Employing a “life and property first” policy, firefighters saved cabins with a mile-long fireline, but scars remain

Why we fight: Protecting lives and property are the first priorities of fire fighters. But saving ancient beauties like these was also important for fire fighters working last summer’s Big Hollow Fire in Washington’s Trapper Creek Wilderness. Photo by Jurgen Hess

By Jurgen Hess. November 26, 2020. As I drive slowly past the site of a September 9 roadblock, a time when wildfires are ravaging the Columbia River Basin, I’m pumped with anticipation. I’m heading into a prohibited zone, but I’m not breaking any rules.

I’m on the way to a meeting with two U.S. Forest Service firefighters who have agreed to take me into the fire zone to see a burnout line established as a part of firefighting actions on the Big Hollow Fire. The fire is in the Trapper Creek Wilderness, part of Washington’s Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

Moving through the woods, my senses are alert to the damage fires wreak on the landscape, but also to the damage caused by human efforts to contain it.

I wonder if somewhere up ahead I’ll find a massive clear cut leading into the Trapper Creek Wilderness. On previous fires I’ve seen catlines (firebreaks created by bulldozers or other tracked vehicles with a blade mounted on the front) that ended up creating as much long-term impact on the land as the fires themselves.

MORE: Trapper Creek Wilderness threatened by fire

Anyone who visits the Trapper Creek Wilderness can’t help but feel awestruck. Trees tower as high as 150 feet, as tall as 15-story buildings.

But perhaps more than others might, I enter these woods with a special feeling. In 2014, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, I’d spent 12 months photographing the Trapper Creek Wilderness. I’d hiked in every month—in snowshoes across drifts as deep as three feet, in pouring rain, packing 30 or more pounds of photo gear.

I’d gotten to know and love every nook, cranny and creature of these woods, even the giant banana slugs that thrive in a rainforest that receives over 100 inches of rainfall each year. I’d watched streams that were almost completely dry in August morph into roaring currents three-feet deep in December. The Trapper Creek Wilderness became my “private” piece of heaven, a place to slow down, absorb nature at its own pace, let the slugs be my teachers.

This past summer the Big Hollow Fire roared into the Trapper Creek Wilderness—Dante’s Inferno. Almost immediately I began worrying that some of the 400-year-old Douglas firs I’d photographed six years before—survivors of the 1902 Yacolt Fire—might have already been cut down by fire fighters attempting to create a burnout line.

Fire man

I’m a fire chaser. In previous years, like 2017’s Eagle Creek Fire, I’d put on my fire clothes, get vetted by fire managers and get out to the front lines to photograph and report on the action. I give educational talks on fire.

That changed with COVID-19. Only firefighters are allowed in fire zones now; no media.

To compensate, last summer I joined Inciweb Zoom sessions conducted by the Big Hollow Fire incident command team. Inciweb is an interagency all-risk incident web information system run by the USFS. It’s an invaluable source of information for anyone wanting updates on fires and other emergencies.

Hot shoot: The author documents the mop-up stage of the 2013 Blackburn Fire east of The Dalles, Oregon. Photo by Chris Friend/ODF

On the Zoom sessions I paid attention, took notes, then relayed my unofficial reports to concerned friends and colleagues.

I’d felt compelled to do this, but it wasn’t the same as being on the ground with the smoke, flames, adrenalin and wet armpits.

I was determined to see for myself the damage firefighting had brought to the Trapper Creek Wilderness and adjacent area. So I started making calls to USFS officials. Eventually, persistence paid off, and I was able to arrange a visit.

Property is priority

The area of the Big Hollow Fire remains closed to the public. Intimidating signs are posted at trailheads and road entries, warning people away.

I meet my guides for the day. Pete Nelson and Christian Buettner are with the Mt. Adams Ranger District, Gifford Pinchot National Forest, so this is their home turf. Buettner was a fire boss for the crews clearing the trail fuel break. Nelson is the Mt. Adams District assistant fire management officer.

End of the line: Forest Service guides Christian Buettner (left) and Pete Nelson inspect the western end of the burnout line at the Trapper Creek Wilderness boundary. Photo by Jurgen Hess

After saying our hellos, we zip up rain pants and waterproofs and start walking. Starting at the trailhead outside the Trapper Creek Wilderness, we walk west for a mile to the wilderness boundary, stopping often to observe and talk about the clearing work done by fire crews.

The burnout line was meant to stop the fire’s advance by robbing it of fuel. When the line was put in the fire was burning on a hillside, but had entered the Trapper Creek Wilderness.

The objective was to protect 44 cabins at a place called Government Mineral Springs. Sited on land leased from the Forest Service, the private cabins sit about 200 feet downhill from the burnout line. In addition to the burnout line, sprinklers were set up around the cabins. A lot of expense and work went into saving the cabins.

The small- to medium-size cabins were constructed in the 1950s, and have either been replaced, updated or altered over the years. It’s hard to call them historic.

