DarkSky Oregon is lobbying Columbia River Gorge communities to adopt policies that would reduce nighttime illumination

Night lights: Looking east from Burdoin Mountain across the Columbia River at the lights of Mosier, Ore. The bright, white glow on the horizon (center) is the light dome over The Dalles, Ore. The bright spot to the left at river level is Lyle, Wash. The orange glow on the horizon left of Lyle is from Goldendale, Wash., 30 miles distant with a contribution from Washington’s Tri Cities, 120 miles distant. Photo: Mike McKeag

By Jim Drake. July 18, 2024. Two Gorge residents in Oregon are trying to convince officials that light pollution is on the rise and that adopting “dark sky” policies for outdoor lighting will help bring traditional nighttime back to the Columbia River Gorge.

Mike Hendricks of Hood River and Michael McKeag of Mosier have been organizing community outreach programs and collecting years of nighttime sky-quality data to promote the work of DarkSky Oregon, a chapter of DarkSky International, dedicated to reducing light pollution “for the health, safety and well-being of all life.”

According to Hendricks, the view of the night sky is better in Hood River than in big cities, but he’s afraid if rural communities don’t act now to reduce the ever-expanding impact of lighting at night, the beauty and majesty of the Milky Way will fade from view.

Generations will be left without an opportunity to be inspired by the stars.

Hendricks started a local advocacy group, DarkSky Gorge, to raise awareness, and is encouraged by the 85 members so far.

“I joined in this effort because I love the dark sky at night, it’s really nothing more complicated than that. I’m lucky enough to have a view of the sky from our deck and when you look at it, you understand your place in the universe,” says Hendricks.

How lights impact wildlife

It turns out light pollution causes more problems than just having a negative impact on viewing the night skies.

Scientists have amassed a body of research showing that unintended consequences of Artificial Light At Night (ALAN) is creating a host of environmental problems.

Michael McKeag. Photo: Michael McKeag

These include interfering with bird migrations, significant decreases in insect populations, changes in nocturnal animal behavior and sleep patterns, throwing normal predation/prey relationships into imbalance, decreasing nighttime pollination processes, disrupting aquatic populations and even changing the foliage cycles for trees.

“My colleague, John Barantine at DarkSky International, has compiled a database of more than 5,000 papers on ALAN research, and he produces a yearly summary of major findings,” says McKeag.

Humans aren’t immune to changes in the nighttime sky.

Extra exposure to light during what should be dark nighttime conditions can affect melatonin levels, important in many hormonal body functions.

And in a sort of ironic technological twist, modern LED lights, which account for energy savings, can produce a spectrum of light that has higher levels (than previous bulbs) of blue light, which is the normal color of daylight.

Studies show that exposure to blue light (420-440 nanometer wavelength) from LED bulbs can suppress melatonin production, interfering with natural sleep cycles and circadian rhythms in humans and animals.

Monitoring Gorge skies

Efforts to measure and document the nighttime sky conditions affected by light from cities, buildings, streetlights and other outdoor lighting sources are being led by groups like DarkSky International and their state chapters.

DarkSky International has an interest in returning the night sky to conditions that allow a clear view for all to see.

Today’s nighttime view is impacted by light domes that emanate from cities and can have an impact hundreds of miles away.

Stray light and light from upward facing fixtures can be reflected by clouds and interact with dust particles creating “skyglow.”

With the use of satellite data and monitoring stations on the ground, a picture of light pollution impact is being developed.

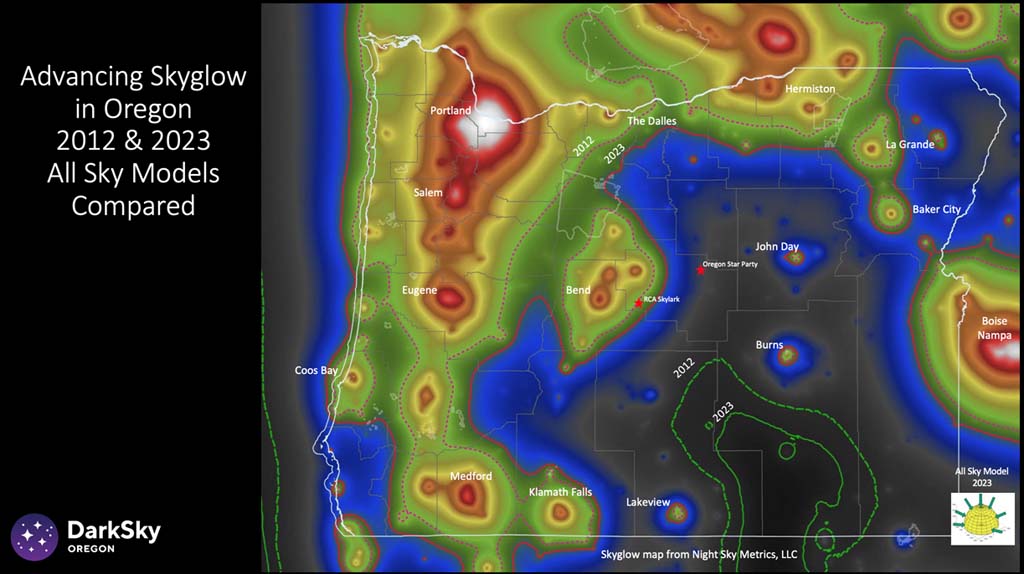

Comparison of the shift of the boundaries between light polluted and relatively pristine night sky between 2012 and 2023. Source: DarkSky Oregon

The DarkSky Oregon Chapter has been collecting, analyzing and charting light pollution data for at least five years.

