Proposed 11,500-acre Qapqápa Wildlife Area marks the first time Tribes might co-manage a wildlife area with Oregon

Preserved view: Framed by mountain mahogany, Beaver Creek flows through part of the proposed Qapqápa Wildlife Area in northeastern Oregon. Photo: Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

By Kendra Chamberlain. September 11, 2025. If everything goes as planned, members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) will soon be able to return to a land they haven’t had access to since 1855.

CTUIR and the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife are hoping to co-manage the proposed Qapqápa Wildlife Area, a roughly 11,500-acre tract of land linking the Umatilla and Walla Walla National Forests.

CTUIR and ODFW received a $22 million grant from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund to acquire the property and co-manage it as a wildlife area as part of the USDA’s State-Tribal Partnership Program.

The grant offers an opportunity to return land management of the area to its original stewards.

CTUIR is a confederation of three tribes of central Oregon: the Umatilla, the Walla Walla and the Cayuse. The proposed wildlife area is part of the land that was ceded by these three tribes in the Treaty of 1855.

“That land was the ancestral homeland of the tribes,” Anton Chiono, habitat conservation project manager, CTUIR Department of Natural Resources, tells Columbia Insight.

Qapqápa (pronounced cop-COP-a) means “place among the big cottonwoods” in the Sahaptian family of languages, which includes Umatilla and Walla Walla.

CTUIR and ODFW plan to manage the land for Tribal first foods, which includes salmon, deer, elk, root, berries and water.

The wildlife area will also offer public access for hunting and fishing.

The land, which is privately owned, includes stretches of the Grande Ronde River and Beaver Creek, offering important spawning and rearing habitat for threatened spring Chinook salmon, summer steelhead and bull trout, as well as traditional fishing spots for the Tribes.

Land rights and ownership

The Umatilla, Walla Walla and Cayuse tribes ranged throughout north-central and eastern Oregon and the Blue Mountains.

“Cayuse were horse people. They ranged around the Columbia Plateau a little bit more broadly,” says Chiono. “The Walla Walla and the Umatilla tribes themselves were largely river people, and so their seasonal migrations would be throughout that aboriginal title land area, up and down the rivers as the seasons came and went and various food items came and went.”

The tribes lost 6.4 million acres of land as a result of what’s known as the Walla Walla Treaty Council of 1855, in exchange for a small reservation in Pendleton, Ore.

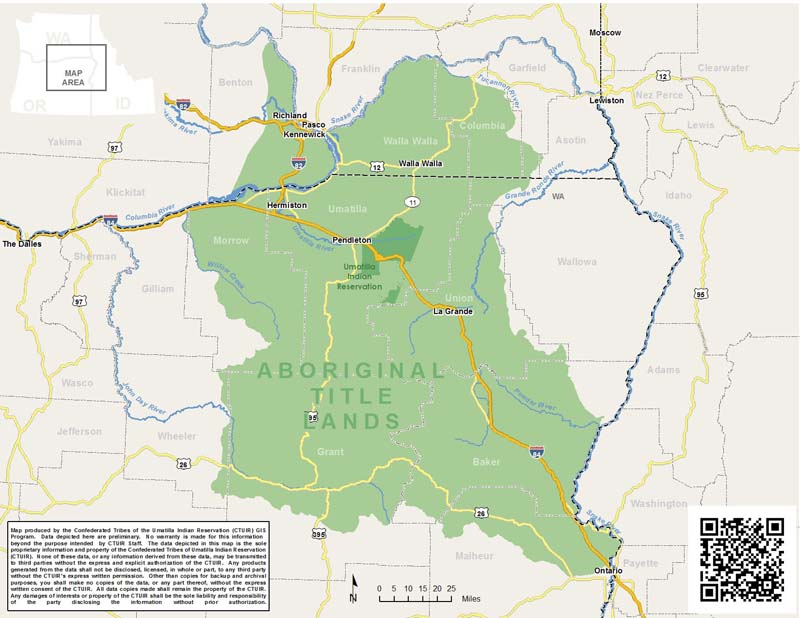

The Qapqápa Wildlife Area will be located in Oregon’s Union County. Map: CTUIR

While the Tribes retained rights to hunt, fish and gather food on ceded territories, those rights did not extend to private property.

“So anything that was subsequently settled no longer became available to the Tribes to exercise their reserve treaty rights,” says Chiono.

That includes the proposed Qapqápa Wildlife Area, located in Union County, Ore.

“The Confederated Tribes have done a lot of work over the years to try to catalog all these areas of cultural importance, and there are multiple ones on that property itself,” says Chiono. “It’s really neat history, really important history, and really, really exciting at the opportunity to reunite the tribes with such an important piece of land.”

Merlo involvement

The land is owned by the Harry A. Merlo Foundation, which took over the ranch after Merlo died in 2016. Merlo was a well-known timber baron and former CEO of Louisiana-Pacific, the wood building materials company known for bringing oriented strand board (OSB) to home construction.

Merlo purchased the 11,438-acre ranch and stewarded the land for wildlife habitat using grazing and timber management alongside conservation strategies.

“[The land] really is in incredible shape. And I think that’s a testament to Harry Merlo and his vision,” says Chiono. “I never had the opportunity to meet him, but from what I’ve learned of him, it was very important to demonstrate that you could be a responsible steward of the land and its natural resources, and also have a working landscape, which in a natural resource economy is very important to the rural West.”

New moon: The Qapqápa Wildlife Area will give Tribes and public access to traditional Indigenous hunting, fishing and foraging land. Photo: David Jensen/Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

The proposed wildlife area will include active forest management as well as habitat restoration and conservation projects.

“I think he truly believed that those things didn’t have to be mutually exclusive, and tried to demonstrate that on his property,” says Chiono.

The project would represent the first time the state has co-managed a wildlife area with Tribes.

The Tribal-State Partnership Program requires that the land be owned by the state but is co-managed by both governments.

Chiono says there’s lots of work to be done on what that co-management will look like on the ground.

“We’re largely charting a new course,” says Chiono. “So it’s kind of exciting that we are breaking new ground here. But it also means we don’t quite know what that looks like yet.

“And, of course, this is all contingent on getting the project across the finish line. It’s certainly not a done deal yet, but we, of course, are hopeful.”

CTUIR and ODFW are aiming to complete the acquisition in 2026, with the help of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, a hunting advocacy group based in Montana. The project will also need to be approved by the state’s Fish and Wildlife Commission.

This is great news!

Congratulations and thanks to all those involved in this conservation success story.

A testament to cooperation and vision. I truly believe tribes are the best stewards of the land.

Finally! We have taken indigenous people way too much! We need to allow the First Nations to feel at home again!

This is very good news but it’s only a small token compared to what was stolen from them.