A dietary shift has led to a vitamin B1 deficiency in Pacific salmon. Researchers want to combat it

Be one: Chinook salmon are finding it increasingly difficult to live in harmony with their surroundings. Photo: OSU

By Kendra Chamberlain. January 9, 2024. Researchers at Oregon State University have discovered a freshwater source of the vitamin thiamine that may help give wild salmon populations a leg up against thiamine deficiency complex (TDC).

Wildlife around the world is suffering from a lack of thiamine. The vitamin, also known as B1, is a vital component to all cellular activity and consequently is incredibly important for all organisms on earth.

In Pacific salmon, California hatchery employees began noticing higher mortality rates in hatchery fry in early 2020.

Researchers determined the culprit was TDC, then linked the thiamine deficiencies to changes in salmon diet in the Pacific Ocean.

Christopher Suffridge, senior research associate in the Department of Microbiology in the OSU College of Science, and doctoral student Kelly Shannon, have found possible sources of thiamine in freshwater spawning grounds that may help boost thiamine levels in California’s wild chinook populations.

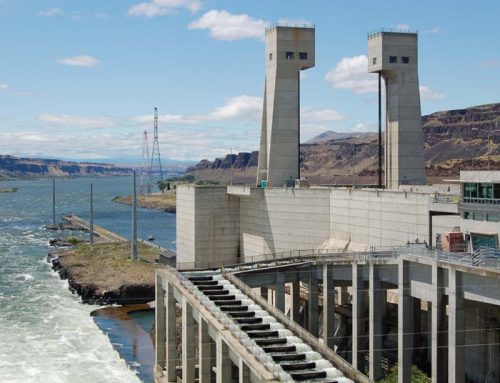

In the Sacramento River watershed, the team found increased prevalence of two families of bacteria in dammed rivers that has increased the availability of thiamine in areas where salmon spawn.

“Bacteria of these groups have been found in past studies to be associated with human impacts of rivers, such as the generation of reservoirs by the building of dams,” Shannon told Columbia Insight in an email. “Overall, this tells us there could be an ecological role at play since humans play a major role in structuring compositions of microbial communities, the bedrock of freshwater (and all global) food webs and thiamine availability, by how we change the flow and chemistry of rivers.”

Scientists don’t know why TDC has become so widespread among wildlife around the globe.

Thiamine deficiencies have been linked to population declines of several fish species, including trout in the Great Lakes and both Pacific and Atlantic salmon, as well as dozens of bird species, eel and mussels, and even moose.

Diet shift tied to climate change

Thiamine is produced by species of bacteria, fungi, plants and phytoplankton, and moves through the food web as predators catch and eat prey.

But some animals also have high levels of thiaminase, an enzyme that breaks down thiamine.

If an animal consumes too much thiaminase, the enzyme will begin breaking down its own thiamine stores.

That’s exactly what researchers think is happening to salmon populations in the Pacific, according to Suffridge.

Populations of chinook salmon from California are now consuming a much less diverse diet while out in the Pacific, relying mostly on anchovies.

“Anchovies are high in the enzyme thiaminase,” Suffridge told Columbia Insight in an email.

“The prevalence of anchovies in the marine feeding grounds for the chinook is likely driven by oceanographic shifts tied to climate change,” he added. “Normally the chinook’s diet is balanced between sardines, squid and anchovies.”

The consequences of that shift in diet are now becoming clear.

When females return to their freshwater spawning grounds and lay eggs, the thiamine deficiency is passed on to the eggs. And while hatchery salmon are now treated with thiamine baths to help combat TDC, the benefits of those baths are short lived if the salmon are being exposed to higher than normal levels of thiaminase while in the ocean.

The discovery of thiamine in freshwater spawning grounds is good news for salmon populations.

Suffridge described it as a “naturally occurring thiamine bath.” But the concentrations of thiamine found were still much lower than those given to fish in hatcheries.

It’s still unclear if these natural sources of thiamine are at high enough concentrations to “truly mitigate the symptoms of TDC,” said Shannon.