissions for the dirty charge,” says Gleim. Hydro Extrusion did not respond to multiple requests by Columbia Insight for comment.

“A white-gray smoke”

The Hydro Extrusion building is a large open space containing four induction furnaces, two holder furnaces, and four homogenizing furnaces. According to the EPA inspection report, the inspectors witnessed billows of “white-gray smoke” filling the building headspace. When they inspected the bales of scrap aluminum awaiting reprocessing, they found that much of the metal “had a gray-black residue coating” which, when rubbed with a finger, produced a “gritty, greasy texture.”

White gray smoke fills the Hydro Extrusion building head space. Photo courtesy of Oregon DEQ

Although the inspectors did not identify the contamination, it is likely to have been materials like paint, lubrication, marker pen, or plastic, which are often hydrocarbon-based materials frequently mixed with scrap aluminum and, in principle, removed before the scrap is melted. Burning these materials can produce highly toxic compounds, which is why most furnaces have venting hoods above them. But the inspectors noted that the hoods in the Hydro Extrusion facility were ineffective, as they were not directly connected to the ductwork carrying emissions through the roof vents to the outside.

Variable chemistry

Even without dirty charge, aluminum recycling requires the use of hazardous materials. Normal operations entail adding various chemicals to alter the chemistry to the desired state and remove unwanted elements such as magnesium and hydrogen. The scrap is processed in batches tailored to the needs of the customer, so there is variation in the recipes.

Most additions are termed “flux.” A common flux powder is a mix of chloride and fluoride salts that prevents the aluminum from reacting chemically with nonmetals and captures unwanted elements. But these salts may react with the aluminum to form aluminum chloride and aluminum fluoride — both powerful respiratory irritants — which are supposed to be removed by the exhaust system.

And these are just two of the 188 toxic air pollutants the EPA regulates under the Clean Air Act. For secondary aluminum plants, other emissions of concern also include dioxins, furans, various organic (carbon-based) compounds, and particulates. The health effects of exposures to these substances, the EPA says, “can include cancer, respiratory irritation, and damage to the nervous system.”

Decades in The Dalles

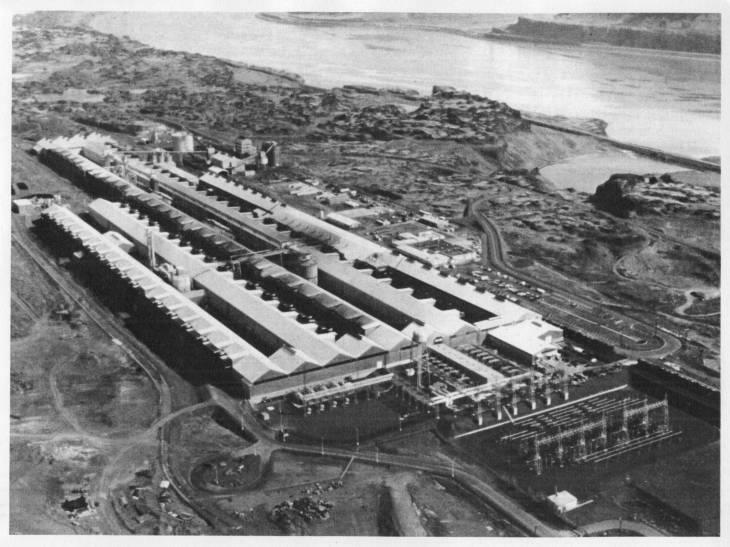

Aluminum processing in The Dalles has a long history. A full ore/alumina smelter was built in the 1950s by Harvey Aluminum, a California company, and for a while the smelter was the largest employer in the city.

Martin Marietta bought Harvey in 1970, but as environmental costs mounted up, The Dalles plant — then much bigger than the current recycling facility — became a Superfund site. It was removed from the National Priorities List in 1996, but is still monitored because its soils contained cyanide, fluoride, asbestos, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and arsenic, and groundwater on the site contained cyanide and fluoride. Responsibility for the Superfund pollution remains with the current owner, Lockheed Martin, which merged with Martin Marietta in 1995.

Martin Marietta Aluminum Plant, The Dalles. Photo courtesy of Washington Rural Heritage

The financial and energy crises of the late 1970s, mid-1980s and early 2000s collapsed the primary aluminum market in the Columbia Basin, which at its peak had ten operating smelters. After that, a handful of locals, including employees, bought and ran some of the smelters, but they found it difficult to turn a profit. The Dalles’ long relationship with aluminum continues with the largest air toxics fine in DEQ history.

In 2015, the remaining active plant in The Dalles, Northwest Aluminum Specialties Inc., became the ninth North American location of a Norwegian company, Sapa Extrusions. And in 2017, Sapa was bought by Hydro Extrusions, LLC, another Norwegian multinational operating in 40 countries with 35,000 employees.