Since 2019, DarkSky Oregon co-founder Bill Kowalik and McKeag have worked on the chapter’s Sky Quality Meter Program. An estimated 10 million data points have been collected pertaining to overall night brightness for 53 locations in Oregon.

By combining remote sensing information from satellites and data from a network of Sky Quality Meters, McKeag and colleagues were able to summarize measurements from 2012 to 2020, showing a 30% increase in “uplight” in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

McKeag says at least three years of data is needed to measure a statistically significant trend among Gorge communities.

“At the top of the list [for artificial light at night] is The Dalles, and second is Hood River,” says McKeag.

More data will be collected in 2024.

“DarkSky Oregon will be extending our statewide network of night sky monitoring stations to include sites at intervals the length of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, with installations starting this year,” says McKeag.

Promoting dark skies

In past years, McKeag has worked with the city of Mosier to get a Dark Sky Community Certification, presented his Sky Quality Meter data to the Gorge Climate Action Network and spoken with staff from the Gorge Commission (in charge of overseeing policies for the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area) about sky-quality data.

“There was interest from the Gorge Commission to look at the sky-quality data as it pertains to Key Viewing Areas, and the commission admitted that they didn’t really think about how the KVA would look at night,” says McKeag.

Seeing stars: Michael McKeag (bottom right) uses a laser pointer during a night-sky presentation in Hood River, Ore. Photo: Jurgen Hess

McKeag visited with staff at Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood in order to get the facility to turn off the ski slope lights during a Rose City Astronomy stargazing event.

“It was a chore for them to even try and figure out how to turn them off, but they did it, and people got to experience the transition of what you could observe in the sky when the lights went out. It was educational on how different it was,” he says.

McKeag says Travel Oregon is vigorously promoting dark sky tourism in rural areas.

“One of the resources they have is dark skies, and they could even be darker if they made changes to their outdoor lighting,” he says. “Urbanites are aware of the rewards, and they’re willing to travel and spend money when they do.”

Changing lighting codes

An additional byproduct of light pollution is wasted energy.

DarkSky organizations say one-third of all outdoor lighting is useless because the light is not directed at the right place. It’s common to have too much light switched on for an intended purpose—the use of dimmers and timers could result in significant savings.

The group calculates that the planet became 9% brighter at night from 2012-19.

That’s a good reason to urge the City of Hood River to take a look at adopting Dark Sky outdoor lighting requirements, says Mike Hendricks.

Mike Hendricks. Photo: Mike Hendricks

He points to the recent adoption of outdoor lighting codes by the city of Sisters, Ore., which incorporates Dark Sky lighting recommendations and has a five-year timeline for getting all public and private outdoor lighting up to DarkSky codes.

The codes allow temporary lights for holiday decorating and provide exemptions for security purposes, but eliminate upward-pointing light fixtures, searchlights and laser-light devices that extend past property boundaries.

“Right now, our codes in Hood River don’t really address outdoor lighting,” says Hendricks. “I’ve been having talks with our city planner and they have a copy of the recent outdoor lighting code [adopted in Sisters].”

“We’ve even approached the Hood River-White Salmon Bridge Authority, and particularly its Bridge Aesthetics Committee, on lighting for the new bridge, and from recent public meetings their aesthetics committee has incorporated some of our Dark Sky lighting language into account. It will be interesting to see their report, which is due in coming weeks.”

McKeag is an avid photographer and is involved with regional astronomy clubs that rely on dark skies for star parties and other community outreach events.

“I’ve taken long-exposure photographs from the Dalles Mountain looking across the light pollution from The Dalles and you can see the light dome of Portland,” says McKeag. “It’s so large, you can see it from central Oregon. In fact, I was just looking at a photograph that a person had taken from the south rim of Crater Lake looking across Wizard Island. Looking to the northeast you can see a conspicuous yellow blob on the horizon.”

He believes communities can work together to make dark skies a reality for the Gorge.

“Light pollution isn’t stored in the atmosphere or water or soil, so it really is the easiest form of pollution to address. It’s really just the flick of a switch, and it’s getting people to stop and think about it,” says McKeag. “We’re making arguments against light pollution based on evidence, not just opinion, and we’re trying to provide people with the firsthand experience of a dark sky, hoping to turn them into advocates. In turn they should tell their public officials that Dark Sky policies are a good idea.”