A report assembled by more than 30 stakeholders, Vision Around the Mountain aims to decrease congestion around Mount Hood with a holistic approach to public transportation

Uh, no: Finding full parking lots at ski resorts, drivers along U.S. 26 have begun illegally parking on highway shoulders. Photo: ODOT, December 2020

By Chuck Thompson. December 2, 2021. If you’re planning to ski, snowshoe, sled or simply drive anywhere around Mount Hood this winter get ready to blow through a season’s greetings worth of profanities.

Then trying to park.

It’s become the norm for ski resort and trailhead lots to reach full capacity as early as 7 a.m. (earlier on powder days), leaving aggravated drivers with equally poor choices—just pull over and park on the roadside or turn around and crawl back home, sometimes for hours. Extreme congestion in Sno-Park lots has resulted in hazardous parking along main thoroughfares and longer response times for emergency services.

Forest rangers are exhausted, drivers and passengers are fed up, trailheads are a zoo.

Although relevant traffic data isn’t yet available, the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) confirms its getting worse.

“The winter of 2020 was anecdotally one of the most congested times up on the mountain according to what we’re hearing from our partners,” says Jason Kelly, ODOT principal planner for Region 1, which includes Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas and Hood River counties.

MORE: Electric cars and dams: An uncomfortable connection

Now, the Oregon Department of Transportation has come up with a plan—more accurately “a vision”—to address the often hellish traffic around Mount Hood.

Unveiled in August to little fanfare, it’s called Vision Around the Mountain or VAM.

If implemented, VAM could change the way we use the roadways around Mount Hood.

If not, it might simply be added to the growing mountain of well-intended ideas to relieve congestion around the state’s marquee peak.

VAM plan

Vision Around the Mountain’s stated goal is both simple and a little vague: “Establish a long-term, regional transit vision for public transportation serving Mount Hood via OR 35, U.S. 26 and I-84.”

To pull this off, VAM outlines some 85 actions broken down into eight categories. These range from Planning & Policy to Transit Routes to Passenger Convenience.

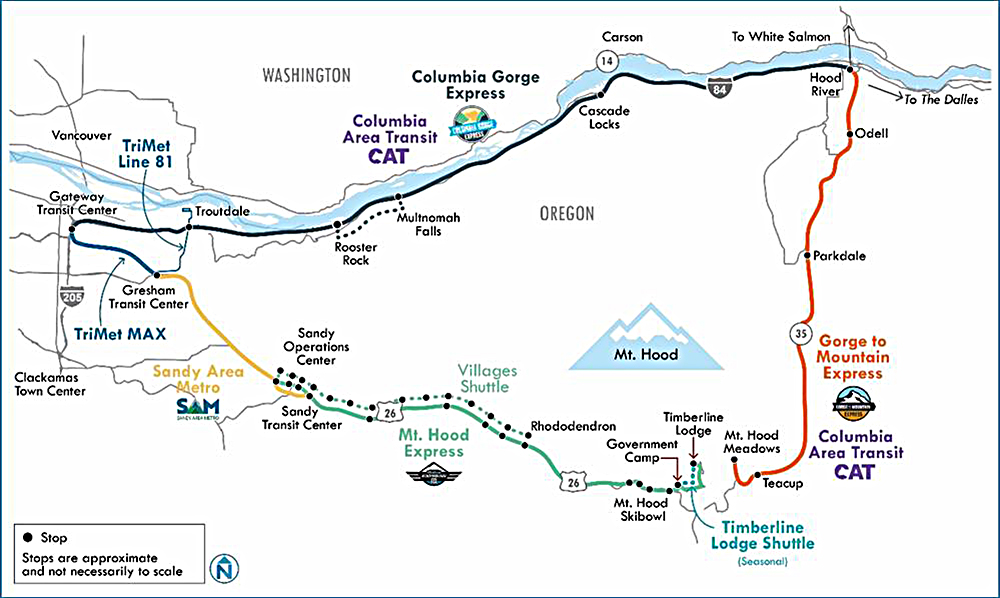

The primary idea pivots around the expansion and improved coordination of operations provided by the existing network of mountain transportation providers, including Mt. Hood Express and Gorge-To-Mountain Express Service. Together, a number of entities would one day provide frequent, all-day, year-round service along U.S. Route 26 and Oregon Route 35.