The bright side?

According to the DEQ, the company knew it was violating the law. But in the time since the fines were levied, it has begun to correct some of these problems.

One former Hydro employee noted that before the Norwegian companies took over, the chief safety gear available to workers while running the furnaces, adding flux, and pouring molten aluminum into molds was long-sleeved shirts. (The employee declined to be identified publicly out of concern over reprisals.) After the Norwegian companies assumed ownership, he said, the employees were issued fire-resistant safety suits and procedures were put in writing. And, according to Gleim, the company has engaged a consultant and is “working to improve environmental compliance and environmental management procedures.”

Why it matters

The recycling plant in The Dalles is much smaller than any of the ten primary aluminum smelters that used to dot the Columbia Basin. The environmental and occupational problems associated with aluminum recycling are less egregious than those produced by smelters, and the plant’s 70 employees are far fewer than the hundreds the smelter employed at its peak. The energy demands of recycling are also minuscule compared to primary smelting, and thus recycling emits far fewer greenhouse gases.

From the Dalles Chronicle archives, workers at the Western Aluminum Producers Plant manufacture aluminum ingots in 1979.

Still, its emissions add to the pollutants in The Dalles, whose downtown is sandwiched between two highly contaminated industrial sites. As we reported in 2017, the Amerities railroad tie plant in The Dalles has come under fire for its emissions of naphthalene and other pollutants. (That site sits on the Union Pacific Superfund site about three and a half miles east of Hydro.)

Air toxics became a political hot potato in 2016, when Portland residents learned that Bullseye Glass was emitting significant pollutants in a residential neighborhood. In response, the state created the Cleaner Air Oregon initiative, which included a three-year air toxics monitoring project at five locations, including the Wasco County Library in The Dalles. Earlier this year, the DEQ released the results for 2018, and The Dalles’ levels of naphthalene, acetaldehyde, and formaldehyde — all carcinogens — were significantly higher than any other site. The report stated that these compounds and three others “are present at levels of concern in both urban and rural areas.”

Does Hydro bear any responsibility for those pollutant levels? It’s complicated. The site’s 2016 DEQ permit lists naphthalene and formaldehyde as “potential” emissions, but naphthalene can also be emitted by both aluminum recycling and railroad tie factories, and wildfires can produce significant levels of all three PAHs. And as Gleim explains: “It’s difficult to pinpoint exact sources from this kind of monitoring data.”

Stay tuned

For many Gorge residents, the recent DEQ and EPA action, while dramatic, may be less than satisfactory.

Rachel Najjar, a former resident of The Dalles and a co-founder of The Dalles Air Coalition, was “shocked” by the size of the DEQ fine, but believes regulatory enforcement is inconsistent and patchy. “It feels like they pick and choose polluters that they want to fine, instead of having clear, health-based regulations for all polluters,” Najjar said in an email.

“Industry needs to be paying the price with money, instead of the community paying for it with their lives and health,” she continued.

But Hydro may never have to pay the full amount of the DEQ fine. The company is appealing the DEQ’s order and fine, and is negotiating a settlement with the state.

Thank you for covering this story! And, please follow up. The local paper doesn’t get investigative, doesn’t write about big unseen issues affecting quality of life in the eastern Gorge, and doesn’t do much for following up. And now that our local Gorge papers are being merged, there’s likely to be even less hard-news coverage. So it’s on you, Columbia Insight! Thanks again.

Thank you for the insight ( no pun) on the terrible air quality in The Dalles. Between the aluminum plant and the stench from Amerities (railroad tie plant) it’s terrible that we have to breath this foul air. People move here and 6months later have to move because of the health effects on their body.

Whenever you smell funky air in The Dalles, call and complain. I smelled the mothball naphthalene from Amerities today and called (541-296-1808). They have to report it to Oregon DEQ. The more complaints they get, perhaps DEQ will hold their feet to the fire.

I don’t think it’s asking too much to smell the lilacs instead of chemicals during the springtime.

So the OR DEQ didn’t know what toxins were being released, but they fined the company anyway? Sounds like the company should have sued the damned state. Why would any judge allow a fine if the state cannot determine if the emissions are toxic. If it was a white gas, it may well have been steam.

It is a wonderful article stating the pollution from aluminum still an issue in the dalles, which can be the best option as per your need. I like how you have researched and presented these exact points so clearly.If possible visit this website Eagleengineering.co.nz to gain more idea or tips on the same.

Back 1967 I worked at the Aluminum Extrusion Plant along I35 in Richardson, Tx where I only worked a few months before realizing I was working within a plant that was easy to see it could kill anyone, now, or 50yrs later.