Pacific Northwest Tribes are at the forefront of leadership efforts to combat the effects of a warming environment

Scene saver: Tribal leaders are looking for innovative ways to protect the Nez Perce Indian Reservation, 750,000 acres with headquarters in Lapwai, Idaho, from the ravages of climate change. Photo: Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail Experience

By K.C. Mehaffey. October 3, 2024. It seemed like such a long shot. The Environmental Protection Agency had a lot of money on the table—$4.3 billion—for just 25 projects nationwide that would reduce pollution, advance environmental justice and curb greenhouse gas emissions.

The Nez Perce Tribe—with roughly 3,500 enrolled citizens and a 770,000-acre reservation—was competing against large state agencies and major cities and counties across the country, including Washington’s King County, where Seattle is located.

But in July, the Tribe’s comprehensive plan to move away from fossil fuels while improving the lives of its most vulnerable residents and making their reservation a safer place earned them a $37.3 million grant, followed in September by another $8.7 million grant.

To Stefanie Krantz, climate change coordinator for the Nez Perce Tribe, it feels like winning the lottery. Twice.

This fall, the Tribe—which calls itself the Nimíipuu—will embark on a five-year journey to reduce its own greenhouse gas emissions, restore its forests and build a better future for tribal members.

“It’s one of the largest grants we’ve ever received. It might be the largest,” Krantz tells Columbia Insight.

She says the combined $46 million will go a long way toward lifting people on the Nez Perce Reservation out of poverty, making it a safer place to be during wildfires and winter storms, and helping the Tribe become more resilient to the challenges that climate change has already brought to north-central Idaho and the 19,500 people who live on the reservation.

Plans are in place to begin conducting energy audits on inefficient residences and government buildings, replacing the tribal government’s gas-powered vehicles with electric ones, planting hundreds of thousands of trees and installing large solar arrays with battery packs so the Tribe can generate more of its own electricity.

The solar production will have the added benefit of reducing the amount of power the reservation gets from hydroelectric dams, which aligns with the Tribe’s goal of removing the four lower Snake River dams due to their impact on salmon, steelhead and other aquatic life.

Having their own power source is also a safety issue and an affordability issue, Krantz says. “We’re at the end of the grid. The power’s not reliable, and it costs a lot,” she says.

Many tribal households pay between $300 and $800 a month for electricity, she says.

“A lot of people use electricity to pump water, and during forest fires when everything’s on fire, the power is shut down and people can’t pump water. And in a lot of situations, they can’t leave. There’s nowhere to go that’s safe. The roads are forested … so the safest thing for people to do is shelter in place,” says Krantz.

Installing solar with batteries will enable people run air conditions, pump water to fight fires and power cell phones when the power lines are down. One of the solar arrays will be at the Clearwater River Casino, which will give the Tribe an emergency evacuation center. Other installations will be located at two tribal fisheries offices. [A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the Tribe would have solar installations at a tribal hatchery. —Editor]

“It’s going to make a big difference in people’s day-to-day lives. We can’t wait,” says Krantz. “We want to be an example to everyone else—to every other community that’s trying to stop hurting our climate and all our relations—the fish, the wildlife, native plants, pollinators and our people.”

“Yes, this is an emergency.”

Krantz says that the impacts of climate change are already evident on the Nez Perce Reservation.

In July, Lapwai, Idaho, sweltered through 20 consecutive days of temperatures over 99 degrees. Three years earlier—in June 2021—it experienced a record-breaking heat wave, with temperatures reaching 117 degrees. Within days, wildfires exploded, people evacuated and homes were destroyed.

Some Nez Perce tribal members died in that heat wave, along with wildlife and people’s horses, livestock and pets.

Salmon also struggle in extreme heat.

Stefanie Krantz. Photo: University of Idaho

“It’s hard for fish to get to Idaho because they’re ducking into cold-water refugia on their way up and then starving instead of coming up here to lay eggs,” Krantz explained at a July webinar on drought hosted by the National Integrated Drought Information System.