VAM also maps out a Mountain Transit Circulator to allow hop on/off service to popular recreation spots, presumably including ski resorts and trailheads, although ODOT doesn’t specify.

Current transportation network, August 2021. Image: ODOT

VAM proposed transportation network. Image: ODOT

According to Kelly, the VAM project leader, the challenge now is to turn the momentum gained from the visioning process into results.

“The bottom line is that more people are coming into the Portland metro region and that compounds existing issues—the vision plan is a first step outlining actionable items as a way forward,” Kelly tells Columbia Insight.

The clock is ticking. Kelly points to a recent population forecast for the Portland metro area showing an estimated in-migration of 400,000-600,000 people by 2040-50.

Doable or dud?

The VAM executive summary is a curious document from which to divine information. Over just 12 pages, the word “vision” appears 60 times.

Specifics on how to achieve its vision are in slimmer supply. Ideas that do appear sometimes feel quixotic. And contradictory.

For example, one strategy is to “Scale service levels to demand.” Sounds reasonable. But another strategy calls for “Run(ning) service frequently enough so people do not need a schedule.” Scaling back services in times of low demand would seem to subvert the idea of service so frequent the system runs like a Manhattan subway.

“The interest is to have a program that is convenient and accessible to the point where you know it’s going to arrive,” says Kelly.

MORE: Two charts show COVID-19 impact on air quality

Cost is another issue to be solved.

“It is estimated that the annual operating cost of all existing (transportation) providers is approximately $2 million/year in 2021 but to operate the core network Vision would be close to $5 million/year for enhanced service frequencies operating every day and year-round,” reads the report. “In addition to annual operating costs, the full Vision would also require additional capital costs for new vehicles, new transit hubs, park and ride facilities, etc.”

The particulars of “etc.” notwithstanding, how might more than doubling, or even tripling, existing expenditures be achieved?

“Identifying the right mix of funding requires much more exploration,” reads the report, which goes on to suggest congestion pricing, leveraging higher local matches, added private contributions and increasing Sno-Park fees might help meet higher operating costs.

“This project was not an exercise in feasibility,” says Kelly. “It’s not prescriptive. VAM is really a roadmap to show how all the partners can collaborate and work together.

“It’s not a plan, it’s not a publicly adopted document, it’s partners that came together and talked about how to better coordinate and build out a system that achieves the needs of what we envision transit on the mountain (could be).”

Why VAM?