“Life and property first. Trees grow back. It’s the right thing to do,” says Buettner.

Nelson nods. “Life and property first” is the guiding policy for all wildland firefighting agencies.

“It would have looked bad if we didn’t (put in the line),” Nelson adds.

How Firewise are we?

As we inspect the burnout line I look downhill to the cabins. Giant trees and native brush surround and overhang the structures. Some cabins are hard to see through the foliage. Could owners have done some vegetation removal to lower their fire risk?

“We have to get Forest Service approval to cut anything,” says Jerry Franklin, a cabin owner, University of Washington forest ecology professor and Pacific Northwest old growth guru.

Brush with danger: Trees and growth next to cabins contributes to fire-safety issues at Government Mineral Springs. Photo by Jurgen Hess

“We want to keep the area looking as natural as possible,” says David Wickwire, Mt. Adams Ranger District recreation program manager. “Owners like their privacy.”

This may be true, but it doesn’t make it fire safe.

“That naturalness certainly doesn’t meet national fire safety policy, called Firewise, for clearing around houses,” says Susan Saul, conservationist and one of the founders of the Trapper Creek Wilderness. “They preach Firewise gospel here, but they don’t practice what they preach.”

The Big Hollow Fire affected about 30% of the Trapper Creek Wilderness, which covers 5,970 acres. The fire is currently classified as 70% contained.

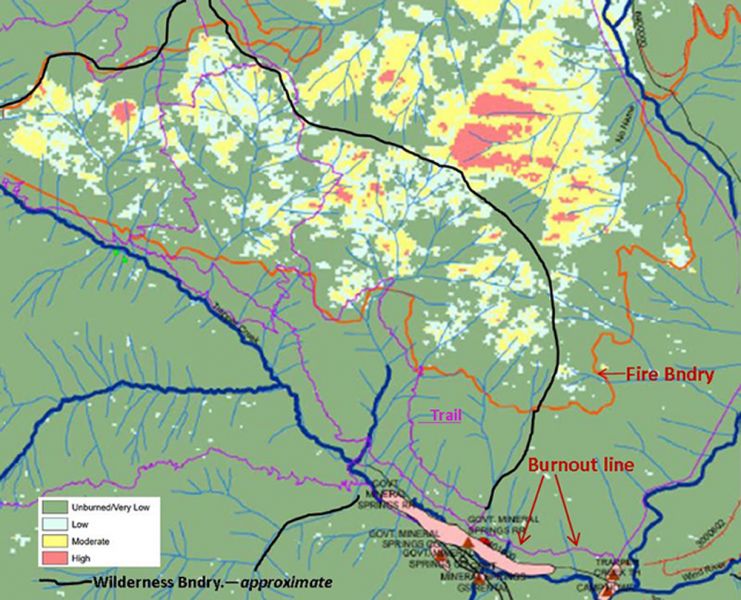

As it turned out, the fire stayed far away from the cabins. None were damaged by the Big Hollow Fire. The blaze stayed high on a ridge (see map below). Rain put out the fire. The burnout line was never used.

Although the area is closed to most of the public, the cabins and immediate area are open to cabin owners. It’s a little strange within the fire zone to see cars parked next to many of them, smoke wafting from the chimneys.

Because USFS recreation managers are concerned that burned trees could fall and harm hikers, the Trapper Creek Wilderness remains closed. It will likely reopen in Spring 2021.

Visible scars

The damage isn’t as bad as it could have been.

“It was a low-intensity fire, mainly staying low and on the ground,” says District Ranger Erin Black. “The (burnout line) is like a heavy trail maintenance, fairly light on the land. It cleaned up lots of brush and small trees. But see what you think.”

So what do I think? My critical eye is honed by having been a Forest Service manager for 34 years. I’ve seen many mistakes in the rush to put out fires. But nothing major sticks out at me here.

Big Hollow Fire severity map. The Government Mineral Springs cabins are located in the pink area. The burnout line on Trail 192 is indicated outside the wilderness area. Map by Inciweb

The burnout line was constructed on Trail 192—that’s the main access trail into the wilderness area. It attracts lots of hikers. The burnout line starts at the trailhead and runs a mile west to the wilderness boundary. No clearing was done in the wilderness area itself.

Mainly low shrubs and brush were cut and thrown on the green side of the burnout line. Dead and dying trees on the black side (the burned side of the break) were cut and thrown over to the green side or dropped in place.

Only hand tools were used. Much of the trail corridor was left as-is, with no cutting at all.

There are scars. Hikers will notice cut branches with dead leaves for several years, as well as stumps from cut trees. But Black is right—the damage does look like a heavy trail maintenance effort.

The brush and tree clearing on the trail was light on the land and will leave little lasting impact. I’d call it a good job.

What hikers and other users will think of it remains to be seen.

Photojournalist Jurgen Hess is treasurer/secretary of Columbia Insight. He spent 34 years as a U.S. Forest Service manager.