Two years after a grizzly recovery program got turfed, a new one brings hopes—and questions—out of hibernation

Home boy: Grizzlies once roamed the North Cascades. Might they again? Photo: Terry Tollefsbol/NPS

By Jordan Rane. November 17, 2022. At the beginning of this year, Columbia Insight reported on a move by Trump administration officials to terminate a long-running government study looking at the feasibility of reintroducing grizzlies to the North Cascades.

That decision appeared “final.”

But last week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Park Service put the plan to consider restoring grizzlies in Washington’s North Cascades back on the table.

It’s also back to square one, or thereabouts, after years of study on grizzly restoration in the region.

“The National Park Service (NPS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) are jointly preparing an environmental impact statement (EIS) for the North Cascades Ecosystem Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan to determine how to restore the grizzly bear to the North Cascades Ecosystem (NCE), a portion of its historical range,” states a Federal Register Notice of Intent released by the Department of the Interior on Nov. 14. “Action is needed to restore grizzly bears to the NCE because they are functionally extirpated from the ecosystem, and restoration there will contribute to overall grizzly bear recovery.”

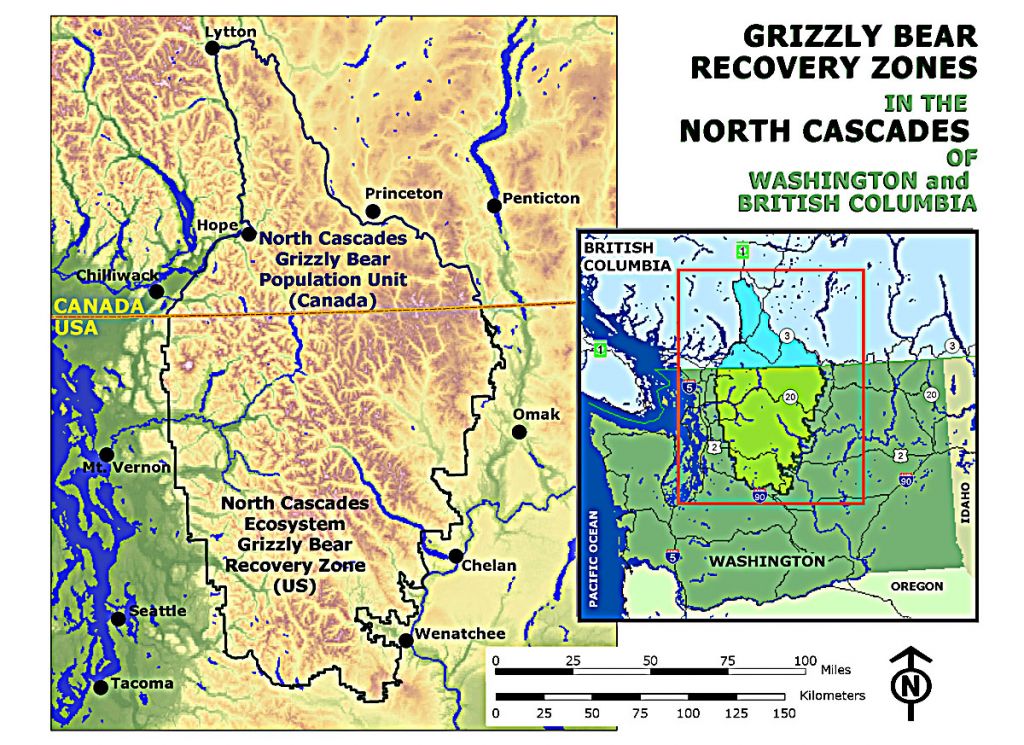

Of six designated grizzly bear recovery zones spread throughout large wilderness areas in Washington, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, Washington’s Cascades region is considered the most imperiled grizzly habitat in the United States today.

Long recovery road

Wildlife biologists believe there’s currently no functioning grizzly population in the Cascades at all.

In a roughly 10,000-square-mile area of north-central Washington—focused around North Cascades National Park and surrounding national forestland—thousands of grizzlies once roamed before being largely killed off by the mid-1800s.

Studies dating to the early 1990s have estimated the area today could sustain a viable population of 250-300 grizzly bears.

Grizzly country? North Cascades National Park sure looks like it. Photo: Autumn Carlsen/NPS

Any proposal to restore the animal here would require transplanting a modest number from “source populations,” primarily in northwest Montana—home to one of the largest grizzly populations in the Lower 48—as well as interior British Columbia.