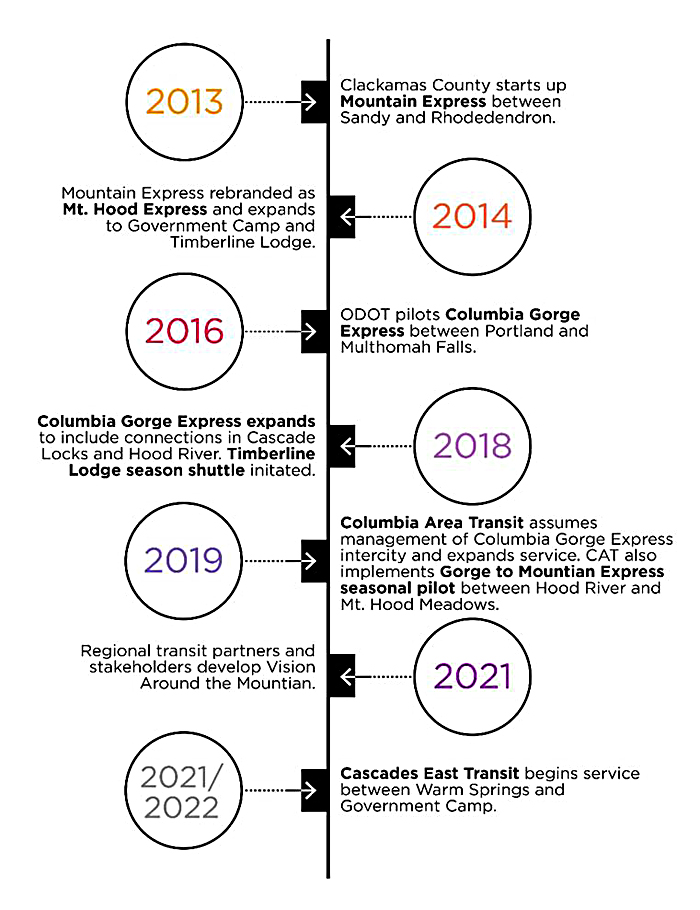

Crowded roadways around Mount Hood have been addressed before, notably with the 2014 Mt. Hood Multimodal Transportation Plan, which intended to “help reduce congestion in the short-term (five years), as well as long-term (15 years).”

In 2016, the Federal Highway Administration voiced a desire for better coordination and connectivity among public transportation providers. Four of the five operators that provide public transit around Mount Hood—Columbia Area Transit, Sandy Area Metro, Mt. Hood Express, Timberline Resort Shuttle—receive Federal Lands Access Program funds.

The Federal Highway Administration wanted improvement. So it granted ODOT funds to conduct a “vision process” as a first step.

Kelly estimates $148,000 was spent producing the report, including the federal grant and additional regional funds.

Recent growth in public transportation options around Mount Hood. Image: ODOT

To initiate the process, Kelly coordinated more than 30 stakeholders, including federal agencies, state, city and county officials, public transportation providers, tourism bureaus and ski resorts. He called upon participants to develop a vision for a modernized transportation system—one that provides equitable, convenient and enjoyable public transit and access throughout Mount Hood and the Columbia Gorge.

The process was unconstrained by questions of budgets and funding, focusing instead on wants, needs and goals.

The group focused on two primary transit corridors: Oregon Route 35 between Hood River and Mount Hood, and U.S. Route 26 between Portland and Mount Hood. It also took into account the critical role of I-84.

The process included four workshops, multiple working groups and stakeholder discussions.

The Vision Around The Mountain report was released in August 2021.

Kelly describes VAM as a navigation system pointing toward an endgame.

“It’s very aspirational,” he says.

Will the public go public?

As noted above, we’ve heard big talk before about minimizing traffic around Mount Hood.

The key to pulling it off is those two words in the middle of VAM’s primary goal: public transportation.

So far, the public has proven largely resistant to giving up the convenience and independence their cars provide.

MORE: Only one thing will preserve post-COVID environmental gains

Can VAM—bolstered by an increasingly untenable traffic situation—help change that?

An immediate indication that VAM’s aspirations may not be off target—a long overdue plan to transport workers in Warm Springs to Mount Hood via a Cascades East Transit (CET) route is coming to fruition in partnership with the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. The CET service will provide a car-free, employment shuttle between Warm Springs and Government Camp for tribal workers during winter 2021-22.

However, that service would likely impact only about 25-35 workers. And CET told Columbia Insight this week it hasn’t yet initiated the service because it’s been unable to find a qualified driver.

The rest remains to be seen—or envisioned.

Chuck Thompson is editor of Columbia Insight.

There should be data available from CAT on how many riders they had up to Meadows for 2019 and 2020. It would also be good to see the data in Clackamas for Mt. Hood Express ridership. Parking congestion can be a major motivator to taking public transit. Add in the opportunity to avoid having to put on snow tires and you may get a lot of people from Portland, and Hood River, taking the bus.

What’s the point of your comment?

What a stupid idea. This has already been tried and failed in many other places. I remember when they did that in McKinley Park Alaska. It didn’t work there and they had way less people. In an effort to save money they only had so many busses and drivers available so the wait time was long. Thankfully I had proper near Wonder Lake so I didn’t have to rely on the bus and could drive in in my truck.