According to the Tribe’s climate action plan, “Catastrophic climate change is upon us and threatens the lands, waters and species the Tribe depends upon. … The Nez Perce Tribe is experiencing increasing severity and frequency of wildfires, drought, heatwaves, extreme precipitation, floods and erosion. This cycle of extremes has impacted the health, well-being and lifeways of the Nimíipuu in tangible and intangible ways.”

Krantz says wildfires have become one of their biggest problems.

Drought conditions caused by extreme heat makes tribal lands prone to massive fires.

Those fires are often followed by floods and landslides because there are no trees or shrubs left to hold the soil in place when it rains.

The landslides sometimes take out major infrastructure, such as roads. When land slides into a river or creek, sediments smother redds—the nests of salmon eggs that salmon lay in rivers and streams.

On the day of the webinar, Krantz described a reservation in the throes of such an emergency.

“The creeks are flooding, the roads are down, stuff is on fire and people are scrambling this morning to take care of that,” she said.

Krantz tells Columbia Insight that 34 homes and a vineyard on the reservation burned in wildfires this summer.

“I know how horrible this is, and what is at stake,” she says of climate change impacts. “Yes, this is an emergency. We have to do something about it right away. But it is totally doable.”

Effort pays off

The Nimíipuu have been working to curb the impacts of climate change for decades.

According to the Tribe’s web page on its climate program, the Tribe developed a carbon offset project in the mid-1990s, and its fisheries department began working on a project in 2005 to end water diversions from creeks and rivers on the reservation to keep water cooler and protect habitat for salmon and other species.

Then, in 2015, extremely low river flows and high summer temperatures made the lower Columbia River lethal for salmon in July—the height of adult sockeye migrations. In a year of high sockeye returns, a quarter million of them died in the lower river, including endangered Snake River sockeye bound for Idaho.

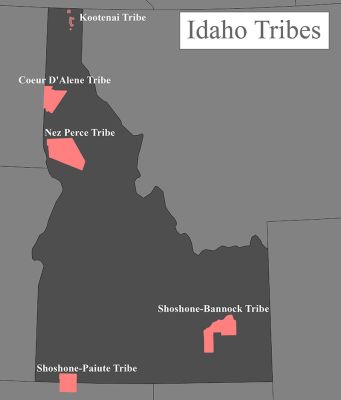

Idaho is home to five federally recognized Tribes. Map: EPA

Also in 2015, the Nez Perce Tribe experienced major wildfires.

Tribal leaders convened a climate change task force. In December 2016, Krantz was hired to become the Tribe’s first climate change coordinator.

She moved to Idaho from Monterey, Calif., to become first person in the state of Idaho to hold that title.

Krantz began meeting with tribal managers and staff to find ways to incorporate climate adaptation measures into their programs.

“I started working on a vulnerability assessment, and we quickly started to realize just how at-risk the tribe was,” she recalls, noting that the Nez Perce Reservation is among the highest fire-risk communities in the United States.

“Then Biden was elected, and the administration started putting real money toward climate change,” says Krantz.

She knew the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act would bring the possibility of new funding sources, so she kept her eyes out for grants. The EPA eventually offered Climate Reduction Pollution Grants to any applicants, and a second round of funding aimed at U.S. tribes.

The application process was lengthy.

“I actually pulled a few all-nighters, and other people did too. There were tears—lots of tears and some burnout,” she recalls of the weeks leading up to the application deadline.

Deep down, she feared that—despite all their work—the Tribe’s chances of being awarded a grant were slim.

In July, the EPA announced the 25 recipients of its Climate Pollution Reduction Grants program “to implement ambitious local and regional climate pollution reduction measures to significantly reduce greenhouse gasses (GHGs) by 2030 and beyond.”

The Nez Perce Tribe was the only Tribe to be awarded a grant in this phase of funding.