“Approximately 3 to 7 captured grizzly bears would be released into the North Cascades Ecosystem each year over roughly 5 to 10 years, with a goal of establishing an initial population of 25 grizzly bears,” states the DOI notice, outlining one possible scenario that would need to be ratified after the completion of an EIS. An adaptive management phase would then permit additional bears to be released into the ecosystem over time.

The action—if ultimately proposed—could be expected to produce a population of about 200 grizzly bears within the next century, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service.

“This new action by the FWS and NPS is a step in the right direction to put grizzly bears back on the path to recovery,” says Andrea Zaccardi, carnivore conservation legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity, which filed a legal challenge in federal district court against the two agencies in December 2020 when the last recovery program was terminated. “Without a helping hand, grizzly bears are likely to disappear from the Pacific Northwest.”

“Grizzly bear restoration is the realization of a dream of many people and the bears’ return to the Cascades will be a success story that enriches our communities, indigenous cultures and the ecological fabric of our wild areas,” wrote Conservation Northwest in a Nov. 16 email to its supporters

Grizzly opposition

Wherever this latest path leads the future of grizzlies in the North Cascades, it arrives on the heels many previous, painstaking steps.

Voluminous studies date to the 1990s when the USFWS first identified the area (among others) as a recovery zone in the Northwest.

In the DOI’s latest notice, those past efforts are abbreviated into a single, acronym-stuffed sentence: “The NPS and the FWS previously proposed to restore grizzly bears to the NCE and produced a draft EIS for public review and comment in 2017.”

Potential grizzly recovery area as determined by government agencies. Map: USFWS

Commencing in 2015, the most recent study involved years of research, field work, scoping of over 100,000 public comments, a draft EIS several inches thick and untold tax dollars. It was nearing completion by mid-2020.

That’s when the DOI under former Secretary David L. Bernhardt abruptly pulled the plug on the whole thing.

“The Trump Administration is committed to being a good neighbor, and the people who live and work in North Central Washington have made their voices clear that they do not want grizzly bears reintroduced into the North Cascades,” Bernhardt stated in a press release, ending the study.

“The Trump administration’s rash termination of these plans forced us to launch a legal challenge,” countered the Center for Biological Diversity, claiming that federal officials in so doing had violated the Endangered Species Act.

In Washington, grizzly bear status was bumped to “endangered” shortly after being federally listed as “threatened” in 1975.

The Center’s lawsuit would hibernate for two years on lingering—and dimming—hopes that the two agencies under the Biden administration would resume the grizzly recovery study without the need for litigation.

“Settlement talks were going extremely slow and we never got any proposal from them,” Zaccardi told Columbia Insight last week. “The original hope was that they’d be amenable to more real discussion and action than there’s been to date.”

In early October, the Center ramped up its original lawsuit by filing an Amended Complaint with the Department of Justice.

DOI countered with a Motion to Dismiss on Nov. 4.

Surprise announcement

In the midst of what’s become a stoked legal battle, last week’s announcement that the two agencies will be commencing a new grizzly bear recovery program in the Cascades was unexpected. At least by the plaintiff.

“It was a complete surprise,” says Zaccardi. “FWS and NPS know we have this lawsuit, and so I hope this actually means they have an eye toward avoiding litigation—and that this latest step is a positive one in the recovery of grizzly bears.

Walk in the park: Grizzlies are a common site in places like Yellowstone National Park. Photo: Kim Keating/USGS

“They could’ve just overturned the determination in 2020 and moved forward with the existing environmental impact statement. They did say they’ll be considering all those previous comments received since 2015 from that draft EIS, but essentially it looks like what they’ve chosen to do here is start the entire process over.”

How many more years of EIS-wrangling will it take to decide whether or not grizzlies will make it back to Washington?

“Best case scenario, we’re looking at (about) a year before there are any decisions about grizzly bears in the North Cascades,” says Zaccardi. “But right now, no one knows.”

For information about the public scoping process, virtual public meetings and submission of comments, contact the agency website here.

Neither the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or National Park Service responded to interview requests from Columbia Insight for this story. Should either agency provide a response, the article will be updated.

Grizzly bears have a right to have a viable population on earth. Are the dangerous? Of course. But far less than humans with so many shootings. Humans with guns-now that’s something to worry about.

Good story Jordan. I’m hoping FWS &NPS will do the right thing. The ESA requires restoration of the grizzly population.