Conservation and hunting groups worry that solar facilities on public lands will disrupt wildlife corridors

Hot spots: Sites like the Dry Lake Solar Energy Zone in Nevada are chosen for the Western Solar Plan for their high solar potential. Photo: BLM

By Kendra Chamberlain. January 23, 2024. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management has opened up its 2012 Western Solar Plan to include Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana. The original Western Solar Plan identified only Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah as areas for solar development.

The expanded plan proposes opening 22 million acres of public land across all 11 states for solar development.

The agency says it has identified 700,00 acres of that land as ideal for solar development because it is within 10 miles of existing or planned transmission lines, has comparatively few sensitive resources and offers minimal conflict with other uses of public lands.

The BLM manages roughly 10 million acres of land in Idaho and 12.5 million in Oregon. There’s relatively little BLM land in Washington.

The BLM announced the expansion of the plan last week.

The Biden administration has set a target of a fully renewable energy grid by 2035.

Disrupting wildlife migration

The proposal, which could see enough solar development to power tens of millions of homes, has been touted as an important step in the Biden Administration’s clean energy transition.

But there’s a drawback: some of the land proposed for solar development is prime winter range for mule deer and other big game.

Concern has been growing over conflicts between new solar-energy facilities and wildlife, as Columbia Insight reported last year.

BLM’s solar proposal may further fragment what’s left of the wildlife corridors big game use to migrate throughout the year.

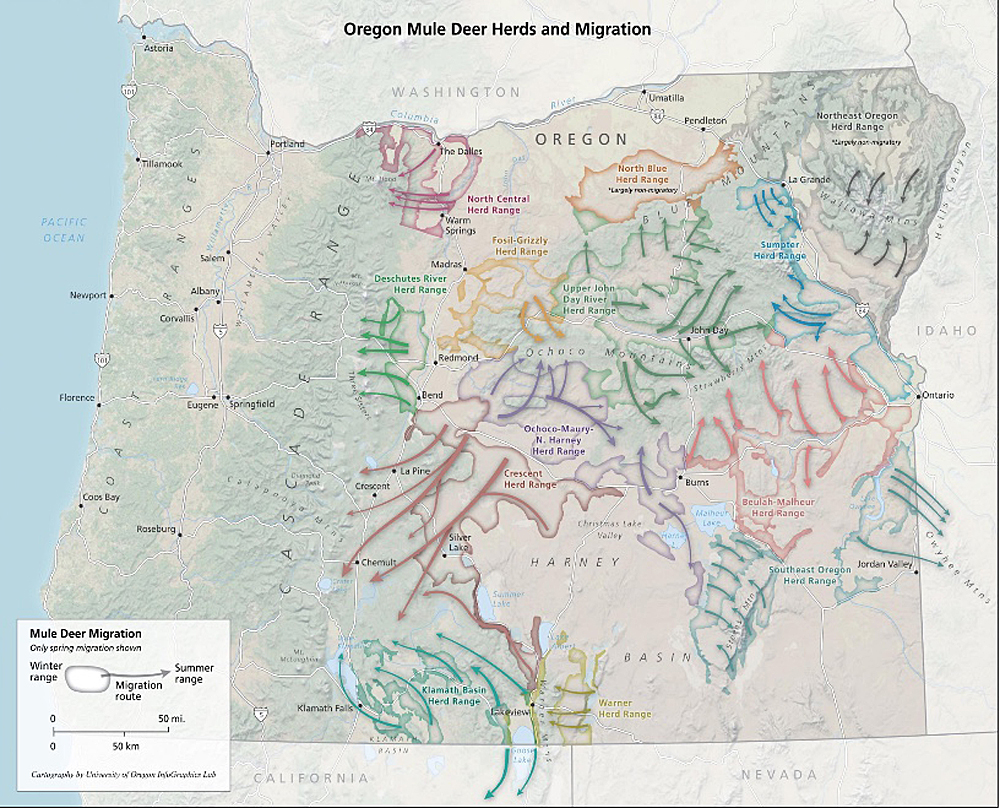

Moving on: East of the Cascades, upwards of 98% of mule deer in Oregon are migratory. Map: ODFW

“All these utility-scale solar farms are required to have external fences around them,” said Mike Totey, conservation director at Oregon Hunters Association (OHA). “Once that occurs, basically that area is off-limits for big game.”

Mule deer are particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation; their populations are declining across the West.

Biologists point to a host of factors contributing to the decline, including disease and drought. But habitat fragmentation across Oregon, Washington and Idaho is hitting the species especially hard.

Mule deer spend their winters in lower elevation sage-steppe and juniper woodlands and move into the higher elevations during the spring and summer to raise fawns and fatten up.

Migrating mule deer have what Totey called “site fidelity” in their seasonal routes.

“They’ll move to an area for summer range … and they’ll take another path back down to that winter range and essentially repeat that cycle in those same areas along those same pathways, those travel corridors, every single year,” Totey told Columbia Insight.

While BLM has recently streamlined its siting process for solar development under the Western Solar Plan, Totey wants wildlife corridor fragmentation to be considered during future NEPA process for specific solar projects in the region.

“One of the things that we just have not really got our arms around is the cumulative impact [of these solar farms],” he said. “What happens when you put the next one in? There’s been—as near as I can find—really, very little work to try and determine what those cumulative impacts are.”