Then, in September, the EPA awarded another $300 million to 34 U.S. tribes, including another grant for the Nez Perce Tribe.

The Nisqually Indian Tribe and the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe in Washington were the other Tribes in the Pacific Northwest to win grants.

How money will be spent

One of the first things the Nimíipuu will do with the money is conduct energy audits on about 650 homes and three tribal facilities on the Nez Perce Reservation.

Over the next five years, they’ll complete the upgrades needed to make the homes energy efficient. Such improvements could include insulating and weatherproofing, replacing windows and doors and installing energy-efficient heating and cooling systems, like heat pump mini-splits.

“We have a lot of tribal members who are vulnerable, and they don’t have air-conditioning,” says Krantz.

While north-central Idaho has always gotten hot in the summer, Krantz notes that in the past, it didn’t get as hot, heat waves didn’t last as long and people could usually find relief at night or in the cool rivers and streams nearby.

She says with higher nighttime temperatures and harmful algal blooms making swimming holes unusable, cooling systems are necessary.

By ensuring that homes where elders or people with disabilities live are safe and cool, neighbors and the people who check on them will also benefit from having a place to go in emergency situations.

“It’s not enough to just stop burning fossil fuels.”

Funds will also be used to replace old wood stoves with new, EPA-approved stoves in 350 homes to improve the local air quality.

That’s just the beginning. According to the EPA announcements, the grants will also:

-Build multiple solar arrays with batteries to improve power reliability and increase safety during emergencies. The solar power will also reduce the Tribe’s reliance on fossil fuels and hydropower, which impact salmon

-Install 72 electric vehicle chargers and replace the Tribe’s vehicle fleet with electric vehicles

-Plant about 380,000 trees on 2,137 acres of land to sequester carbon, protect wildlife habitat, shade streams and improve fish habitat

Together, the work is estimated to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the equivalent of 18,700 metric tons by 2030. That’s like taking 4,451 gas-powered cars off the road.

By 2050, greenhouse gases will be reduced by 287,000 metric tons—the same as getting rid of 68,307 cars. It’s also more than a third but not quite half of the 670,575 metric tons of CO2-equivalent emissions currently emitted by all sectors on the reservation, including emissions from transportation, industries, electric use, commercial and residential buildings, agriculture and forest fires, the Tribe’s action plan shows.

Can one small Tribe make a difference?

Krantz—who is not a member of the Nez Perce Tribe—said she and other tribal staff put in lots of work to apply for the grant, but ultimately it was the Tribe’s leadership that made it possible to win the grants.

The Tribe, she says, is determined to separate itself from fossil fuels and hydropower, and become more resilient to the changes that a warming climate is bringing.

“We know it’s not enough to just stop burning fossil fuels,” says Krantz.

She says the tribe has made significant progress already—and more needs to be done—to restore natural habitats and soil health and ensure that the carbon-sequestering forests, wetlands and floodplains are functioning.

Eliminating fossil fuel emissions and restoring healthy ecosystems on the Nez Perce Reservation is a small part of the much larger work that needs to be done statewide, nationwide and worldwide, says Krantz.

But it could have a much larger impact.

“I think more than anything, our tribal leaders just want to walk the walk and show everyone this can be done,” she says.

Their message: “Let’s just do something. Let’s figure out how to make a difference and do everything that we can to get people inspired and willing to lead on climate.”

This is fantastic. Can’t wait to see the great work by NPT. Thank you for the coverage K.C. and Columbia Insight.

This is wonderful to see. Tribes across the country have come to the forefront of climate change response, and they are finally getting their due in funding support to prepare and protect their communities. There will be a lot of work ahead, and I wish the Nimiipuu the best in their efforts.

Thanks for a really interesting story. The Nimiipuu are uniquely positioned to show rural communities throughout the Northwest how they can meet the challenges of climate change. I hope this piece is picked up and republished by local papers throughout the region,